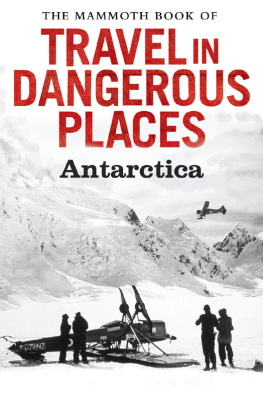

The Mammoth Book of

TRAVEL IN DANGEROUS PLACES PRESENTS

Antarctic

Edited by

John Keay

Constable & Robinson Ltd

5556 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2012

Collection and editorial copyright John Keay, 1993

Content published as The Robinson Book of Exploration (Robinson, 1993). Published as The Mammoth Book of Travel in Dangerous Places (Robinson, 2010).

Farthest South, Ernest Henry Shackleton.

Taken from The Heart of the Antarctic

(Heinemann, 1910)

The Pole at Last, Roald Amundsen.

Taken from The South Pole (John Murray, 1912)

In Extremis, Robert Falcon Scott.

Taken from Scotts Last Expedition

(Smith Elder & Co., 1913)

The right of John Keay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in

Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-47210-011-5 (ebook)

CONTENTS

Farthest South

Ernest Henry Shackleton

The Pole at Last

Roald Amundsen

In Extremis

Robert Falcon Scott

FARTHEST SOUTH

Ernest Henry Shackleton

(18741922)

Born in Ireland, Shackleton joined the merchant navy before being recruited for Captain Scotts 1901 expedition to Antarctica. He was with Scott on his first attempt to reach the South Pole and, though badly shaken by the experience, realized that success was now feasible. In 1907, with a devoted team but little official support, he launched his own expedition. A scientific programme gave it respectability but Shackleton was essentially an adventurer, beguiled alike by the challenge of the unknown and the reward of celebrity. His goal was the Pole, 90 degrees south, and by Christmas 1908 his four-man team were already at 85 degrees.

D ecember 25 Christmas Day. There has been from 45 to 48 of frost, drifting snow and a strong biting south wind, and such has been the order of the days march from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. up one of the steepest rises we have yet done, crevassed in places. Now, as I write, we are 9500 ft. above sea-level, and our latitude at 6 p.m. was 85 55 South. We started away after a good breakfast, and soon came to soft snow, through which our worn and torn sledge-runners dragged heavily. All morning we hauled along and at noon had done 5 miles 250 yards. Sights gave us latitude 85 51 South. We had lunch then, and I took a photograph of the camp with the Queens flag flying and also our tent flags, my companions being in the picture. It was very cold, the temperature being minus 16 Fahr., and the wind went through us. All the afternoon we worked steadily uphill, and we could see at 6 p.m. the new land plainly trending to the south-east. This land is very much glaciated. It is comparatively bare of snow, and there are well-defined glaciers on the side of the range, which seems to end up in the south-east with a large mountain like a keep. We have called it The Castle. Behind these the mountains have more gentle slopes and are more rounded. They seem to fall away to the south-east, so that, as we are going south, the angle opens and we will soon miss them. When we camped at 6 p.m. the wind was decreasing. It is hard to understand this soft snow with such a persistent wind, and I can only suppose that we have not yet reached the actual plateau level, and that the snow we are travelling over just now is on the slopes, blown down by the south and south-east wind. We had a splendid dinner. First came hoosh, consisting of pony ration boiled up with pemmican and some of our emergency Oxo and biscuit. Then in the cocoa water I boiled our little plum pudding, which a friend of Wilds had given him. This, with a drop of medical brandy, was a luxury which Lucullus himself might have envied; then came cocoa, and lastly cigars and a spoonful of creme de menthe sent us by a friend in Scotland. We are full to-night, and this is the last time we will be for many a long day. After dinner we discussed the situation, and we have decided to still further reduce our food. We have now nearly 500 miles, geographical, to do if we are to get to the Pole and back to the spot where we are at the present moment. We have one months food, but only three weeks biscuit, so we are going to make each weeks food last ten days. We will have one biscuit in the morning, three at mid-day, and two at night. It is the only thing to do. To-morrow we will throw away everything except the most absolute necessities. Already we are, as regards clothes, down to the limit, but we must trust to the old sledge-runners and dump the spare ones. One must risk this. We are very far away from all the world, and home thoughts have been much with us to-day, thoughts interrupted by pitching forward into a hidden crevasse more than once. Ah, well, we shall see all our own people when the work here is done. Marshall took our temperatures to-night. We are all two degrees sub normal, but as fit as can be. It is a fine open-air life and we are getting south.

December 26 Got away at 7 a.m. sharp, after dumping a lot of gear. We marched steadily all day except for lunch, and we have done 14 miles 480 yards on an uphill march, with soft snow at times and a bad wind. Ridge after ridge we met, and though the surface is better and harder in places, we feel very tired at the end of ten hours pulling. Our height to-night is 9590 ft. above sea-level according to the hypsometer. The ridges we meet with are almost similar in appearance. We see the sun shining on them in the distance, and then the rise begins very gradually. The snow gets soft, and the weight of the sledge becomes more marked. As we near the top the soft snow gives place to a hard surface, and on the summit of the ridge we find small crevasses. Every time we reach the top of a ridge we say to ourselves: Perhaps this is the last, but it never is the last; always there appears away ahead of us another ridge. I do not think that the land lies very far below the ice-sheet, for the crevasses on the summits of the ridges suggest that the sheet is moving over land at no great depth. It would seem that the descent towards the glacier proper from the plateau is by a series of terraces. We lost sight of the land to-day, having left it all behind us, and now we have the waste of snow all around. Two more days and our maize will be finished. Then our hooshes will be more woefully thin than ever. This shortness of food is unpleasant, but if we allow ourselves what, under ordinary circumstances, would be a reasonable amount, we would have to abandon all idea of getting far south.

December 27 If a great snow plain, rising every seven miles in a steep ridge, can be called a plateau, then we are on it at last, with an altitude above the sea of 9820 ft. We started at 7 a.m. and marched till noon, encountering at 11 a.m. a steep snow ridge which pretty well cooked us, but we got the sledge up by noon and camped. We are pulling 150 lb. per man. In the afternoon we had good going till 5 p.m. and then another ridge as difficult as the previous one, so that our backs and legs were in a bad way when we reached the top at 6 p.m., having done 14 miles 930 yards for the day. Thank heaven it has been a fine day, with little wind. The temperature is minus 9 Fahr. This surface is most peculiar, showing layers of snow with little sastrugi all pointing south-south-east. Short food makes us think of plum puddings, and hard half-cooked maize gives us indigestion, but we are getting south. The latitude is 86 19 South to-night. Our thoughts are with the people at home a great deal.

Next page