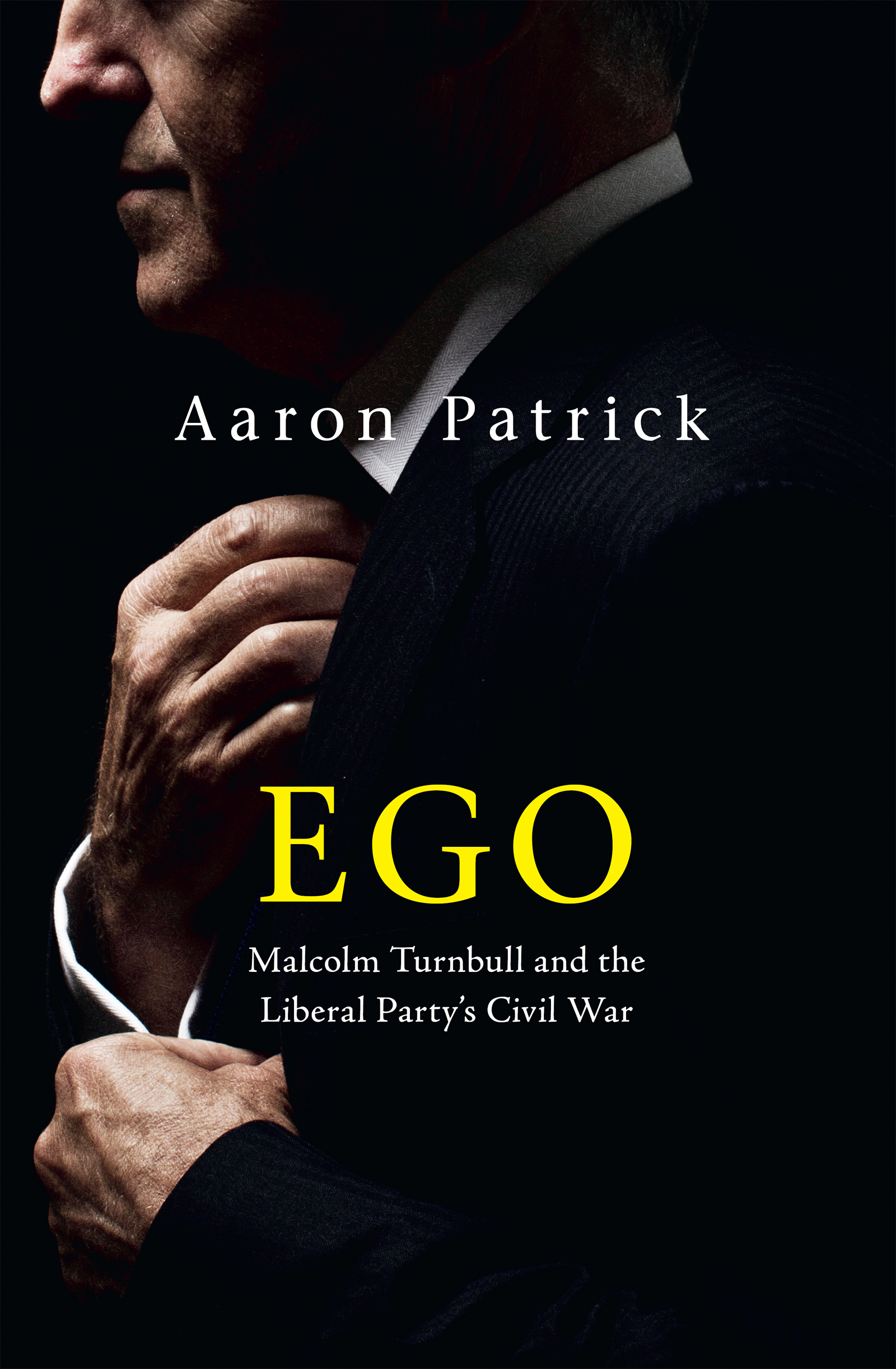

Aaron Patrick - Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Partys Civil War

