Published in the United States of America in 2009 by

CASEMATE

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

and in the United Kingdom by

CASEMATE

17 Cheap Street, Newbury, Berkshire, RG14 5DD

2009 by Niklas Zetterling, Michael Tamelander and Norstedts Frlagsgrupp AB

Translation 2009 Niklas Zetterling

Photos John Asmussen, www.bismarck-class.dk

ISBN 978-1-935149-18-7

eISBN 978-1-61200-0497

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress and from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact

United States of America

Casemate Publishers

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail casemate@casematepublishing.com

Website www.casematepublishing.com

United Kingdom

Casemate-UK

Telephone (01635) 231091, Fax (01635) 41619

E-mail casemate-uk@casematepublishing.co.uk

Website www.casematepublishing.co.uk

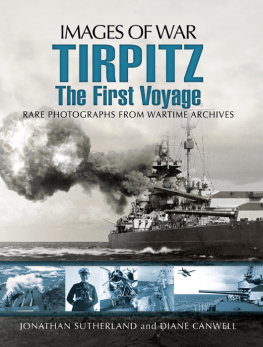

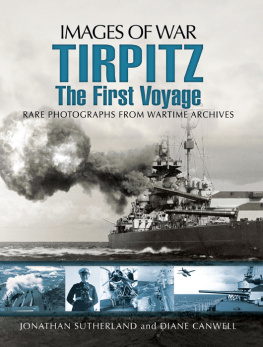

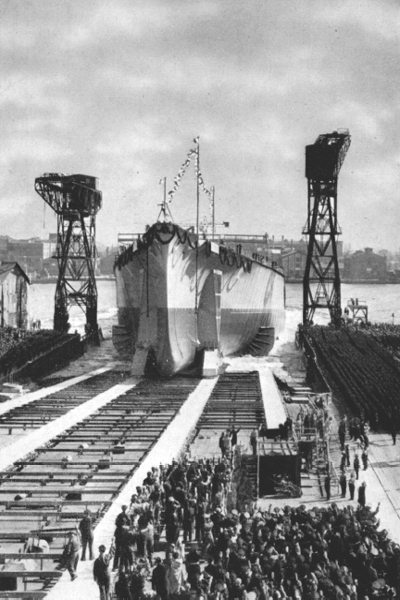

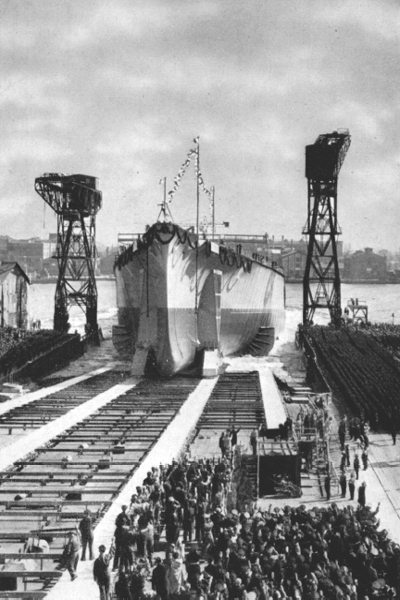

The launch of the Tirpitz on April 1, 1939.

Preface

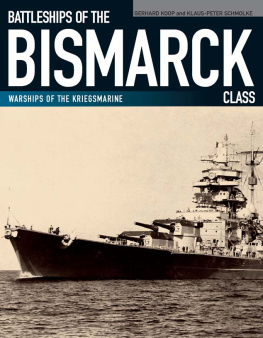

When working on our previous book about the battleship Bismarck , whose career turned out to be as brief as it was dramatic, it was impossible not to make comparisons with the fate of her sister ship, the Tirpitz . The lattercommissioned after the destruction of the Bismarck and despite being Germanys largest warshipremained stationary and unharmed for most of her service. As the fates of the two ships differed considerably, the way we approached the story of the Tirpitz also differs significantly from the way we approached Bismarck . The latter was the focal point of a highly dramatic week in May 1941. Of course, there was the bigger picture in which she temporarily played a part, but the narrative was built around the battleship herself, the fate of the crew manning different battle stations, and also around the commanders who made decisions that would have important implications for maritime strategy in the later parts of the Second World War.

