Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

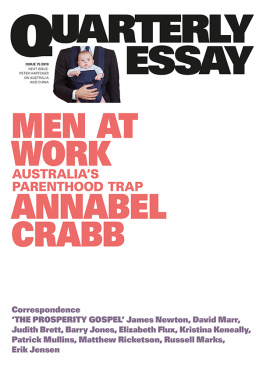

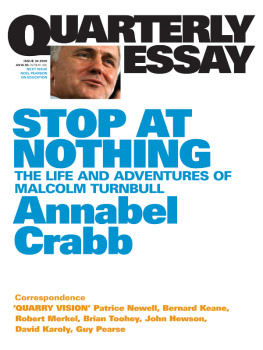

Copyright Annabel Crabb 2009, 2016.

Originally published as Quarterly Essay 34.

This revised edition published in 2016.

Annabel Crabb asserts her right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Crabb, Annabel, author.

Stop at nothing / Annabel Crabb.

9781863958189 (paperback)

9781925203943 (ebook)

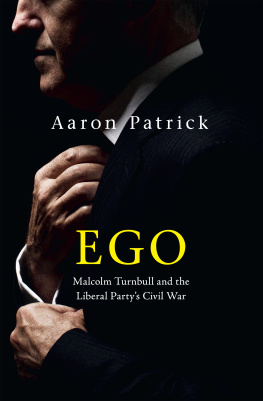

Turnbull, Malcolm, 1954

Liberal Party of Australia.

PoliticiansAustralia.

Prime ministersAustralia.

AustraliaPolitics and government2001

324.29405

Cover image by Louie Douvis

Cover design by Peter Long

Typesetting by Tristan Main

W hen Bruce Turnbull died horribly, shockingly, in a single-engine aircraft that speared to earth in dairy country on the mid north coast of New South Wales it was a ghastly blow to his only son, Malcolm.

Bruce was fifty-six, and had just bought the beautiful Scone cattle farm of which he had dreamed his whole life. Malcolm was twenty-eight, with a newborn baby son.

The universe is fickle sometimes, but for Malcolm Turnbull to whom it had given so parsimoniously in the family department losing a father three months after gaining a son seemed dementedly, pointlessly cruel.

It smashed him up.

Bruces affairs were tangled; properties here and there, and the farm itself was as dry as a twig, with a deep drought underway and urgent decisions to be made about stock, feed and other mysterious agrarian issues far from Turnbulls usual city life at the Sydney Bar.

In a crazy-brave manoeuvre, Turnbull kept the farm. And he submerged his grief in of all things the study of water.

He had always been interested in Roman history aqueducts, and so on, recalls his wife, Lucy Turnbull. He totally immersed himself in the planning of bores and wells. Its really a classic example of how he works.

In the absorbing detail of water tables, aquifers, mineralisation and pipelines, Turnbull found respite from the dragging anguish of bereavement. He loves a knotty problem, and if it involves entering an arcane world of complex widgetry and strange, beautiful words (alluvium, chelation, flocculation, capillarity, miscibility), then so much the better.

Even now, the science of water holds him in a peculiarly tender way.

I remember one day being here with [his son] Al, he says one day when I am at the farm, filming Kitchen Cabinet.

And it was pouring with rain and all the contour banks were full of water and the dams were spilling and the whole place was moving and the water was moving everywhere and I took him and he was just a little boy, you know, with a hat and a little Driza-Bone and we went right up to the top of that hill there and we just walked, we followed the water all the way down and I reckon that was the best lesson you could ever give a boy about hydrology and water and landscape, because he actually saw how it worked. And then we got down to the bottom of that gully, where there is a well. Which is obviously tapping into the groundwater, and we looked down and I could show him the water moving through the groundwater, moving through the well, and come you know flowing into the well from the gravel and aggregate and sand and everything thats around it, so it was ah, just so many memories like that. I love water.

The farm explains a lot about Malcolm Turnbull. Bruce is buried there, under a stone cairn. When he died, Malcolm kept everything. Bruces hat. Bruces boots. Even the stock that local cockies urged him to sell. He wore Bruces watch for years.

But his mother, Coral, is there too. Coral walked out when Malcolm was eight, taking the furniture with her and running away with a new man, leaving her son and her husband in a bare flat. Malcolm was somehow allowed to believe that she was only gone for a while. It wasnt until he flew to visit her in New Zealand and was introduced at the airport to Corals new fianc that the penny dropped. And even then, Malcolm didnt resent her. He still doesnt, even though, in Lucys words, Coral continued to project the most incredible expectations onto her son, notwithstanding her personal absence.

Coral moved to Philadelphia with her new husband in the early 1970s. When, ten or so years later, the husband ran off with a graduate student, Turnbull hoped his mother would move back to Sydney. He bought a house for her in Paddington, which she never occupied, although she visited most years.

She died, in Philadelphia, of bowel cancer in 1991. And her son shipped everything home to Australia.

These days, the Scone farmhouse beautifully renovated by Malcolm and Lucy houses both Bruces things and Corals. All her books are there, and her furniture; even a hall table that still has in a little drawer the Philadelphia trolley-bus tokens she never got around to using.

Its an imperfect reunion; a pale simulacrum of the reconciliation the young Turnbull had hoped for very desperately. But whatever crumbs were left of his parents, he collected tenderly together in the end.

The trolley-bus tokens are heartbreaking, throat-grabbingly so; like watching one of those unbearable nature documentaries about grieving elephants touching their dead babies with their trunks. Theres such an asymmetry of care involved: the child who treasures every scrap of his mother, the mother who squandered years with her son, continuing to demand extraordinary fealty from him despite having done just about everything imaginable to disqualify herself from any such expectation.

And the result: a complicated and fascinating person, who at sixty years of age became Australias twenty-ninth prime minister. A man who has lost power, and gained it, and learnt from both experiences. A man widely known for his vaulting ambition and tooth-rattling tempers, who nevertheless brims with tears at the slightest provocation.

One night at dinner, Turnbull tells a story of how not long after Coral left Bruce took him swimming at North Bondi. Keen for a surf himself, Bruce gave a lifeguard a shilling to keep an eye on young Malcolm, who was barely nine. But the lifeguard lost interest, and Malcolm got into trouble. When Bruce made it back to shore, he couldnt see his son. I remember going under I remember it so clearly, even today, Turnbull recalls. I shouldnt tell this story, because even now it makes me so emotional. And its true, there is a catch in his voice, and as he proceeds, Lucy monitors the situation with her customary cool vigilance.

And to look up, finally, and see him my father coming for me, just powering through the waves I will never forget that feeling.

Hinterland

S omething is missing in Australia. Its been missing since about 9.30 p.m. on 14 September 2015. On that day, one note a deep, rich vibrato that has been a constant part of the rattling, tooting orchestral manoeuvre that is Australian politics for about forty years, sometimes building, sometimes ebbing, but always perceptibly there abruptly stopped. Possibly forever.

What is this missing strain? Its the sound of Malcolm Bligh Turnbull wanting to be prime minister.

Up until that moment, Turnbulls was a life hugely defined by ambition. A life that began in modest circumstances, and was pierced early by maternal abandonment, but picked itself up and became thanks to the efforts of its exuberant, brilliant, changeable occupant extraordinary beyond the aspirations of all but the very few. It is a life that has surged through journalism and activism and business and politics, absorbing literature and art, and intersecting sometimes happily, sometimes unhappily with giants in those spheres.

Next page