Copyright 2001 by Russell Drumm

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 0-395-98367-3

The line drawings are by Jeff Fisher.

The sail-setting illustration on is by Jason Biondo.

eISBN 978-0-547-79981-0

v2.0518

For Russell Malcolm Drumm

and Reta Hitchings Drumm,

who taught me to love life

He rises by lifting others.

Robert Green Ingersoll

Acknowledgments

I WOULD first like to express my gratitude to the greater Coast Guard family for giving me the opportunity to experience the esprit that allows a perennially underfunded and often underappreciated organization to perform its many duties so well.

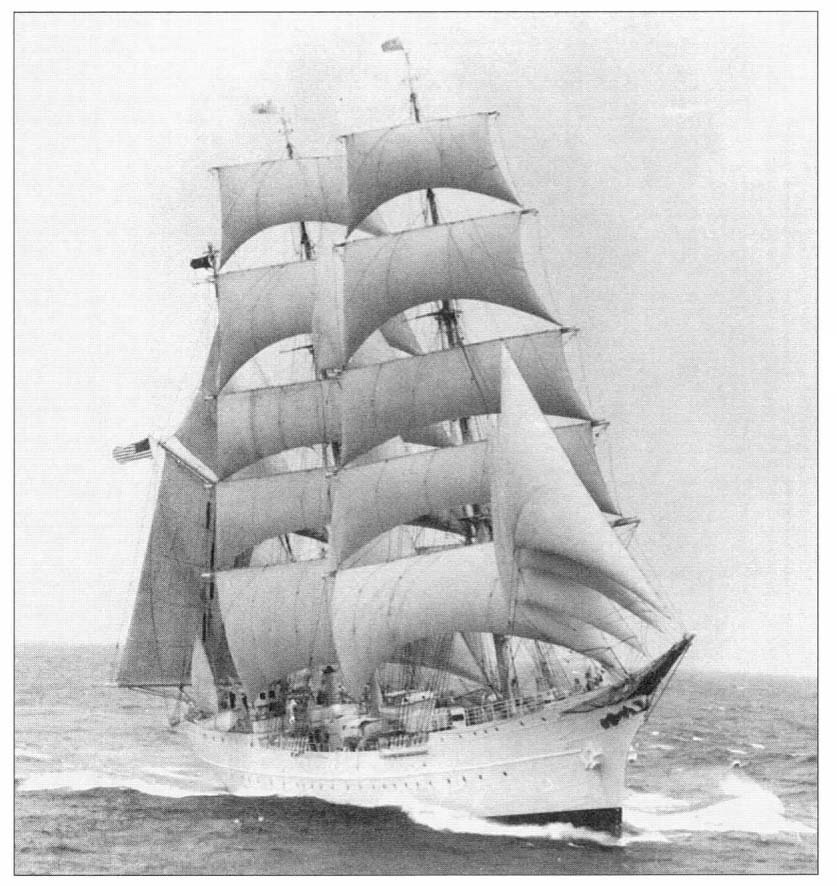

My thanks to Coast Guard historians Dr. Robert Browning and Scott Price. As for Eagle herself, lets have three cheers for the cadets, enlisted complement, and officers of the barque. There is much that she taught me. I offer my heartfelt thanks to former Eagle captains Paul Welling, David V. V. Wood, Patrick Stillman, Don Grosse, and Robert Papp and to current captain Ivan Luke; to lieutenant commanders Keith Curran and Cathy Tobias; to bosuns Keith Raisch, Doug Cooper, Rick Ramos, and Rick Birch; to petty officers Tracy Allen, Kelly Nixon, and Matt Welch; and to BM3 Greg Giggi. Thank you, Robert LaFond; I know our discussions were not easy.

There are two individuals without whom I could not have written this book. Karl Dillmann, Eagles square-rigger sailor, raconteur, and teacher extraordinaire, showed me a thousand reasons that this story should be told. The nation owes a great debt to Petty Officer Dillmann for helping to shape a few thousand Coast Guard officers over the past decade. And I extend my heartfelt thanks to Tido Holtkamp, a proud American who served on the barque as a German naval cadet in 1944 under the flag of the Third Reich. Mr. Holtkamps honest recollections of Germanys darkest hours and his invaluable translation skills have thrown light into long-forgotten corners of Eagles history.

Detlev Zimmerman, who now serves with the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, was a cadet on Horst Wessel in 1943 before joining Germanys U-boat fleet. Mr. Zimmermans translations and vivid recollections of World War II were extremely helpful to me. Thanks to my neighbor, Lynette Widder, a German scholar, who helped translate.

I have tried not to overstate Eagles German past, but it would have been wrong to ignore it. She is the product of a great German shipbuilding tradition, though she sailed under the German flag for just ten of her sixty-five years. Of course the decade from 1936 to 1946 was a hellish time, and the barque was lucky to survive it. I must thank the people of Blohm & Voss, the shipyard that built her, for their help.

And for their enlightening correspondence from across the Atlantic, I am sincerely grateful to Peter Jepsen, Otto Schlenzka, Ludwig Brenner, Gunther Tiegs, Otto Piepenhagen, Herman Adamowicz, Brigitte Jacobs, Siegfried Stiller, Karl Tadey, Hans-Joachim Meinke, Fritz Hugo, Karl Lederer, Marion Niemann, Willie Starck, Werner Fistler, Ludwig Brenner, Jrgen Gumprich, Karl Bethke, Heinrich Gutbier, Herbert Jander, and Paul Zock. Herbert Bhm, a fine journalist from Hamburg, deserves my special thanks for the research he so generously shared.

