All rights reserved.

PORTRAIT OF E. H. SHACKLETON

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY HUGH ROBERT MILL, D.Sc. AN ACCOUNT OF THE FIRST JOURNEY TO THE SOUTH MAGNETIC POLE BY PROFESSOR T. W. EDGEWORTH DAVID, F.R.S.

CHAPTER VIII. PROFESSOR DAVID'S NARRATIVE ( Continued )

The old dragon under ground

In straiter limits bound,

Not half so far casts his usurped sway,

And wroth to see his kingdom fail,

Swinges the scaly horror of his folded tail.

MILTON

IT had, of course, become clear to us before this letter was written, in view of our experience of the already cracking sea ice near the true Granite Harbour, as well as in view of our comparatively slow progress by relay, that our retreat back to camp from the direction of the Magnetic Pole would in all probability be entirely cut off through the breaking up of the sea ice. Under these circumstances we determined to take the risk of the Nimrod arriving safely on her return voyage at Cape Royds, where she would receive the instructions to search for us along the western coast, and also the risk of her not being able to find our depot and ourselves at the low sloping shore. We knew that there was a certain amount of danger in adopting this course, but we felt that we had got on so far with the work entrusted to us by our Commander, that we could not honourably now turn back. Under these circumstances we each wrote farewell letters to those who were nearest and dearest, and the following morning, November 2, we were up at 4.30 a.m. After putting all the letters into one of our empty dried-milk tins, and fitting on the air-tight lid, I walked with it to the island and climbed up to the cairn. Here, after carefully depoting several bags of geological specimens at the base of the flagstaff, I lashed the little post office by means of cord and copper wire securely to the flagstaff, and then carried some large slabs of exfoliated granite to the cairn, and built them up on the leeward side of it in order to strengthen it against the southerly blizzards. A keen wind was blowing, as was usual in the early morning, off the high plateau, and one's hands got frequently frost-bitten in the work of securing the tin to the flagstaff. The cairn was at the seaward end of a sheer cliff two hundred feet high.

On returning to camp I put some chopped seal meat into the cooking-pot on our blubber stove, which Mawson had meanwhile lighted, and about three-quarters of an hour later we partook of some nourishing, but no less indigestible seal bouillon. It was later than usual when we started our sledges, and the pulling proved extremely heavy. The sun's heat was thawing the snow surface and making it extremely sticky. Our progress was so painfully slow that we decided, after, with great efforts, doing two miles, to camp, have our hoosh, and then turn in for six hours, having meanwhile started the blubber lamp. At the expiration of that time we intended to get out of our sleeping-bag, breakfast, and start sledging about midnight. We hoped that by adopting nocturnal habits of travelling, we would avoid the sticky ice-surface which by daytime formed such an obstacle to our progress.

We carried out this programme on the evening of November 2, and the morning of November 3. We found the experiment fairly successful, as at midnight and for a few hours afterwards, the temperature remained sufficiently low to keep the surface of the snow on the sea ice moderately crisp.

