Copyright

Copyright Bob Chaulk, 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5.

Nimbus Publishing Limited

3660 Strawberry Hill Street, Halifax, NS, B3K 5A9

(902) 455-4286 nimbus.ca

Printed and bound in Canada

nb 1482

Editor: Angela Mombourquette

Design: Rudi Tusek

Cover design: Jenn Embree

Many photos from the authors collection are courtesy the estate of Greg Cochkanoff.

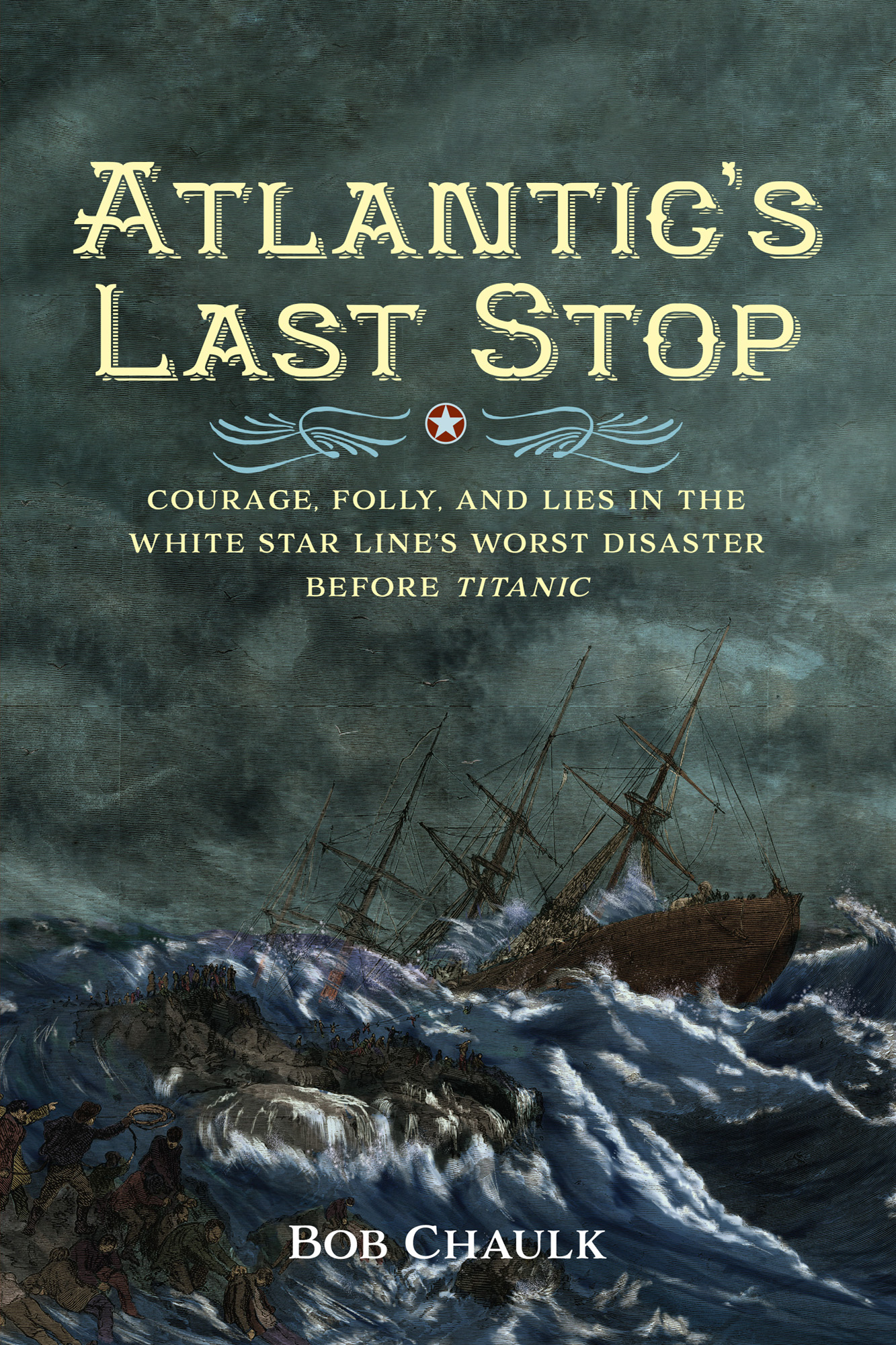

Cover image: From Harpers Weekly, April 19, 1873.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Atlantics last stop : courage, folly, and lies in the White Star Lines worst disaster before Titanic / Bob Chaulk.

Names: Chaulk, Bob, author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210215674 | Canadiana (ebook) 20210215704 | ISBN 9781774710104 (softcover) | ISBN 9781774710111 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Atlantic (Ship : 1870-1873) | LCSH: ShipwrecksNova ScotiaHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC G530.A84 C53 2021 | DDC 910.9163/44dc23

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia. We are pleased to work in partnership with the Province of Nova Scotia to develop and promote our creative industries for the benefit of all Nova Scotians.

