A LSO BY F.A. W ORSLEY

Shackletons Boat Journey

Sir Ernest Shackleton

Endurance

A N E PIC OF P OLAR A DVENTURE

BY F. A. WORSLEY

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

to the memory of my friend

SIR ERNEST SHACKLETON

to his family, to our folk

and all our shipmates

Acknowledgment

I N thanking Lady Shackleton for her help and photographs I recall joyous days that I and others of Sir Ernest Shackletons men spent at Eastbourne, and his delight at being home again with his family and able to entertain his comrades.

I thank Messrs. Heinemann for their kind permission to use four pictures from Shackletons book South, and the Royal Geographical Society and the Discovery Committee for their courtesy in supplying me with prints of many of the photographs reproduced herein.

But particularly are my thanks due to the late Phyllis Lewis, to whose suggestion this book is due, for her valuable co-operation and aid in the arrangement and sequence of the book. She was the bravest soul I know.

F. A. W ORSLEY

London, March 1931

Contents

VIII. The Crossing of South

Georgia

Illustrations

Preface

BY P ATRICK OB RIAN

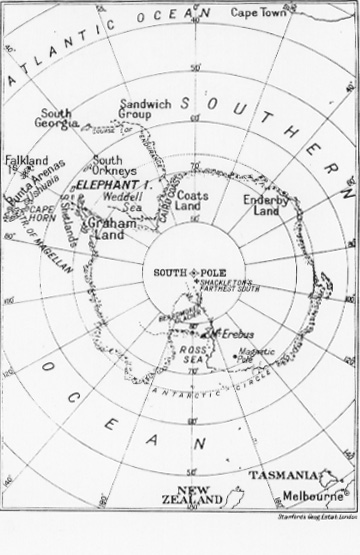

E RNEST S HACKLETON , an Irishman from Kilkee in the County Clare, was born in 1874 and educated at Dulwich, an English public school; he then joined the Merchant Navy, and as a lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve he sailed with Scott on his fatal expedition to the Antarctic. Yet before Scott began his unhappy inland march, Shackletons health broke down, probably from over-exertion, and he was obliged to be sent home. But in January 1908 he set out again for the South Pole in Nimrod, heading another expedition; and when he and some other members had climbed the enormous Beardmore glacier they came within 97 miles of the Pole, travelling up from the south, of course, from the comparatively sheltered Ross Sea: but at that point they had to turn back for want of food.

When he returned to England he was knighted and was made a Commander of the Victorian Order. But he could not rest easy until he was in those grim waters again and he set about organizing yet another attempt. He was busy in his Burlington Street office, collecting funds for the Imperial Antarctic expedition designed to cross the vast Antarctic continent from the north while another ship, the Aurora, should sail to the other side, to the Ross Sea, to take the members of the expedition off when they had completed their traverse. He was arranging countless details and recruiting officers and seamen who came up to his very high standards when Frank Arthur Worsley, the author of this book, came in, moved by a prophetic dream. Both men had served in the Merchant NavyWorsley had commanded several small vessels and he was now second officer in a ship bound for Canadaand they understood one another very well. It soon became apparent that Worsley longed to join the company, and presently Shackleton said Youre engaged. Join your ship until I wire for you.