Here you can read online Aaron Patrick - Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Partys Civil War full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Partys Civil War

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Partys Civil War: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Partys Civil War" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Partys Civil War — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Partys Civil War" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CONTENTS

Malcolm Bligh Turnbull was everything Scott John Morrison was not: erudite, worldly, cultured. Turnbull, a Rhodes Scholar, liked to quote poetry. Morrison, a Pentecostal Christian, preferred the Bible. Once, in parliament, referring to bushfires that ravaged Victoria, Turnbull cited the great Australian poet Dorothea Mackellar, who wrote, We love her beauty and her terror. The quotation was doubly apt, for the devastating power of wildfires and the man who uttered the words.

As Australias twenty-ninth prime minister, Turnbull epitomised missed opportunity. The great promise of Turnbulls leadership was lost in the pointless dissipation of its political capital by decisions not taken on climate policy, economics, technology and social change. Perhaps the only signature social advancement of his government, the end to the prohibition on gay marriage, was achieved in spite of him. The bills sponsor, Warren Entsch, was disgusted when Turnbull supported changes that would have delayed a vote, probably permanently, and then denied Entsch the opportunity to name volunteers in parliament who had spent a decade of their lives fighting for the same right as heterosexual couples.

Turnbull was driven from office on 24 August 2018, not by a conspiracy hatched by alienated conservative colleagues although they were alienated and were conspiring but by his own terror at staring them down. For all his eloquence, sophistication and confidence, Turnbull as prime minister was afraid of intra-party conflict, a fear that would vanish soon after leaving the office he wanted to keep so badly that he was willing to threaten a constitutional confrontation.

In the end, Turnbull was too politically weak to even contest his own leadership. He left office recognised for two non-achievements: squandering the handsome parliamentary majority bequeathed to him by his predecessor, Tony Abbott; and introducing a ban on consensual relationships between ministers and advisers that would do nothing to shield his successor from multiple sex scandals.

Turnbulls humiliation was compounded by what he saw as the calibre of his replacement: a party apparatchik and second-tier industry lobbyist. Worse still, Morrisons persona was a hit in the outer suburbs, towns and country areas that chose the government.

Initially, after the 2019 election victory, the government assumed Turnbull would make peace with his personal loss. Turnbull wished his successor well. He appeared to mean it. Ministers expected their former colleague to adopt the traditional retiring persona of former prime ministers, and, if not support the government, then not actively undermine it. No other Liberal leader, even those who had left the party, had immediately gone to war with it.

Besides, Turnbull seemed more interested in pursuing his predecessor than his successor. He argued that Abbott, the prime minister from 2013 to 2015, led a conspiracy designed to cost the Liberal Party power. Abbotts ambition was to return as opposition leader and try to win government at the following election, Turnbull said. The worst possible outcome for Abbott would be for me to win the 2016 election, he wrote in his memoir, A Bigger Picture. He knew that he wouldnt be elected [leader] again before the election, so his strategy was to continue damaging my government so I that couldnt win.

Turnbull was an atypical ex-politician. One of the richest men elected to Australian office, he had no financial need for the post-political government appointments beloved by most politicians. His media allies were Liberal Party critics. The commentators who attacked him were government sympathisers.

Of Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison, Turnbull was the strongest orator. Abbotts expertise in delivering short quotes for television made voters underestimate his intelligence. Turnbulls struggles to do the same may have led Australians to overestimate his. Either way, Turnbulls authority as a speaker propelled him through four careers: broadcast journalism, the law, investment banking and politics. In the first three, he was able to thrive on raw talent. In the fourth, it got him to the top and then failed him. Ultimately, Turnbull lacked the most important quality needed for leadership: the ability to win his colleagues trust.

Like most of the Australian establishment, Turnbull expected Morrison to lead the Coalition to a convincing loss at the 2019 election. The surprise victory hardened Turnbulls resentment about his own removal. Encouraged to anger by those closest to him, Turnbull sought a form of post-electoral vindication. He openly campaigned against his own party. He promoted the Liberals enemies, attacked their supporters and condemned their policies. He plotted and schemed, applying his enormous energy to the destruction of the Morrison government.

