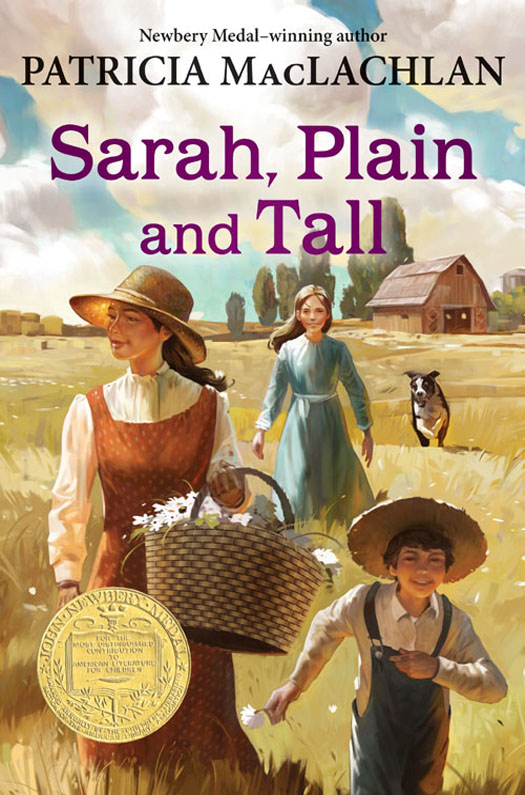

For old friends, dear friends DICK AND WENDY PUFF,

ALLISON AND DEREK Contents D id Mama sing every day? asked Caleb. Every-single-day? He sat close to the fire, his chin in his hand. It was dusk, and the dogs lay beside him on the warm hearthstones. Every-single-day, I told him for the second time this week. For the twentieth time this month. The hundredth time this year? And the past few years? And did Papa sing, too? Yes.

Papa sang, too. Dont get so close, Caleb. Youll heat up. He pushed his chair back. It made a hollow scraping sound on the hearthstones, and the dogs stirred. Lottie, small and black, wagged her tail and lifted her head.

Nick slept on. I turned the bread dough over and over on the marble slab on the kitchen table. Well, Papa doesnt sing anymore, said Caleb very softly. A log broke apart and crackled in the fireplace. He looked up at me. What did I look like when I was born? You didnt have any clothes on, I told him.

I know that, he said. You looked like this. I held the bread dough up in a round pale ball. I had hair, said Caleb seriously. Not enough to talk about, I said. I would have named you Troublesome, I said, making Caleb smile. I would have named you Troublesome, I said, making Caleb smile.

And Mama handed me to you in the yellow blanket and said... He waited for me to finish the story. And said... ? I sighed. And Mama said, Isnt he beautiful, Anna? And I was, Caleb finished. Caleb thought the story was over, and I didnt tell him what I had really thought.

He was homely and plain, and he had a terrible holler and a horrid smell. But these were not the worst of him. Mama died the next morning. That was the worst thing about Caleb. Isnt he beautiful, Anna? Her last words to me. I had gone to bed thinking how wretched he looked.

And I forgot to say good night. I wiped my hands on my apron and went to the window. Outside, the prairie reached out and touched the places where the sky came down. Though winter was nearly over, there were patches of snow and ice everywhere. I looked at the long dirt road that crawled across the plains, remembering the morning that Mama had died, cruel and sunny. They had come for her in a wagon and taken her away to be buried.

And then the cousins and aunts and uncles had come and tried to fill up the house. But they couldnt. Slowly, one by one, they left. And then the days seemed long and dark like winter days, even though it wasnt winter. And Papa didnt sing. Isnt he beautiful, Anna?No, Mama. It was hard to think of Caleb as beautiful.

It took three whole days for me to love him, sitting in the chair by the fire, Papa washing up the supper dishes, Calebs tiny hand brushing my cheek. And a smile. It was the smile, I know. Can you remember her songs? asked Caleb. Mamas songs? I turned from the window. No.

Only that she sang about flowers and birds. Sometimes about the moon at nighttime. Caleb reached down and touched Lotties head. Maybe, he said, his voice low, if you remember the songs, then I might remember her, too. My eyes widened and tears came. Then the door opened and wind blew in with Papa, and I went to stir the stew.