Dedication

Dedicated to the memory of the men and women

of Meaghers Island, Ryans Island, and Lower Prospect,

whose lives were thrown into turmoil

by the arrival of some four hundred men who

had to be rescued from the sea, resuscitated,

warmed, accommodated, nursed, fed, and clothed.

Epigraph

Next morning when the sun arose, as the angry billows swelled, The people on the Prospect shore a fearful sight beheld. The rocks around were strewn with dead as each wave broke oer, Bearing its load to be laid with sorrow on the shore.

John Boutilier

The Atlantic Ballad (1885)

Chapter 1

The Ismays

The great credit of the unexampled success of the White Star Line is undoubtedly due to Mr. T. H. Ismay...who has so admirably overcome the difficulties which were presented to him in the enterprise of the White Star Line.

The Nautical Magazine for 1876

On April 21, 1863, Henry Ismay Metcalfe went to sea. It was an important and inevitable milestone in the life of a sixteen-year-old male from a seafaring family. Henrys vocation was to become a master mariner, like his father and brother. For the next four years he sailed the world aboard the 700-ton clipper Birkby, which had been built at Ritson and Sons shipyard in his hometown of Maryport, England.

Maryport was on the northern extremity of the Irish Sea and formed a triangle with two important cities. About 150 miles to the west in Northern Ireland was Belfast, poised to become one of the worlds great shipbuilding centres. The same distance to the south, at the mouth of the Mersey River, sat the historic seaport of Liverpool. Both these places would hold prominence in Henrys life. Connections were everything in those days. The expression Its not what you know but who you know, defined how things were done. Henrys father, George, a shipowner himself, was, no doubt, acquainted with the Birkbys owners, Hayton and Simpson, and would have arranged for his son to start his seafaring career on one of their ships.

Thomas Henry Ismay was another son of Maryport who would be important in Henrys life. He was Metcalfes first cousin, ten years his senior, and already a prominent name among Liverpool shipowners. Thomass father, Joseph Ismay, and Henrys mother, Ruth Ismay, were brother and sister. Thomas had also started his career at age sixteenas an apprentice with the Liverpool ship brokerage firm of Imrie, Tomlinson, and Company. When the apprenticeship ended, he too went to sea to gain first-hand experience of the ocean and the operation of ships. He had no intention of remaining a sailor. Upon his return to Liverpool, he went into business and in 1858, at the age of twenty-one, he became a partner with Philip Nelson, a friend of his father. The firm of shipowners and insurance brokers was called Nelson, Ismay, and Company. Nelson retired five years later, in 1863, and the new firm of T. H. Ismay and Company came into being.

By then, Thomas Ismay was owner or part owner of dozens of world-ranging ships, some of which flew the flag of a company called the White Star Line of Packets. Packet ships originated with the post office. They carried the mail, always travelling on an established route on a published schedulesomething that seems obvious today but was unusual in the mid-1800s. The line had been around since 1845, trading mostly with Australia. Like many shipping firms of the day, its owners were faced with two innovations that would forever change travel on the oceans: wooden ships were giving way to iron ships, and sails were giving way to steam engines, resulting in bigger and faster ships. Thomas Ismay would be an agent of those changes, which would precipitate an unprecedented magnitude of disasterdisaster that Thomas and his son Bruce would both experience.

The transition to iron and steam was expensive and difficult, and the White Star Lines owners chose a bad time to attempt the change. The Royal Bank of Liverpool failed in 1867, and Henry Wilson, the White Star Lines principal shareholder, was bankrupted. He was forced to divest himself of the money-losing firm. Never one to miss an opportunity, young Thomas Ismay purchased the name, flag, and goodwill of the defunct company at fire-sale prices, with the plan to eventually succeed where Wilson had failedby acquiring passenger steamships to operate on the crowded but lucrative North Atlantic. The market was dominated at that time by Cunard, a company started by the visionary Samuel Cunard of Halifax, Nova Scotia.

At that time, Thomas Ismays cousin, Henry Metcalfe, passed the requirements for the British Board of Trade certificate for second mate. On April 23, 1867, at the age of nineteen, Metcalfe became qualified to serve as an officer on an ocean-going ship registered anywhere in the British Empire.

A year later, on March 21, 1868, Thomas Ismay inaugurated his new business by dispatching to Melbourne the 750-ton iron sailing ship Explorer. By this time, the total sailing tonnage of his firm amounted to nearly 40,000 tonsbetween thirty and forty shipsengaged in trading with Australia, California, the west coast of South America, the River Plate in Argentina, India, the West Indies, and Mexico. On board as second mate of the Explorer was his cousin Henry Metcalfe. As Ismay had benefitted from family connections, he did his duty by seeing that his cousin did also. The voyage was auspicious for both of them.

Thomas Ismay was ambitious and shrewd. He wasnt satisfied to own shares of wooden sailing ships. While he was happy enough to carry goods to and from Australia as long as it was profitable, his real vision was for taking emigrants to America. There was a rising tide of migration to the New World and Ismay saw a lot of opportunity. Though he was reasonably wealthy by this time, building ships of the size and sophistication he wanted would take some major financing and dealmaking.

Next page