To those who protect the

Shackleton heritage at Cape Royds

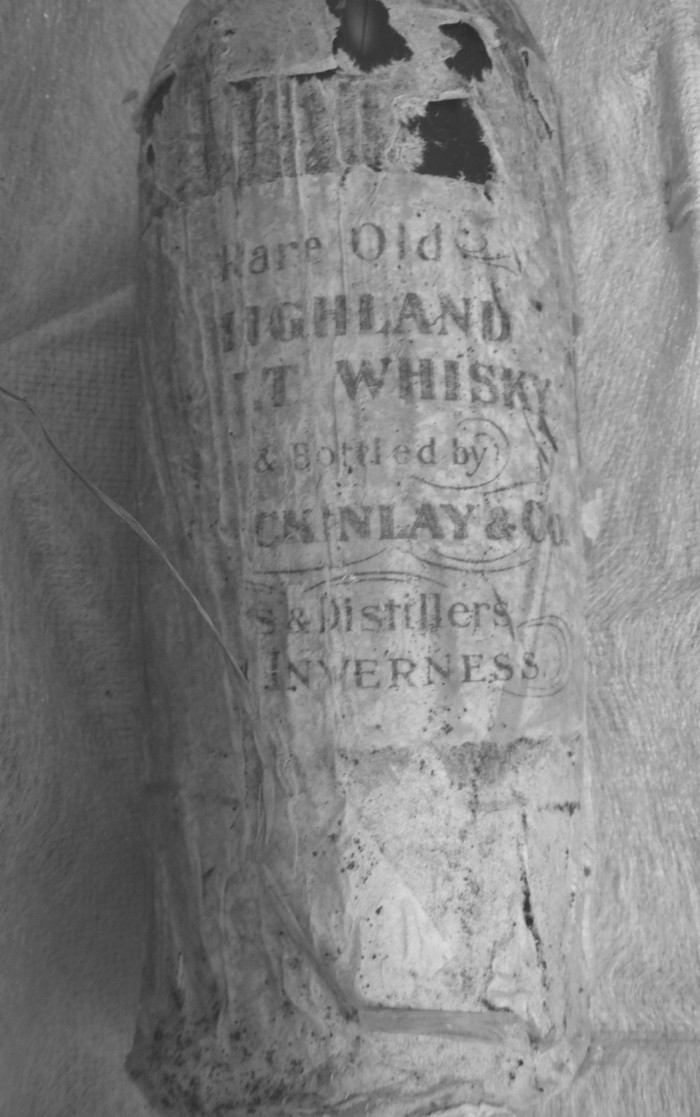

Sir Ernest Shackleton could never have imagined his name being closely associated with whisky, certainly not in the title of a book. Rarely did he consume strong drink. On his expeditions, he tolerated a mild spree at times of celebration. But that was all. Drinking to excess appalled him. From an early age, growing up in a teetotal home, he was leery of alcohol. How, then, did he feel about signing an order for 25 cases of whisky 300 bottles for his 190709 British Antarctic Expedition?

This book follows the circular story of the Rare Old Highland Malt Whisky taken south on his Nimrod expedition. It celebrates the extraordinary achievements of men exploring an extraordinary place. It dips into the human-interest stories of polar life in the heroic era of Antarctic exploration. At times, the view is up-close and personal. Shackleton once wrote of his interest in documenting the little incidents that go to make up the sum of the days work, the humour and the weariness, the inside view of men on an expedition. Here is one such account, based largely on what he wrote and said about the expedition and also on what the members of his expedition wrote, for most participants kept a diary or journal.

Shackletons world fame is founded on the Endurance expedition of 191417, an attempt to cross the Antarctic continent that was foiled by the crushing of the ship in pack ice. The heroics that followed ensured Shackleton and his men would have a place forever in the annals of polar history and world exploration at large, even though they were a long way from setting foot on the continent. His Nimrod expedition, seven years earlier, targeted the South Pole from the opposite side of Antarctica, generating a public aura akin to a 1960s lunar landing. At Cape Royds in the McMurdo Sound region stands the only tangible evidence of Shackleton in Antarctica: his hut, under which, until recently, lay a long-kept secret.

