Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Books Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

enquiries@blackincbooks.com

www.blackincbooks.com

Copyright Aaron Patrick 2019

Aaron Patrick asserts his right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

9781760642174 (paperback)

9781743821237 (ebook)

Cover design by Kim Ferguson

Cover photograph by Ryan Pierse / Getty Images

Back cover photograph by Stefan Postles / Stringer / Getty Images

Text design and typesetting by Typography Studio

Prologue

S cott John Morrison held his head up and stretched out his arm, swaying slightly, exhibiting a sense of peace that suggested the singing in the Horizon Church had summoned the Lord himself. On Easter Sunday in 2019, under a sky so clear it verged on the Biblical, Australias fifth prime minister in six years had brazenly permitted himself to be recorded worshipping the supreme being. The hundreds of other worshippers within the auditorium in Sutherland paid no heed to the political deity in their midst. They didnt need to see Morrison to know that he was there; the television cameras trained on their venerated parishioner were enough. They formed a kind of halo around the prime minister, whose very presence was a powerful legitimising force for a young and self-conscious church.

Like the better-known Hillsong church, Horizon is a member of the fast-growing Australian Christian Churches movement, where a literal interpretation of the Bible and peppy Christian songs provide righteousness and family fun every Sunday morning. The churches weirdest belief and theres stiff competition is that speaking in an unintelligible gush of words demonstrates that the Holy Spirit inhabits a persons soul.

Morrisons presence wasnt an affectation. The fifty-year-old had attended Christian camps since he met his future wife at one as a teenager. To the surprise of the media intruders, they had been welcomed in by the churchs married pastors, Alison and Brad Bonhomme, to watch Morrison and wife, Jenny, sing and pray. The political demigod did not object to their intrusive presence, for he had a message for the unblinking eye of the cameras to convey to a nation wary of overt religious belief: this is who I am.

Australias rigorous, if sometimes sacrilegious, democracy had been governed by Protestants, Catholics, agnostics and atheists ever since the days of its first prime minister, Edmund Barton, who conversed in Latin with Pope Leo XIII in 1902. But never before had an evangelical Christian a fellow traveller of deep conservatives like Billy Graham, Jerry Falwell and Mike Pence attained the highest office of state. Even the most spiritual of prime ministers Alfred Deakin, who actually participated in seances declined to invoke the Lords name as frequently as the policemans son from working-class Sydney.

Morrisons calling, so it seemed that day at Horizon, was to unite the Liberal Partys tribes and lead a fatalistic Coalition to an honourable defeat in the nations forty-sixth general election, just under four weeks away. Few in his own party, let alone those engaged in politics more broadly, believed Morrison could beat a Labor opposition so confident that it had proposed one of the most detailed plans for government in Australian history. Morrison had offered his political body to the Liberal Party, and it expected him to be sacrificed on the cross of an electoral loss.

The opposition leader, Bill Shorten, expressed an unwavering certainty that he would vanquish the Coalition government right up to the day voters finally repudiated his 2052 days at the head of the Australian Labor Party. The once great organisation would emerge from his leadership broken and demoralised.

Australians didnt know it as Morrison worshipped that day in an unconventional church, but they were being led by the most underestimated politician since John Howard. His suburban style and overt religious faith would tap into two politically potent currents of Australian society. Three steps forward in his history suggested a man with an exceptional talent for self-advancement. In 2007 Morrison had manoeuvred himself into a safe seat despite the almost universal opposition of local party members; he had then used a bitter leadership change to glide into the second-most powerful job in government; and finally he had replaced the prime minister without initiating a leadership challenge. In his short time as leader, he had demonstrated an adroitness in managing the fractious Liberal Party that exceeded that of his troubled three predecessors, Malcolm Turnbull, Tony Abbott and Brendan Nelson. Now, as he faced the toughest test of all, few believed he would triumph.

Morrisons and Shortens contrasting personas explain a lot, but not all, of the 2019 election result. Morrisons anti-intellectual style and Pentecostal religion were regarded by many Australians as unusual but not inauthentic. Shortens self-publicity machine had carried him from Union Leader With an MBA to Opposition Leader in six tumultuous years. He may have been Australias most overestimated politician since Kevin Rudd. Shortens belief system appeared mutable. His religion, class and ideology were flexible, depending on the situation. A privileged man who loved being a member of the elite became a class warrior who told Australians not to doff your cap to people from the big end of town.

Eleven years earlier, Labor had held power federally and in every state and territory. It could claim to be one of the most successful centre-left parties in the world, and was fulfilling its promise to create a fairer, more tolerant society. By the time Shorten led federal Labor to its third consecutive election loss, on 18 May 2019, his party had been expelled from power in three states where it had once been immovable: New South Wales, South Australia and Tasmania. Federally, the party had held power for just twenty-two of the previous seventy years.

Labor campaigned on what would once have been regarded as the proudest tradition of ambitious policy reform. Shorten promised big investments in health, education and training, to be funded by tax increases on the wealthy. Labor planned to phase out the property tax breaks that had turned many Australians in landlords, and to transform the energy industry from coal and gas to wind and solar. Morrison offered Australians less taxation, a slightly smaller government and no new restrictions on civil liberties or economic freedoms. Given the choice between democratic socialism or the free market with a generous safety net, Australians surprised the political, business, academic and media elites. They voted for Morrison.

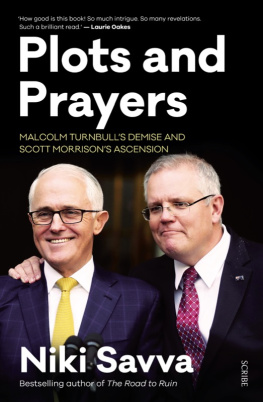

The Coalition won the 2019 election in part because of Liberal Party infighting so severe that its emboldened opponent overreached. The power struggle within the government between Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull, and then between Turnbull and Peter Dutton, was fuelled by unreliable opinion polls that promised an easy Labor victory. Seduced by their expectations of success, Shorten and his team became overly ambitious. At the time, the Coalition was too distracted to effectively attack the big political targets proposed by Shorten. When the Liberals, almost by chance, elected a leader who could unify the party and prosecute a coherent attack, Shorten didnt have the time or political space to moderate his vulnerable policy platform. He was caught in an accidental trap.