EUMENES Publishing 2019, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

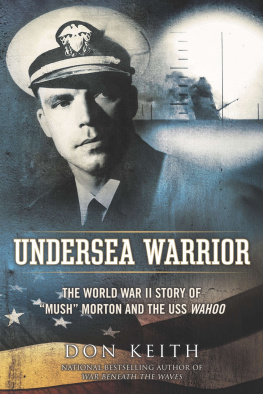

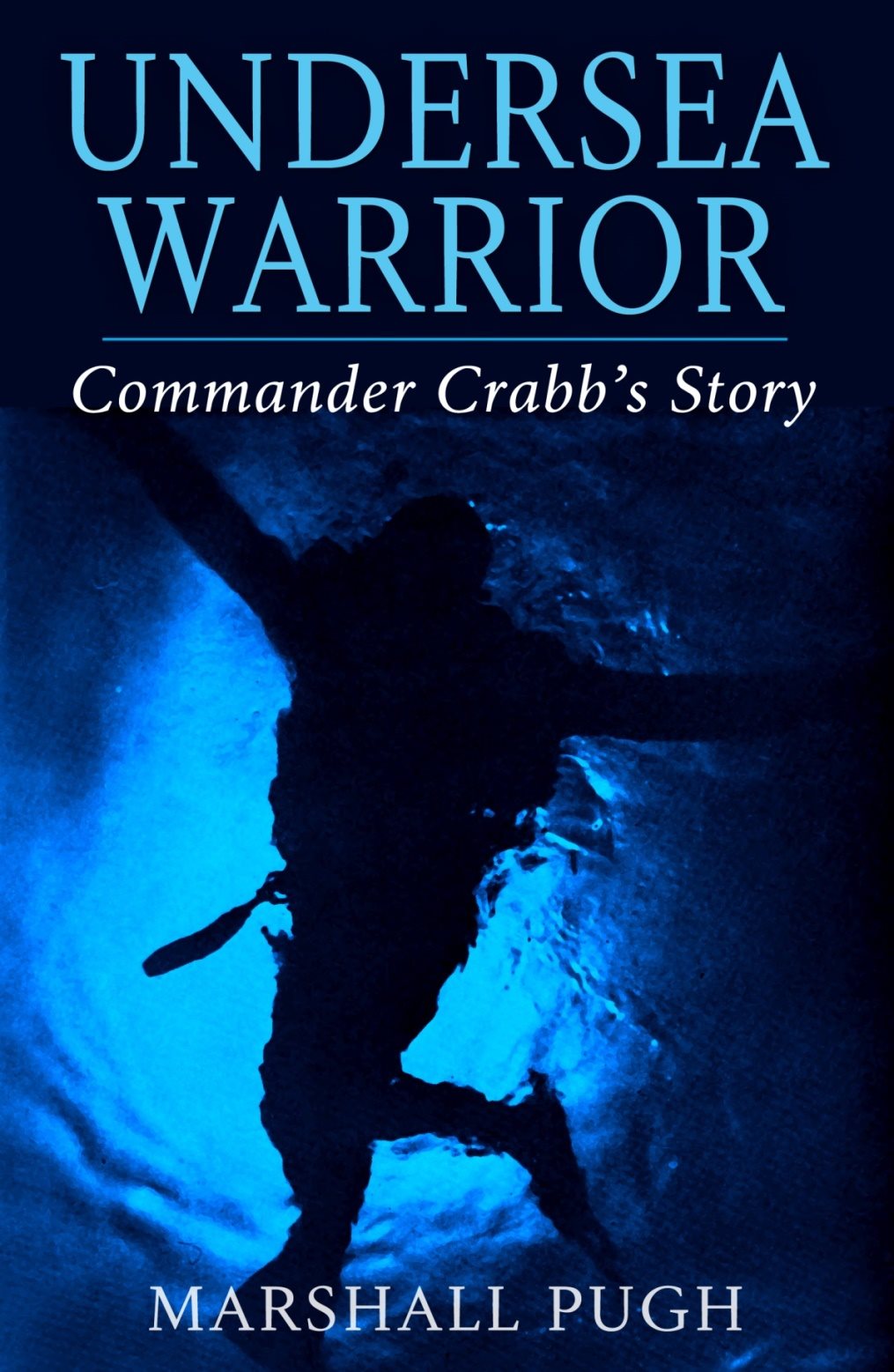

UNDERSEA WARRIOR

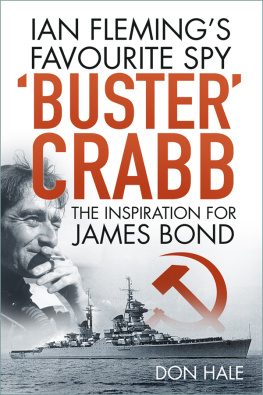

Commander Crabbs Story

By

MARSHALL PUGH

Undersea Warrior was originally published in 1956 as Frogman by Charles Scribners Sons, New York.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

FOREWORD

When Commander Crabb left the Navy in the spring of 1955, we began to work together on an account of his career. It was a slow job, for whenever I pressed him for information which would show him in a brave or generous light, he would break off, abruptly remember that he had another appointment or suggest that we should take my daughter for a walk. Crabb liked to talk about his comrades and about the Italian frogmen who were technically his enemies and who later became his friends. He was never wholly convinced that there was much need to talk about himself.

