North has meticulously researched the myriad details that render this story so true to life and cast a new light on our origins.

Irina Dunn, former director of the New South Wales Writers Centre

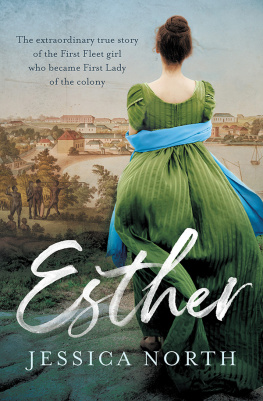

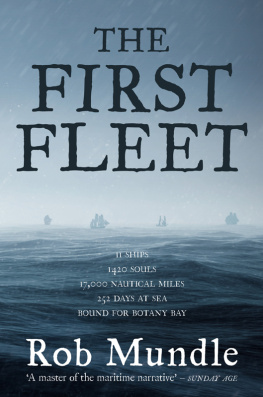

Jessica North has really brought to life the story of Esther, the young First Fleet convict who, for a brief period in 1808, became the First Lady of the British colony in Sydney Cove.

Helen Bersten OAM, former Honorary Archivist, Australian Jewish Historical Society

Jessica North has been researching Esthers story for over a decade, discovering intriguing new details along the way. She is a program director at the Australian Research Institute for Environment and Sustainability at Macquarie University, and author of several guides.

First published in 2019

Copyright Jessica North 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76052 737 2

eBook ISBN 978 1 76087 097 3

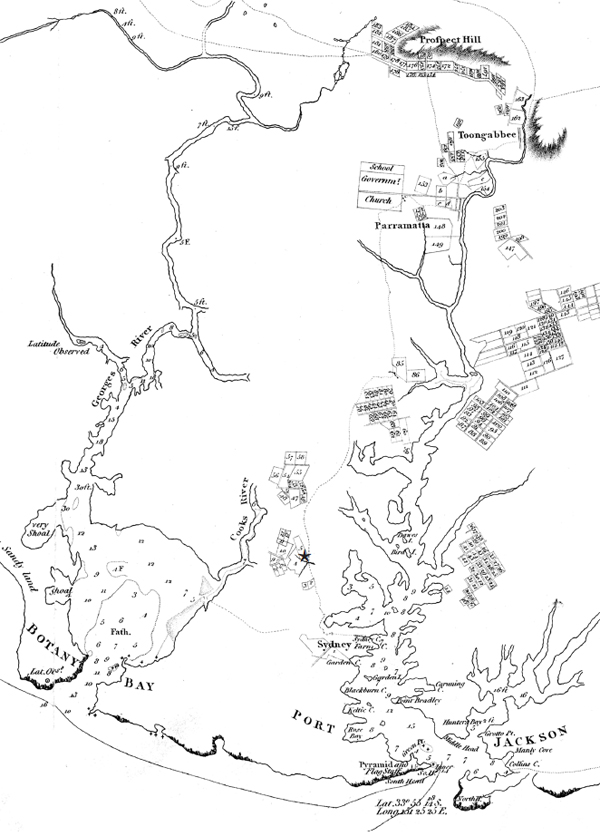

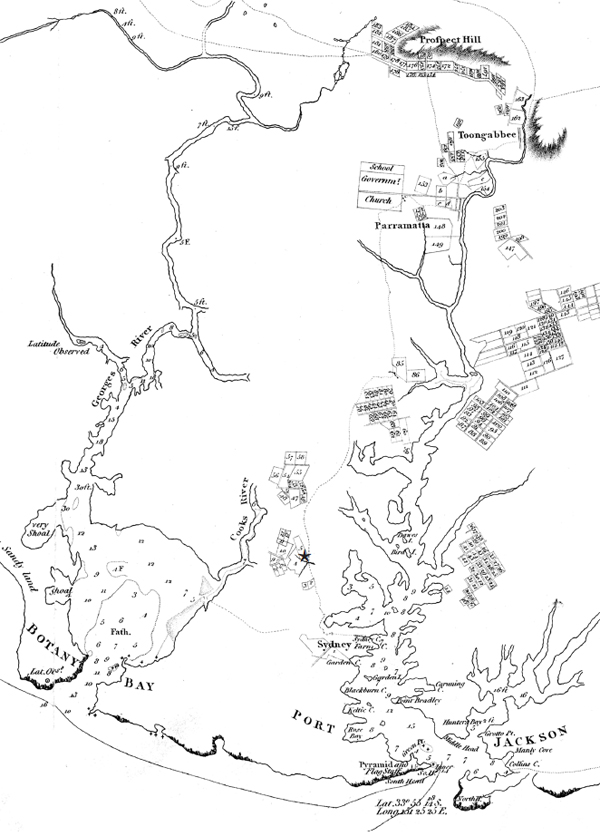

Map on p. vi is from the Dixson Map Collection, State Library of New South Wales

Cover design: Lisa White

Cover photographs: Ilina Simeonova, Trevillion Images;