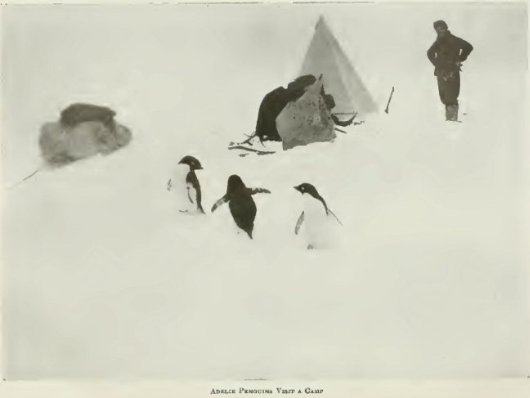

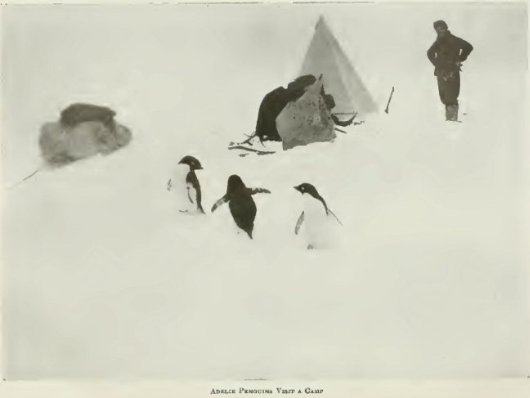

43. ADELIE PENGUINS VISIT A CAMP

44. SEALS AT THE ICE-EDGE

On November 3 and 4 the weather was fine, and we made fair progress. At noon Mawson cleaned out the refuse from our blubber lamp. Amongst this were a few dainty bits; Mackay was what he called "playing the skua", picking these over, when he accidentally transferred to his mouth and swallowed one of the salt wicks which we had been using in the blubber lamp. Mawson and I were unaware of this episode at the time. Later on, towards evening, he complained much of thirst, and proferred a gentle request, when the snow was being thawed down preparatory to making hoosh, that he might be allowed to drink some of the water before the hoosh was put into it; at the same time he gave us the plausible explanation above mentioned as the cause of his exceeding thirst. After debating the matter at some length, it was decided, in view of the special circumstances surrounding the case, and without creating a precedentwhich otherwise might become a dangerous onethat he might be allowed on this occasion to take a drink. Mackay, however, considered that this water gift was given grudgingly, and of necessity, and accordingly he sternly refused to accept it. Just then, the whole discussion was abruptly terminated through the pot being accidentally capsized when being lifted off the blubber lamp, and the whole of the water was lost.

On the following day, November 5, we were opposite a very interesting coastal panorama, which we thought belonged to Granite Harbour, but which was really over twenty miles to the north of it.]Magnificent ranges of mountains, steep slopes free from snow and ice, stretched far to the north and far to the south of us, and finished away inland, towards the heads of long glacier cut valleys, in a vast upland snow plateau. The rocks which were exposed to view in the lower part of these ranges were mostly of warm sepia brown to terra cotta lint, and were evidently built up of a continuation of the gneissic rocks and red granites which we had previously seen. Above these crystalline rocks came a belt of greenish-grey rock, apparently belonging to some stratified formation and possibly many hundreds of feet in thickness; the latter was capped with a black rock that seemed to be either a basic plateau lava, or a huge sill. In the direction of the glacier valleys, the plateau was broken up into a vast number of conical hills of various shapes and heights, all showing evidence of intense glacial action in the past. The hills were here separated from the coast-line by a continuous belt of piedmont glacier ice. This last terminated where it joined the sea ice in a steep slope, or low cliff, and in places was very much crevassed. Mawson at our noon halts for lunch, continued taking the angles of all these ranges and valleys with our theodolite.

The temperature was now rising, being as high as 22 Fahr. at noon on November 5. We had a very heavy sledging surface that day, there being much consolidated brash ice, sastrugi, pie-crust snow, and numerous cracks in the sea ice. As an offset to these troubles we had that night, for the first time, the use of our new frying-pan, constructed by Mawson out of one of our empty paraffin tins. This tin had been cut in half down the middle parallel to its broad surfaces, and loops of iron wire being added, it was possible to suspend it inside the empty biscuit tin above the wicks of our blubber lamp. We found that in this frying-pan we could rapidly render down the seal blubber into oil, and as soon as the oil boiled we dropped into the pan small slices of seal liver or seal meat. The liver took about ten minutes to cook in the boiling oil, the seal meat about twenty minutes. These facts were ascertained by the empirical method. Mawson discovered by the same method that the nicely browned and crisp residue from the seal blubber, after the oil in it had become rendered down, was good eating, and had a fine nutty flavour. We also found, as the result of later experiments, that dropping a little seal's blood into the boiling oil produced eventually a gravy of very fine flavour. If the seal blood was poured in rapidly into the boiling oil, it made a kind of gravy pancake, which we also considered very good as a variety.