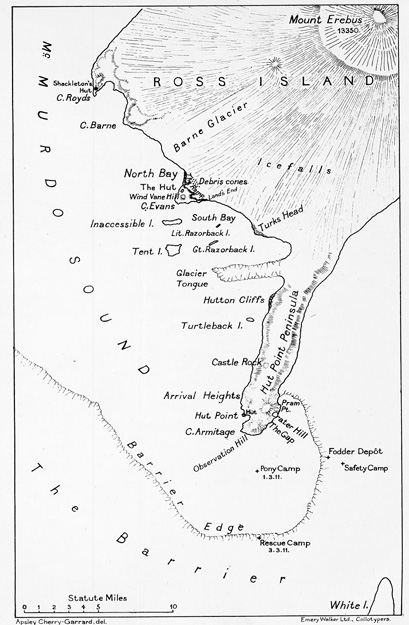

Ross Island map showing winter quarters for the Discovery, Nimrod, and Terra Nova expeditions, from Apsley Cherry-Garrards Worst Journey in the World (New York, 1922).

AN EMPIRE OF ICE

Also by Edward J. Larson

A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800,

Americas First Presidential Campaign (2007)

The Creation-Evolution Debate: Historical Perspectives (2007)

The Constitutional Convention: A Narrative History from the

Notes of James Madison (with Michael Winship) (2005)

Evolution: The Remarkable History of a Scientific Theory (2004)

Evolutions Workshop: God and Science on the Galapagos Islands (2001)

Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and Americas Continuing Debate

Over Science and Religion (1997)

Sex, Race, and Science: Eugenics in the Deep South (1995)

Trial and Error: The American Controversy Over Creation and Evolution (1985)

AN EMPIRE OF ICE

Scott, Shackleton, and the Heroic Age of Antarctic Science

EDWARD J. LARSON

Copyright 2011 by Edward J. Larson.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

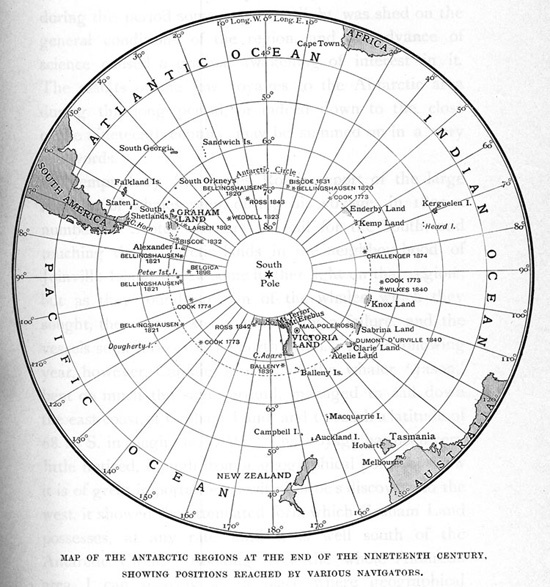

Plates 5 and 23 courtesy of Scott Polar Research Institute Archives. Maps, figures, and plates from Robert Scott, The Voyage of the Discovery (New York, 1905), Roald Amundsen, The South Pole (New York, 1922), and James Ross, A Voyage of Discovery and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions (London, 1847), courtesy of the University of Georgia Libraries.

Maps, figures, and plates from Ernest Shackleton, The Heart of the Antarctic (Philadelphia, 1909), and Apsley Cherry-Gerrard, The Worst Journey in the World (New York, 1922), courtesy of UCLA Libraries. Maps, figures, and plates from R. F. Scott, Scotts Last Expedition (New York, 1913), courtesy of Pepperdine University Libraries.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Designed by James J. Johnson and set in Monotype Dante type by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Larson, Edward J. (Edward John)

An empire of ice : Scott, Shackleton, and the heroic age of Antarctic science / Edward J. Larson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-15408-5 (clothbound : alk. paper) 1. AntarcticaDiscovery and explorationBritish. 2. Scientific expeditionsAntarcticaHistory20th century. 3. Scott, Robert Falcon, 18681912. 4. Shackleton, Ernest Henry, Sir, 18741922. I. Title.

G872.B8L37 2011

919.89dc22

2010044396

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

IN THE SPIRIT OF

Robert Falcon Scott,

who wrote to his wife from his final camp on the Polar Sledge Journey

about their young son,

Make the boy interested in natural history, if you can;

I dedicate this book to our son,

Luke Anders Larson,

who has expressed interest in all things Antarctic

CONTENTS

Antarctic map showing what was known in 1900, before the Discovery expedition, including coastlines and the dates and places of prior expeditions, from Robert Scotts Voyage of the Discovery (New York, 1905).

PREFACE

WHEN I TELL FRIENDS THAT IM WRITING A book about the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration, they typically respond in one of two ways. Some say how much they admire Ernest Shackletons leadership style, while others question Robert Scotts tactics in trying to reach the South Pole first. Both responses are telling. A century after their exploits, these two men are still widely known for their personal achievements, but their fame rests largely on how they dealt with adversity in their efforts to reach the geographical South Pole. That, most people assume, is why they went to Antarctica; much else about their expeditions is forgotten.

This book is neither a paean to Shackletons leadership nor a critique of Scotts choices. It is about what was central to British efforts in the Antarctic. In the era before World War I, when Antarctic exploration was largely a British project, that project was largely concerned with science.

Scott led two expeditions to Antarctica during the first twelve years of the twentieth century; Shackleton led one. Scotts first was part of an international program also involving German and Swedish teams to explore the Antarctic that was fundamentally scientific in design and execution, although of course it had military, commercial, ideological, and personal motives as well. The ensuing expeditions by Shackleton and Scott followed directly on Scotts first effort and adopted its basic scheme. All three British expeditions entered Antarctica through the Ross Sea. They form a logical unit that stand apart from other expeditions of the so-called Heroic Age, including Shackletons second, both in their organization and in their impact.

If the race to the South Pole eventually consumed Scott, it was never at the expense of science. His two expeditions and Shackletons 19079 venture carried enormous scientific baggage. If getting to the pole first was Scotts overriding objective, he went about it the wrong way. If he meant to get to the pole first while doing meaningful science along the way, he did it rightbut in doing so, he fatally handicapped himself in a contest against Roald Amundsen, a polar adventurer of proven ability who cared only about winning the race. Focus empowered him. Scott and Shackleton served many masters, one of which was the British conception of scientific discovery, exploration, and conquest.

Any account of the three British Antarctic expeditions between 1901 and 1913 inevitably touches on Shackletons leadership, Scotts choices, and the race to the pole. But these expeditions were complex enterprises. Science wove through every part of them, both influencing and being influenced by their other aspectsincluding such critical intangibles as leadership and choices. I know of no better way to understand the whole of these expeditions than through the lens of their research. Fortunately, the less-told tale of the explorers scientific activities is often as gripping as the story of their polar quest.

Examining the astounding research efforts of these expeditions also illumines the fundamental place of science in Victorian and Edwardian British culture. Britain built and sustained its global empire during this period. In doing so, explorers and imperial officers took Western science to the four corners of the worldmeasuring, mapping, and collecting specimens as part of their program to subdue alien territory and make it British. The proud citizen of a nation that had recently cast off foreign rule, Amundsen came from a different tradition than Scott and Shackleton, and had different goals. Empire is not only about the physical conquest of territories; for the British, it was always about scientifically exploring and systematically exploiting them even as the definition and conception of science itself evolved. In a sense, then, this story is not only about the explorers science in its various and contested forms. It is also about power and politics; culture and commerce; hubris and heroism at the end of the Earth.