B OOKS BY F REDERICK B USCH

FICTION

Girls (1997)

The Children in the Woods (1994)

Long Way from Home (1993)

Closing Arguments (1991)

Harry and Catherine (1990)

War Babies (1989)

Absent Friends (1989)

Sometimes I Live in the Country (1986)

Too Late American Boyhood Blues (1984)

Invisible Mending (1984)

Take this Man (1981)

Rounds (1979)

Hardwater Country (1979)

The Mutual Friend (1978)

Domestic Particulars (1976)

Manual Labor (1974)

Breathing Trouble (1973)

I Wanted a Year Without Fall (1971)

NONFICTION

A Dangerous Profession (1998)

When People Publish (1986)

Hawkes (1973)

Copyright 1999 by Frederick Busch

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by Harmony Books, a division of Crown Publishers, Inc., 201 East 50th Street, New York, New York 10022. Member of the Crown Publishing Group.

Random House, Inc. New York, Toronto, London, Sydney, Auckland

www.randomhouse.com

Harmony Books is a registered trademark and Harmony Books colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Busch, Frederick, 1941

The night inspector / Frederick Busch.1st ed.

1. Melville, Herman, 18191891Fiction I. Title.

PS3552.U814N54 1999

813.54dc21 99-11890

eISBN: 978-0-609-60768-8

v3.1

Grateful acknowledgment is given to the Library of Congress to reprint the following maps: on , General Map of the City of New York, by Louis Aloys Risse, 1900.

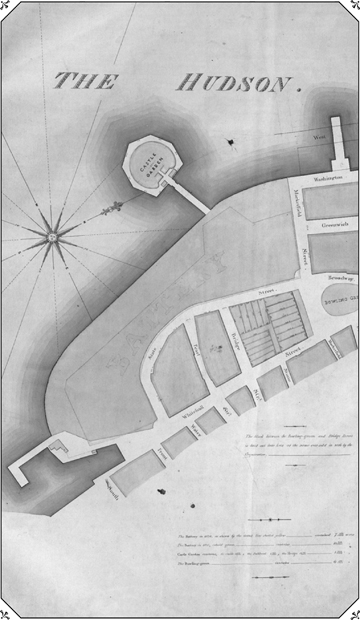

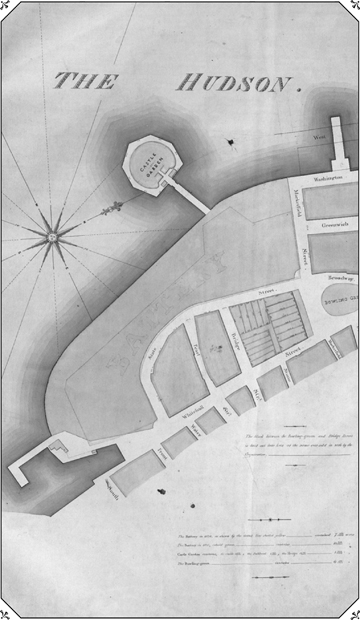

Grateful acknowledgment is given to the Manhattan Borough Presidents Office to reprint the following map: on , Untitled, by Daniel Ewen, 1827.

Grateful acknowledgment is given to the New-York Historical Society to reprint the following photographs: on , Broadway at Spring Street, c. 1868.

Dear Judy

I would, in sum, describe him as a man of size: Broad at the chest, long and thick of limb; and capable of flexuous motion, manifesting the dexterity and abandon, let us say, of the young New England brown bear in search of pike in icy rivers. He was known, once, to be fetching in his features: Saxon at the nose and jaw; clear of skin; evincing through all of his life, I am told, the trait I came to know so wellhis manner of peering about through half-closed eyes, as if he searched the distance, or as if, like the bear, he knew himself to be, whatever ground he trod, not far from peril.

He kept his silence, and he pondered Creation. He seemed not fearful of the Universe, but distrusting of its benevolence. He took care not to display his tenderness, most especially in regard to himself. He was, I lament to conclude, the most wounded of men, a tattered spirit in need of much repair.

S AMUEL M ORDECAI ,

Inspector of the Night

Contents

CHAPTER 1

N O MOUTH, I TOLD HIM .

If Im to craft a special order for you, he said.

What is that, a special order?

Why, this. He held up the sketch. I looked away from it. The mask, Mr. Bartholomew, he said. I make arms. I make legs. Ive never made a face, sir.

Through the smell of resin and shellac, through the balm of pine shavings, came the odor of his perspiration, and I thought of bivouac, and our stench on the wind. His thick, ragged, graying eyebrows were stippled with sawdust, as was his mustache. One of the knuckles of his broad hand was bloody, and the end of the other hands long finger had been cut away many years before and had raggedly healed.

Yes, I said. Special. I thought at first you meant order of being. Race. A species of man, perhaps. A special order of nature. I cannot abide such speculation. We have collectively demonstrated, and not that many months before, the folly of such thinking.

He smiled at the drawing, but not at me, and he shook his head. No, sir, he said. You are enough like the rest of my custom. Only your face is maimed, Mr. Bartholomew. You have your limbs, God forgive us.

I suggest that I am proof of His unreadiness to do so, I said.

We examined his sketch again, and he spoke to me of materials and money. It was to be of pasteboard, he decided, so that my head would not be weighed down. He would build many thin layers, each molded to the one beneath, and would protect them with paint, the better to keep away the deleterious effects of rain and snow. Withal, my head would not be burdened, on account of the lightness of construction. Like a little craft on the sea, he suggested. I had to smile. He had, it was clear, to look away.

And in the end, he prevailed, and he shaped me a mouth.

I did hear of several who used a buffalo gun, and at first I thought it a lie. How could you haul such a heavy piece of metal and wood up a tree? Not to mention aim with accuracy, or reload with speed? From a hilltop redoubt: yes. With a tripod under the front of that immense, octagonal barrel. But never in a tree, I thought, and of course I was wrong. It was one of my lessons in this long education I received about and from my native country. Never consider a feat undone if the reward is of a size. We move what we must, whether barrels of meat or kegs of dead flesh, when at the farther end of the transaction there lies a crate of dollars. That is how we fare westward, in spite of reversals, anguish, and death.

That is why some very few of us served with the volunteers of New York as what we called marksmen. Snipers, the men of infantry or horse called us, and, behind our backs, assassins. An Englishman I met said thugs. In the woods around Paynes Corners, where I was born, the hamlet lying two hundred miles and more from Manhattan, a small crossroads and then a church and a fur-trading shop for victuals, I learned my forest craftiness. I could hide, and I could seek. I was a solitary child, and powerful of limb. And I was reckless, and born with great vision, though not, alas, of the interior, spiritual sort. But I saw in the dark if there was a hint of a sliver of moon in the sky. How natural, then, with my youth and young manhood passed in patrolling a trapline and hunting for my meals, that I would make a marksman when called to the War.

It was a Sharps that I carried into the trees. I wore a pannier of sixty rounds, and always a pistol in a holster at my back. The knife I wore at my left side, and I drew with my right. It was good for game, and bad for men, I once told the sergeant who saw me out and up and hunting Rebels.