In a sense, the Tirpitz was a focal point too, but rather as a piece in a broader game played by actors located very far from the battleship herself. The drama of the Tirpitz did not to the same extent take place on the bridge or at the battle stations of the ship. Instead, several dramatic episodes unfolded around her, as she was continuously regarded as a major threat by the Allies. Most of these episodes took place in one of the most inhospitable parts of the earththe Arctic Sea. During the summer months, this region could offer spectators a scenery as tranquil as it was dazzling. The winters, though, could be very severe. Despite the harsh climate, many merchant ships were sent to Murmansk and Archangelsk, bringing vital armaments and other important cargo from the Western Allies to the Soviet Union. The Tirpitz constantly threatened these convoys, and innumerable attempts were therefore made to destroy her. The German battleship, however, long defied these efforts.

There are many very good sources if one wants to study the history of the Tirpitz . Most of her war diary still remains, as do many relevant documents from the Luftwaffe and various German naval staffs. Also, a large part of her crew and many additional eyewitnesses survived the war. With so many sources available, priorities have to be made in order to produce a readable account. We have chosen not to describe the Tirpitz from a technical point of view, since we have already discussed her almost identical sister ship in our previous work. Instead we have focused upon the war in the Arctic, the convoys and the Allied efforts to destroy the battleship. No warship presents an isolated history. Not until the full picture is clear, can the importance of the Tirpitz be judged. With this book we hope to assist the reader in attaining a better understanding of the war in the Arctic, as well as the Tirpitzs role in it. This was our main objective.

Prologue

Despite his warm clothes, Lieutenant Commander Sommer suffered from the bitter cold. It penetrated his boots and proceeded up his legs until his entire body felt frozen. Already as a young cadet, he had learned how to relax to ignore the cold, but this technique seemed to be ineffective as he stood on the pier and gazed upon the huge battleship lying at anchor in the roadstead.

At this time of the year the days were very short, with late mornings and the dusk coming early. Presently, the sun had risen above the white mountains. It made the trees cast shadows and created a yellowish glow on the battleship. The asymmetric camouflage, which was intended to break up the contours of the ship, had been painted over. Instead, the hull and parts of the superstructure had been dyed dark grey, while higher parts had been given a lighter grey surface, to blend with the snow-clad mountains slopes surrounding the battleships mooring place. Despite the distance, Sommer could also discern the many buoys on the water above the torpedo nets.

With a length of 251 meters, the Tirpitz like her almost identical sister ship Bismarck , which had been sunk on the Atlantic in May 1941was an impressive spectacle, even though the majestic mountains surrounding Troms diminished her appearance by comparison. Since she had been accepted by the German Navy on 25 February 1941, the British had feared her, but she had seldom been allowed an opportunity to fire with her eight 38cm guns upon an enemy. Rather, she had long been a hunted prey, subjected to innumerable British attacks. Except for an air attack in April 1944, her complement of more than 2,000 had always escaped virtually unharmed.

The latest air attacks however had damaged the battleship significantly. In fact, she could no longer be regarded as fit for action. She had been lying in Kaafjord and been given superficial repairs, but the damage to her bow did not allow speed much in excess of ten knots. In such circumstances, it was utterly unthinkable to challenge the Allied command of the seas. She was still a weapon, though, and had thus been sent to her mooring near Kvalya, to assume the role of a floating battery. To the crew of what was deemed to be one of the worlds most powerful battleships, it was an ignominious task, but it was no fault of theirs.

As the battleship was no longer expected to sail on the open seas, some 600 of the crew, mainly from the machinery, had been transferred to land duties and were commanded by Sommer. They were to establish anti-aircraft cover, operate fog projectors, and ensure that the ship was protected by nets to ward off torpedoes and submarines. Still, some 1,700 men remained on boardgun crews, electricians, sailors, and officersto perform duties whose significance had paled. When Germany still had some sort of chance to win the war, which had begun in Poland in 1939, the struggle in the Arctic Ocean had been part of the conflict, in which the Tirpitz significantly influenced the decisions taken on both the German and the Allied sides. Now she had been reduced to a static role in a remote area of little significance. Soviet forces were already on the German eastern borders, as were Allied troops in the west. There was nothing the crew could do about it, stuck as they were in the crippled battleship far up in the north. Sommer shivered. In the battleship it was at least warmer. He really yearned for the warmth on board.