Fortunately, there were many others who appreciated the work which Crabb had done, and I should like to thank them, particularly Lieutenant Joseph Howard, R.N.V.R., M.B.E., who first suggested that the book should be written; Chief Petty Officer Ralph Thorpe, Petty Officer David Bell, G.M., and Leading Stoker Sydney Knowles, B.E.M., of the Underwater Working Party; and Prince Junio Valerio Borghese for his personal help and permission to draw from his book The Sea Devils .

Commander Crabb disappeared in Portsmouth Harbor on April 19 th 1956. He was generally presumed to have died on a most dangerous underwater assignment, and since that day hundreds of thousands of words have been woven round his name. The last dive is discussed in the last chapter of this book. My hope is that the earlier chapters will provide something of the measure of the man.

MARSHALL PUGH

Prologue KNOW YOUR ENEMY

In December 1941, when the Italians had five battleships in the Mediterranean, the British were reduced to two, the Valiant and the Queen Elizabeth , which lay behind mine-fields and torpedo nets in the inner harbor of Alexandria. At 3.30 on the morning of 19 th December, two Italians were discovered clinging to the anchor buoy at the bows of the Valiant . They were taken ashore for interrogation, and handed over the papers which identified them as Lieutenant de La Penne and Petty Officer Bianchi of the Italian Navy. They declined to give any more information, and were escorted back to the Valiant and held below-decks between the two forward gun turrets. Lieutenant de La Penne remained silent, refusing to be drawn by gibes about the Italian Navy, until 5.45. Then he asked to be taken to Captain Charles Morgan of the Valiant . He said that the battleship was about to blow up, that there was nothing Captain Morgan could do about it, but that he still had time to get his men to safety if he chose. The crew were ordered on deck, the watertight doors of the Valiant were closed. Shortly after six there was an explosion, the battleship reared and the lights went out. The Valiant was temporarily out of the war.

The Queen Elizabeth , lying astern, rose in the water as a second explosion wrecked and flooded her boiler-rooms. A third explosion blew the stern and the propellers from a naval tanker.

In one night six men had swung the balance of sea power in the Mediterranean. They drew a tribute from Churchill to their extraordinary courage and ingenuity.

Thus, he said, we no longer had any battle squadron in the Mediterranean....The sea defenses of the Nile Valley had to be confined to our submarine and destroyer flotillas, with a few cruisers and, of course, shore-based air forces. For this reason it was necessary to transfer a part of our shore-based torpedo-carrying aircraft from the south and east coast of England, where they would soon be needed, to the North African shore.

This victory of six men was not exploited by the Italian Navy as a whole, but it inspired the Tenth Light Flotilla, whose triumph it was.

The Tenth Light Flotilla of the Italian Navy recruited from all three fighting Services and trained their men in two groups.

The Gamma or swimming group wore flexible rubber suits, breathing gear and swimfins. In early training they sometimes marched in Indian file along the sea bed in full war kit. They learned to swim for miles, towing small mines of neutral buoyancy. Once trained, they attached their mines with delayed-action fuses well below the waterline of Allied ships.

The second group manned piloted torpedoes, 14 feet in length, with detachable warheads or explosive noses holding 300 kilograms of explosive. The torpedo was normally launched from a parent submarine. A pilot sat astride it with a diver behind him. The torpedo traveled to the target ship, the diver left his seat, disconnected the warhead and attached it beneath the target with its time-fuse set.

At full speed ahead the machine moved no faster than a walking man. It turned and dived so clumsily that the operators called it the pig. And yet, astride the pigs, they penetrated guarded British harbors in the Mediterranean, making a mockery of torpedo nets and barbed entanglements, of radar and echo-sounders.

Before the attack on Alexandria Prince Junio Valerio Borghese, in command of the submarine Scir , had already made three piloted torpedo assaults on Gibraltar. In October 1940 he passed through the Straits of Gibraltar, turned into the Bay of Algeciras, ran its length submerged and then dispatched three piloted torpedoes from the head of the Bay. Two had to be scuttled, but their crews swam to the shores of Spain, were met by Italian agents and reached home. The third penetrated to the inner harbor of Gibraltar and dived within a few hundred yards of the battleship Barham . The diver ran out of oxygen and had to surface. The pilot steered his machine towards the battleship until it stopped, then attempted to crawl beneath the battleship, towing his torpedo behind him on a length of rope. He was defeated by exhaustion and captured with his diver.

In May 1941 Borghese returned and launched three machines from two and a half miles to the west of Gibraltar. As there were no warships to attack, the pilots set course for merchantmen in the open Roads. When the battery of Lieutenant Vescos machine failed, Lieutenant Visintini towed Vescos chariot behind his own as though a breakdown service were part of the nights work. At last Vescos torpedo was scuttled in deep water, and the two men from it rode the backs of the remaining machines, as third hands. A second machine went down. The three men aboard it swam to the Spanish coast. Visintinis machine pressed on, still with three men up. The first vessel they reached was a hospital ship, the second was Swiss, the third they passed because she was too small. Visintini aimed for a storage tanker. His diver had difficulty fitting the warhead to the target, and as the others tried to help him their machine dived for the bottom. The operators swam to Spain and met Italian agents by arrangement. All six eventually reached Italy.

Next page