Papa put his arms around me and put his nose in my hair. Nice soapy smell, that stew, he said. I laughed. Thats my hair. Caleb came over and threw his arms around Papas neck and hung down as Papa swung him back and forth, and the dogs sat up. Cold in town, said Papa.

And Jack was feisty. Jack was Papas horse that hed raised from a colt. Rascal, murmured Papa, smiling, because no matter what Jack did Papa loved him. I spooned up the stew and lighted the oil lamp and we ate with the dogs crowding under the table, hoping for spills or handouts. Papa might not have told us about Sarah that night if Caleb hadnt asked him the question. After the dishes were cleared and washed and Papa was filling the tin pail with ashes, Caleb spoke up.

It wasnt a question, really. You dont sing anymore, he said. He said it harshly. Not because he meant to, but because he had been thinking of it for so long. Why? he asked more gently. Slowly Papa straightened up.

There was a long silence, and the dogs looked up, wondering at it. Ive forgotten the old songs, said Papa quietly. He sat down. But maybe theres a way to remember them. He looked up at us. How? asked Caleb eagerly.

Papa leaned back in the chair. Ive placed an advertisement in the newspapers. For help. You mean a housekeeper? I asked, surprised. Caleb and I looked at each other and burst out laughing, remembering Hilly, our old housekeeper. She was round and slow and shuffling.

She snored in a high whistle at night, like a teakettle, and let the fire go out. No, said Papa slowly. Not a housekeeper. He paused. A wife. Caleb stared at Papa.

A wife? You mean a mother? Nick slid his face onto Papas lap and Papa stroked his ears. That, too, said Papa. Like Maggie. Matthew, our neighbor to the south, had written to ask for a wife and mother for his children. And Maggie had come from Ten-nessee. Her hair was the color of turnips and she laughed.

Papa reached into his pocket and unfolded a letter written on white paper. And I have received an answer. Papa read to us: Dear Mr. Jacob Witting, I am Sarah Wheaton from Maine as you will see from my letter. I am answering your advertisement. I have never been married, though I have been asked.

I have lived with an older brother, William, who is about to be married. His wife-to-be is young and energetic. I have always loved to live by the sea, but at this time I feel a move is necessary. And the truth is, the sea is as far east as I can go. My choice, as you can see, is limited. This should not be taken as an insult.

I am strong and I work hard and I am willing to travel. But I am not mild mannered. If you should still care to write, I would be interested in your children and about where you live. And you. Very truly yours, Sarah Elisabeth Wheaton P.S. Do you have opinions on cats? I have one.

No one spoke when Papa finished the letter. He kept looking at it in his hands, reading it over to himself. Finally I turned my head a bit to sneak a look at Caleb. He was smiling. I smiled too. One thing, I said in the quiet of the room.

Whats that? asked Papa, looking up. I put my arm around Caleb. Ask her if she sings, I said. C aleb and Papa and I wrote letters to Sarah, and before the ice and snow had melted from the fields, we all received answers. Mine came first. Dear Anna, Yes, I can braid hair and I can make stew and bake bread, though I prefer to build bookshelves and paint.

My favorite colors are the colors of the sea, blue and gray and green, depending on the weather. My brother William is a fisherman, and he tells me that when he is in the middle of a fog-bound sea the water is a color for which there is no name. He catches flounder and sea bass and bluefish. Sometimes he sees whales. And birds, too, of course. I am enclosing a book of sea birds so you will see what William and I see every day.

Very truly yours, Sarah Elisabeth Wheaton Caleb read and read the letter so many times that the ink began to run and the folds tore. He read the book about sea birds over and over. Do you think shell come? asked Caleb. And will she stay? What if she thinks we are loud and pesky? You are loud and pesky, I told him. But I was worried, too. Sarah loved the sea, I could tell.

Maybe she wouldnt leave there after all to come where there were fields and grass and sky and not much else. What if she comes and doesnt like our house? Caleb asked. I told her it was small. Maybe I shouldnt have told her it was small. Hush, Caleb. Hush.

Calebs letter came soon after, with a picture of a cat drawn on the envelope. Dear Caleb, My cats name is Seal because she is gray like the seals that swim offshore in Maine. She is glad that Lottie and Nick send their greetings. She likes dogs most of the time. She says their footprints are much larger than hers (which she is enclosing in return). Your house sounds lovely, even though it is far out in the country with no close neighbors.