Antarctic exploration and whisky, in their own way, are both steeped in history, maturity, endurance, character, and edgy technology. Both have a worldwide following, millions of fans. Their pathways coincided on the British Antarctic Expedition 190709. With the recovery 100 years later of three cases of Scotch from icy entombment under the hut at Cape Royds and the subsequent return of three bottles to Scotland for sampling, analysis and a near-magical replication, the relationship of whisky and Antarctic exploration came sharply into focus. All of which makes for a unique odyssey to the end of the Earth and back.

Neville Peat, Broad Bay, Dunedin, New Zealand, August 2012

On a sunlit gem of a day that is cold enough to form rime ice on a beard, diamond dust is something to marvel at. It occurs when sunshine bounces off crystals of water vapour suspended in the air. A sparkling fairyland effect is the result. In Antarctica, watch out, too, for other tricks of light and atmosphere. Mock suns in summer, lunar haloes in winter and mirages for much of the year. Two peaks where only one is mapped. Islands elevated. Penguins that appear suspended in mid-air.

Yet water vapour is not an obvious feature when you visit Ross Island, McMurdo Sound. Here it never rains and rarely snows. Blizzards are filled with dry powder snow blown from elsewhere, and in the sunless depths of winter the air may be cold enough to crack metal.

The day I fly to Cape Royds, Ross Island an address straight out of the heroic era of Antarctic exploration summer is full blown. Virtually cloudless, blindingly bright, uncommonly still. It is early January 2007.

With temperatures near zero, or even a bit above that, the day is too warm for diamond dust. Nonetheless, a fine day in the McMurdo Sound region is a glittering sensation. Look around.

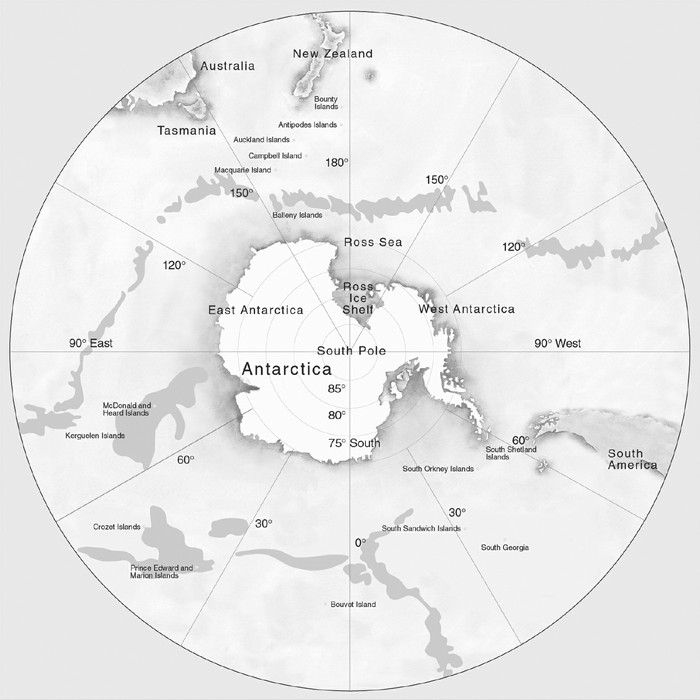

Mount Erebus is the great hulking centrepiece of Ross Island, its summit often generating a plume of pale blue smoke and steam. But not this day. Is there a lid on it? In the astonishingly clear air, any thought that this could be an active volcano reaching a breathtaking 3794 metres higher than Aoraki Mount Cook in New Zealand and topped by a lake of boiling lava seems preposterous. Scale is deceptive. Forty kilometres away? Surely not. From Scott Base at the foot of elongate Hut Point Peninsula, which forms Ross Islands southern tip, Erebus looks like a large local hill, an easy climb.