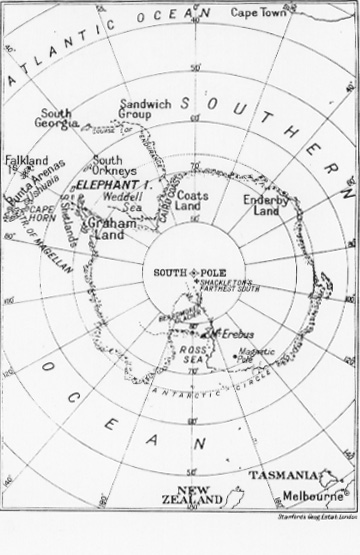

On 1 August 1914, when the coming of the war was by no means apparent to the world in general, Shackletons Endurance sailed for the northern shores of the Antarctic, and by 13 July 1915 she was in the middle of the Weddell Sea, 400 miles from the continent itself and a thousand from the whaling station in South Georgia. July was midwinter in those latitudes and the ship was entirely icebound: at this point neither seals nor penguins were any longer to be seen. Sea, ice and wind were extraordinarily wicked, and the creatures knew by instinct what was to come; and so, from experience of Polar seas, did Shackleton who soon told Worsley that the ship was doomed, very strongly built though she was, and with tapering sides to prevent the closing ice from crushing her. Immediately after this the first officer appeared. The play can begin, Sir, he said to Shackleton, whenever you are ready.

We shall all be in the Ritz (our name for the living quarters in the hold of the ship) in five minutes. You can go back and say so.

A preface is not a summary, God forbid, and this little piece is quoted solely to give Worsleys general tone: he draws Shackleton with the closest attentioneven devotionand here as in many other places he shows Shackleton as a seaman superior to those under his command, picked, experienced men though most of them were. But Worsley is largely indifferent to his other shipmates. There was an artist aboard, said to have come to paint the extraordinary Polar seascapes, and above all colours; but he is mentioned only once, when he finished off the caulking of a boat with his oil paints and a little seals blood. Much the same applies to the medical men and the naturalist, although they must have messed with him. Upon the whole, therefore, his fellow-men, apart from Shackleton and a few of the hands, did not interest him much. What he concentrated upon with the closest and most intelligent perception was the sea in all its countless forms, the snow, the ice, the currents and the truly appalling winds of those latitudes, far below the Roaring Forties of evil reputation. He is a sailor through and through, very highly skilled in his calling and often remarkably successful in describing various aspects of it: he possessed a highly developed aesthetic sense and he was deeply moved by the extraordinary beauty of Polar colour, its clarity, its prismatic brilliance in the more-than-frozen air, the unimaginable beauties of the ice, of tumbled, shattered pack-ice and of majestic bergs, large as half the county.

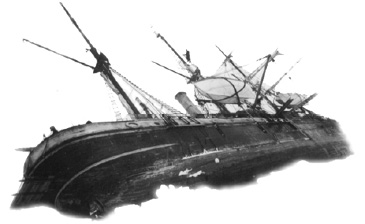

The Endurance s sides did indeed prevent the ice from crushing her by sideways pressure, as so many whalers have been crushed, and even men-of-war; but if a steel wedge is driven between two prodigious blocks of ice and the lateral pressure mounts to some millions of tons, the wedge is likely to be squeezed out: this is what happened to Endurance. She rose to the surface of the ice and stood there almost upon her keel, with a heavy list to port. Blizzards and very strong winds were an everyday occurrence and presently she fell right over with a perfectly enormous crash, terrifying the huskies, the powerful northern dogs that were to pull the sledges.

With infinite toil they righted her (there were only twenty-nine of them, including Shackleton) but she settled in the water and leaked so cruelly that they had to pump for seventy-two hours without a pause. And when they had her really dry, the winds and currents of the Weddell sea converged from three directions, driving the massive pack-ice upon her. Two great floes, one on each side, held her fast; a third struck her stern, tearing off her rudder and mortally wounding her keel. The ships timer-ends opened; water poured into her. They had time to unload some of the stores, the sledge-dogs and the boats on to the floe: then, when the pack-ice round her loosened, she went down.

It is not for an introducer to enumerate the almost incredible hardships they endured in those ice-coated boats over so immense an extent of ocean, nor to speak of the prodigious courage with which they bore them: but it may properly be said that after a great variety of disasters most of the people were landed on Elephant Island, as dismal a place as can well be imagined, while the stronger men took the remaining boat, the James Caird, to South Georgia, where they landed where they could and walked the rest of the way to the whaling station over country little more hospitable than the moon, except for the albatross chicks (fourteen pounds apiece) and a seven-foot sea-elephant. Yet throughout this boat-voyage, or rather these boat-voyages, Worsley was continually at Shackletons side, and he, in this long, very highly detailed book, is the man to write about him.

Next page