The only thing a writer with an idea really needs is a believer other than himself. I have been blessed with three. My very able agent, Emma Sweeney of Harold Ober Associates, recognized where I was going and deftiy parted the seas. Elaine Pfefferblit, Houghton Mifflins editor extraordinaire, led the way with a firm, guiding hand. Peg Anderson, manuscript editor, fine-tuned the prose and saw the manuscript through production. And thank you, Bill Henderson of Pushcart Press, for encouraging me to write books way back when.

Prologue

IT WAS on the deck of Coast Guard Patrol Boat 41934 on the night of July 17, 1996, that I realized the necessity of writing this book. Three of the boats crew members were struggling to lift aboard the body of a young woman, one of the 230 victims of TWA Flight 800. Much more lifting would be required before the sun rose again off Moriches, Long Island.

As a reporter for a local newspaper, I watched my job shrink to insignificance as our boat and others like it moved through the wreckage. I did not have to be there, but the young Coast Guard men and women retrieving bodies and hoping against all reason for survivors did. The manner in which they went about their work was a story that needed telling.

I was no stranger to the Coast Guard, having had a working relationship with my hometown station and having written a number of stories over the years about scary Coast Guard rescues of yachtsmen and fishermen in the northwest Atlantic. They were stories of heroism plain and simple, but they seemed to blurt from the page, incongruous among the routine drug arrests, meeting announcements, and posturing letters to the editor. Except within the shrinking fishing community, drowning in giant seas appears to have gone out of fashion, to be a primal throwback, something like being eaten alive. The flares in the night sky, the ropes and floats of rescue, seem primitive, like leeches applied to the sick. The general public translates such stories into fiction, our repository for acts too selfless to fathom. The professionalism I was witnessing on the Montauk stations 41-footer, though familiar to me, was of another ageit had roots. That quality is old but strong, spawned long ago on vulnerable, wind-driven ships, but it continues to breathe today.

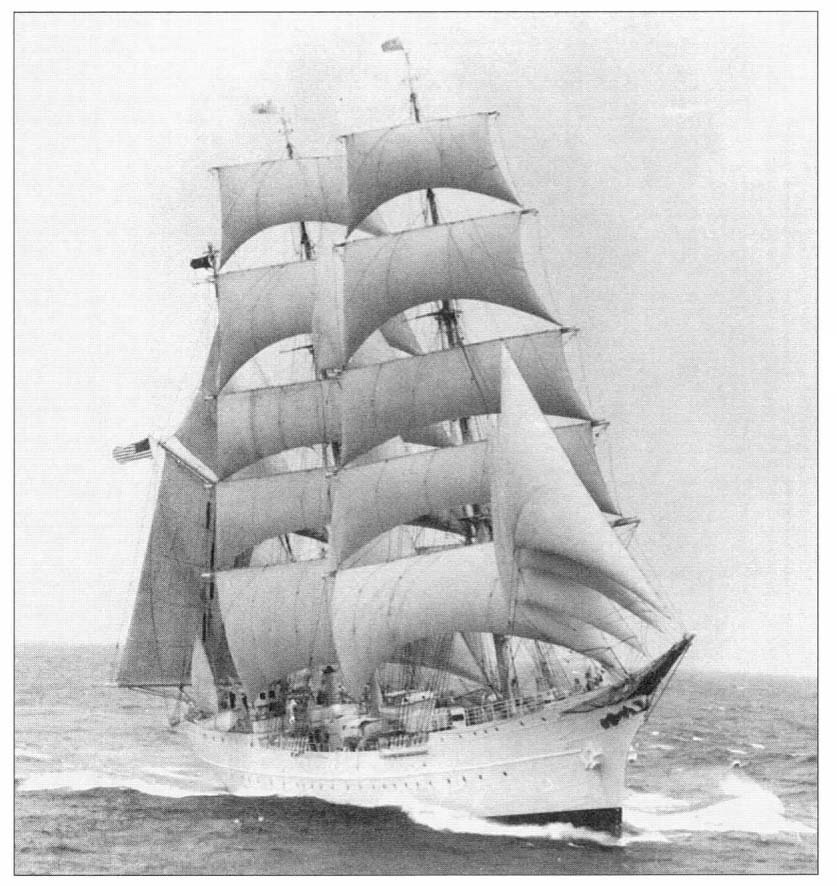

Two weeks earlier I had been aboard the barque Eagle, the Coast Guard Academys training ship, as she moved down the Elbe River from the city of Hamburg. The cadet training cruise that summer had included a visit to the old Hanseatic port on the occasion of the barques sixtieth birthday. In June of 1936 she had been christened Horst Wessel in honor of a Nazi martyr and put into service as a training ship for naval officers of the Third Reich. Adolf Hitler had attended the christening. Now, having been claimed and renamed by the Coast Guard after the war, Eagle trains rescuers.

There is good in the world and evil, heroes and villains, and a whole lot in between. There are ways to fall and ways to rise, to sink and to remain afloat. The Barque of Saviors is about falling and rising and staying afloat.

A few apologies. First, to those who are expecting a chanty-filled, blow-ye-winds-hi-ho profile of a sailing ship: Eagle is, indeed, a noble square-rigger, heir to one of the great shipbuilding traditions, but this book is more about her people and their worldsGermans during one of the darkest periods in history and Americans ever sinceand about the world of one man in particular. I apologize to the thousands of Coast Guard folks, active, retired, and passed over the bar, whose stories I was unable to tell. Finally, to readers who will confront nautical jargon for the first time: although Im proud to have been called shipmate, I cannot claim to be part of the Coast Guards extended family. I have, however, made an attempt to record its ancient language, and I include a glossary of nautical terms in the books after section.