TO BELLA, WITH THANKS FOR THE SASS

CONTENTS

T HE REBIRTH OF A government cannot hide the ruthless politics that led to its creation. When Scott Morrison won the election of May 2019, devastating his opponents and stunning some of his own supporters, he described the victory as a moment when his government would come together. What they were coming together from was left unsaid. The government felt its ugly arguments and brutal leadership contests were best forgotten. This was meant to be a unifying triumph for the Coalition, a time to bury the feuds of the recent past.

But no election can wipe away history. The government held on to power but has to live with the jealousies, rivalries and outright hatreds that weakened it before and may do so again.

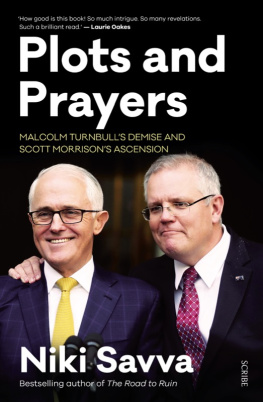

This book is about something that defies rational explanation the wrecking of a government by its own members, almost to the point of total destruction. The lesson is that demolition is easy almost effortless, in fact, when it is done in stages until panic takes hold. The book covers the period from the fall of Tony Abbott as Prime Minister in 2015 to the eruption that toppled Malcolm Turnbull in 2018 and the remarkable recovery once Morrison had assumed control. The book looks forward as well as back, because the Morrison government was formed by forces that can easily return. The divisions among politicians do not end with a leadership ballot or an election.

The tension between private ambition and national interest shapes every event in this book. Two arguments emerge. The first is that no government can deliver stability if it cannot contain the mercenary quests of its own careerist politicians, who know that turmoil brings reward because it removes those ahead of them in the queue for promotion. The second is that mercenary quests are nothing new but become easier than ever in a party room that turns every dispute into a leadership test, when its primary task is to form and hold stable government. Without a change to these incentives, any leader may be doomed.

This book is based on 110 interviews with participants in these events as well as other less formal conversations. It draws on more than 75,000 words in notes and transcripts from these interviews. In establishing key events, I spoke to more than one participant whenever possible, and in some instances heard versions of meetings or conversations which were in direct conflict, in which case I have made this clear to readers. Some of these interviews were conducted on a background basis because the information would only be offered if the source remained confidential. Some interviews were on the record and are quoted. The book also relies on private text and WhatsApp messages between some participants as well as notes of conversations, written personal accounts and documents obtained from various sources.

Politicians guard their memories with care, and some edit their accounts as time passes to be sure they can relive their preferred versions of events. I accept that disputes over parts of my account are certain. New information will emerge over time and the conflict over what occurred will probably never end.

Canberra, June 2019

The images of kings topple before their thrones do.

Peter L. Berger, Invitation to Sociology, 1963

A T THE END OF January 2015, when he had just made one of the biggest mistakes of his career, Tony Abbott telephoned a Liberal Party colleague to try to avert a political disaster. Abbott had been Prime Minister for 500 days and had the status of a conservative hero, one of only four leaders of his party to defeat a federal Labor government and take the Liberals out of opposition and into power in Canberra. Yet his instincts failed him on Australia Day when his love of tradition led him to award a knighthood to the Queens husband, Prince Philip, for his contribution to Australia. It was a catastrophic mistake. Members of Parliament from Abbotts ruling Coalition arrived at Australia Day barbecues and citizenship ceremonies to find voters were mystified at this tribute to the royal family on a day meant to celebrate nationhood. Abbott was mocked without mercy.

In all the ridicule, nothing was more dangerous than the protest from Liberal backbenchers, many of whom already doubted their leaders judgement. Abbott called one of them, Luke Simpkins, in the hope of silencing the howls from party room members already exasperated by his unwillingness to consult on big decisions his captains calls and his handling of unpopular budget savings in health and education.

Abbott got through to Simpkins on the morning of 27 January and was instantly conciliatory. He expressed regret for knighting Prince Philip, explained that he thought it was the right thing to do and admitted it was unpopular. He did not apologise for it. He listened while Simpkins lamented the governments policy confusion and the bad and unpopular honour for the royal family, but there was no way for him to soothe this former ally. My last faith in Tony Abbott was shattered, Simpkins wrote in his personal notes. He was a deeply conservative Liberal but he had given up on the Prime Minister.

The phone call lasted ten minutes. Simpkins ended it by telling Abbott he had to go. The campaign to replace him was underway.

Abbott had bestowed the knighthood with no thought to its political cost. He had received a message from someone he considered a very reliable source telling him the Queen would be pleased if he gave her husband this honour. I gave it twenty seconds thought, he said later, in an interview for this book. Once this information came to me, I thought: Well, thats the end of the matter. If thats what the Queen wants, its a perfectly reasonable request, lets meet it. He did not take the decision to federal cabinet. His own ministers learnt of it through the media. What turned the affair into the trigger for a crisis was not just that he surprised Australians but that he stunned his own colleagues.

No single moment defines a political career, but this marked the beginning of the end for Abbott as Prime Minister and the genesis of the feuds that would destroy the leader who came after him. The rivalries within the Liberal Party turned into lasting enmities once the members of the parliamentary party room put the leadership in play. The shared affliction of these politicians would be revealed over time: chronic disagreement over what they stood for, endless argument over every decision, permanent scheming for personal advancement. The party room, whose stated purpose was to win and hold stable government, became a ferment that never subsided because its volatile chemicals were too combustible when mixed. The hatreds were toxic.

The knighthood only mattered because Abbott was already unpopular with voters and unloved by too many of his own MPs. He had stormed into government in September 2013 after four years as a political killing machine, opposing the Labor administrations of Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard with such ferocity they collapsed into policy disputes and leadership challenges. Abbott was a friend to bishops, an Anglophile with a boxing blue from Oxford, a believer in Western tradition and an implacable opponent of social change. He was expert at applying pressure until his opponents crumbled. He practised his politics with the same unrelenting energy as his daily cycle at dawn to the top of a Canberra hill before attending Parliament.

Abbott could joke about himself with a staccato laugh. As a journalist I was a frustrated politician, he would say. As a politician Im a frustrated journalist. While a trainee priest I was just frustrated. His followers were intensely loyal, yet Australians sensed this man was yearning to govern the country in an earlier age. They saw their suspicions confirmed with his eagerness to restore knights and dames and his willingness to indulge in honours for royalty. Asked to name their preferred prime minister, voters favoured Bill Shorten, who had led the Australian Labor Party since October 2013.