As this book will show, Turnbull participated in the public criticism of several of the Morrison governments greatest challenges after the 2019 election: the historical rape claim against Attorney-General Christian Porter; political adviser Brittany Higginss allegation that she was raped; Education Minister Alan Tudges sexual relationship with his press secretary; the tortuous efforts to formulate an internationally credible climate policy that wouldnt alienate the Coalitions conservative supporters; and Australias diplomatic rift with France over a switch from diesel to nuclear submarines. The Liberal Party had never seen so much naked hostility from a former leader.

Turnbulls influence was broader, though, and reflected a shift in how politics is fought day by day, hour by hour. Turnbulls criticism of Morrisons government turned him into a Twitter hero. He embraced the social media discourse, a digital world where the politically engaged shout at each other and at the public figures they love or hate. At any moment, Turnbull could inject himself into the public debate. The media middleman was removed. A few keystrokes and he was trending.

Some political insiders dismiss Twitter and other social media as fringe fora, unrepresentative of the national psyche. The social media network is a creature of the left, they say, so ideologically driven as to be pointless as a measure of public sentiment or a forum for serious discussion.

Others, including conservatives, acknowledge the reality. The political and media class is addicted to social media. Social media has wormed itself inside their brains, sowing fear of the digital hordes fury and pleasure at their praise. Politicians use Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to blatantly flatter egos. Some, including Josh Frydenberg, a politician who could command access to millions through television cameras almost at will, complain when junior colleagues fail to retweet banal opinion articles written under his name. A few others, including Victorian libertarian Liberal Tim Wilson, fight back, pointlessly arguing with posters who will never be swayed. In newsrooms, reporters, editors and producers obsess over feeds. They look for story ideas, monitor the competition, sample the mood social media is an excuse to avoid the human-to-human contact that uncovers real news, which is information not already public. Mostly, though, they use it to promote themselves. Social media is a semi-legitimate display of narcissism for journalists, placing many at, and often above, the level of the elected representatives who previously dominated political discourse.

Every day, probably every hour, a journalist somewhere conducts a private cost-benefit analysis: will this lead sentence outrage social media or draw praise? Do I dare defy the digital mob today? What angle can I take to attract more followers, the industrys unsubtle measure of influence and popularity? Provided with the intoxicating opportunity of digital fame and unfiltered speech, writers, columnists, reporters, activists and attention seekers, of indiscriminate ideological persuasions and professional experience, have freed themselves from the restraints of impartial argument. On social media, current affairs talk shows and elsewhere, people who should have been guardians of truth turn into propagators of bias. They push agendas inherent in their coverage, whip up outrage and punish counter-narrative proponents. The partisan public, uninterested in the mundane realities of politics, loves them for it.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

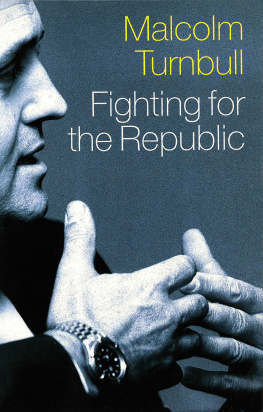

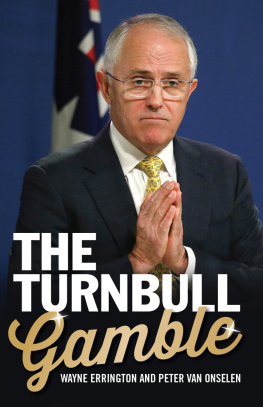

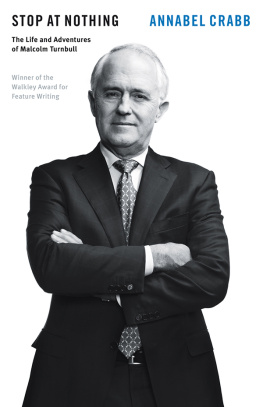

Similar books «Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Partys Civil War»

Look at similar books to Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Partys Civil War. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Partys Civil War and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.