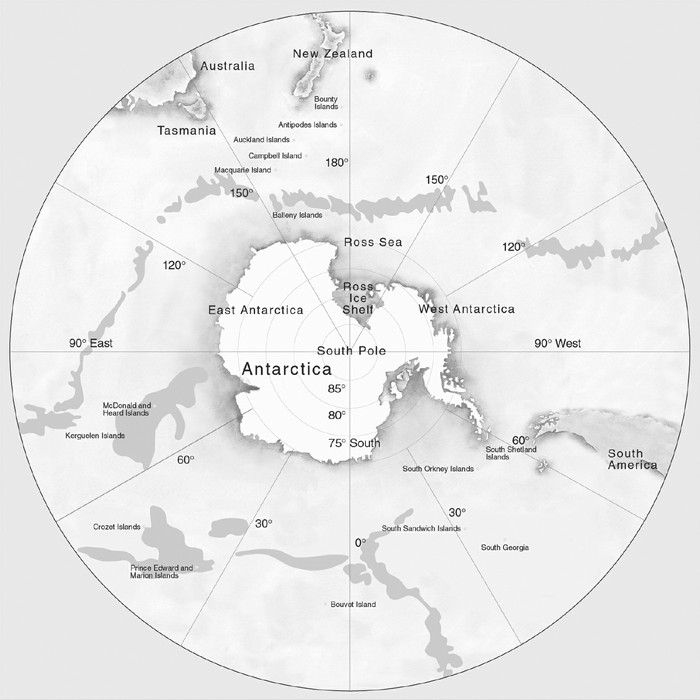

To the south and east lies the enormous white flatness of the Ross Ice Shelf, the Barrier to the South Pole for the heroic-era explorers from Britain who came here. Picture a creeping wall of ice 80 to 100 metres thick and as large as France shouldering a volcanic doorstop, Ross Island. Something has to give. The leading edge of the great wall is crumpled into radiating waves and steep pressure ridges, metres high.

To the southwest, the Royal Society Range stands stately, Mount Lister the tallest of its peaks, topping 4000 metres. On the western flank of McMurdo Sound, lying behind a skirt of piedmont ice, are the Dry Valleys. Three sprawling valley systems here comprise the greatest expanse of bare rock in all of Antarctica.

At McMurdo Sound, therefore, natures forces have put together an unbelievably diverse and dynamic array of landforms and ice features, concentrated on the worlds southernmost port for shipping, the leaping-off place to the South Pole by air or overland.

My weeks assignment in January 2007 coincides with the breakout of sea ice in McMurdo Sound. Sea ice comes and goes in an annual cycle, forming through winter and spring to a thickness of about two metres. No two years are quite the same, and generally ice-breakers have round-the-clock work to do at Christmas and New Year, cutting a channel for cargo and fuel ships directly to the ice wharf at McMurdo Station, the American base.

As it was for explorers Scott and Shackleton in the early years of the 20th century, the sea ice is a critical factor for modern expeditions, which depend on a pattern of summer sunshine and periodic gales to weaken and disperse it. The ships of the two eras might be worlds apart in design, manufacture and kit. But here, natural forces will be nothing less than formidable.

When I take to the air from Scott Base with New Zealand helicopter pilot Rob McPhail, McMurdos sea ice beyond Hut Point Peninsula is revealed as a seamless extension of the ice shelf. White, relentlessly white, bordering on painfully so.

The blunt-nosed Iroquois continues climbing. I have an altitude in mind whatever it takes for a view of both Antarctic bases, Scott and McMurdo. In my experience of this region, going back 30 years, I have never seen an oblique photograph of the two stations in their volcanic landscape. Separated by a hilly three kilometres, the stations, built near sea level, are obscured from each other. My commission is to produce a book celebrating 50 years cooperation between New Zealand and the United States in Antarctica, and the least I can do is try to illustrate the proximity of the stations.