View of Sydney, from the East Side of the Cove, No. 1,

by John Eyre, c. 1808, State Library of New South Wales (background)

For Stephen

Map of Sydney Cove from 1799. George Johnstons initial land grant at Annandale (no. 5) is marked with a star. The Parramatta road ran past the property.

This is the story of a remarkable woman. Arriving in New South Wales as a convict on the First Fleet, Esther Abrahams roselike Cinderella herselffrom the very bottom of society to its top. She had none of the advantages of education and social standing enjoyed by her contemporary Elizabeth Macarthur, and yet she achieved similar success in the management of a large agricultural estate.

Once I had discovered Esther, I was keen to find out more. I read hundreds of books and articles, some of which provided only small threads of detail that, when woven together, created the colourful tapestry of Esthers life. In the process, I came across several previously unknown documents.

People make history. And it is not until we get to know the people behind historic events that we really understand what they were all about. Esthers life was intertwined with all the major events of the early colony and so, through her, we meet the principal figures of the timeboth British and Indigenousand see how their interrelationships influenced the historical outcomes.

I relied heavily on personal journals and letters, family and historical records, transcribed conversations, and of course the published work of many wonderful historians. Even the initially daunting volumes of the Historical Records of New South Wales became welcome friends, once I was familiar with the people who wrote the letters and reports they contain.

The office in Britain that was responsible for the colonies was initially the Home Office but was later called the Colonial Office, the War Office, and finally the War and Colonial Office. To avoid confusion, I have continued to refer to it as the Colonial Office. I have also called the medical men of the time doctors (rather than surgeons), and have used surnames for men and first names for women.

I have incorporated an accurate timeline throughout the book and have not changed any known facts. Where gaps exist in the records, I have described a possible set of events.

All the people in this story are real. Their names are sprinkled through Sydneys places, and echoes of their characters remain in Australias egalitarian society. One of the most intriguing of them is Esther. I hope you enjoy meeting her as much as I did.

30 August 1786

30 August 1786

Sixteen years old. Frightened. And feeling sick. Esther was standing in the dock at the Old Bailey in London. She was on trial for stealing twenty-four yards of black silk lace, worth fifty shillings. And shoplifting carried a death sentence.

Esther did not look like the women who usually stood in that place. For a start, she was better dressed. Her elegant gown of Indian chintz befitted an officers daughter, and her dark, wavy hair was gathered fashionably behind her head with wispy curls nestling either side of her face.

Though she felt shaky, she was doing her best to hold her head up and appear composed. She kept her large hazel eyes focused on the wall behind the judge to avoid catching the eye of her father, who sat in the public area to her right.

Major Julian had taken the unusual step of engaging a barrister to defend his daughters case, and that barrister was pacing to and fro as he teased conflicting details from the second of two witnesses. William Garrow would later become famous for introducing the concept of presumed innocent until proven guilty, but in 1786 he had been at the bar for only two years. He called three more people to appear before the court, who all declared Esther to be of very good character, and then the short trial was over.

While the twelve men of the jury huddled in the back corner of the courtroom to decide their verdict, Esther wiped her sweating palms down the side of her skirt. She stole a glance at her father. His head was thrown back, his eyes were closed and his hands were pressed together, with the tips of his fingers resting against his chin.

The jury foreman turned back towards the judge. Esthers heart pounded.

Guilty of stealing! the foreman announced.

Esther gasped.

but not privately.

That lesser offence, which meant that the shop assistant had been aware of the theft, allowed the judge to at least waive the mandatory death penalty in favour of a lesser one. He sentenced Esther to be transported to parts beyond the seas for seven years. Her father let out a groan.

As a gaoler marched her into the adjacent Newgate Prison and along its dark granite corridors, Esthers mind was numb. The man, who smelt of gin, shoved her into a large cell crammed with more than a hundred other women, and he slammed the door shut behind her.

30 August 1786

30 August 1786