MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

mup-info@unimelb.edu.au

www.mup.com.au

First published 2016

Text Wayne Errington and Peter van Onselen, 2016

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2016

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

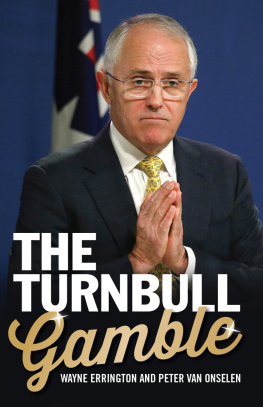

Cover design by Philip Campbell Design

Typeset by Sonya Murphy, Typeskill

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Errington, Wayne, author.

The Turnbull gamble/Wayne Errington; Peter van Onselen.

9780522870732 (paperback)

9780522870749 (ebook)

Turnbull, Malcolm, 1954

Liberal Party of Australia.

Prime ministersAustralia.

Political leadershipAustralia.

AustraliaPolitics and government21st century.

van Onselen, Peter, author.

324.0994

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Malcolm Turnbull was a happy man. Before winning the party-room vote for the leadership of the Liberal Party, he strode confidently down the corridors of Parliament House surrounded by the men, and they were all men, who were about to install him into the leadership. Peter Hendy, Wyatt Roy, Arthur Sinodinos, Mitch Fifield, Scott Ryan and Mal Brough would all be rewarded with promotions in the Turnbull ministry.

Fast-forward to election night 2016. This time Turnbull was surrounded by his family at his harbourside mansion in Sydneys Point Piper. Brough hadnt lasted six months as a minister and didnt recontest his seat after a controversial exit. It was clear on election night that Hendys bellwether seat of Eden-Monaro had gone back to Labor. Roy had to wait nearly two weeks before delivering a classy concession: that he would have time for just being 26. As Turnbull surveyed the wreckage around him, friends had to persuade him to make any sort of election-night appearance. The Liberals federal director Tony Nutt and pollster Mark Textor were with Turnbull, both men frantically trying to confirm whether postal votes would help the Coalition secure a majority. Turnbull wanted to be able to say as much when he fronted the cameras; hence the long wait.

Election-night speeches usually have an audience of millions, although perhaps not by the time Turnbull got to his feet. It was after midnight when he finally took to the podium at Sydneys Wentworth Hotel, and his remarks were not directed to the public who had ridden the roller-coaster of the election count over six hours in lounge rooms and pubs. Turnbulls message was for a much smaller audienceLiberal Party MPs and senators who held his fate in their hands. Turnbull got caught up in the moment, his emotions leading him to ignore the speech his staff had scripted for him, which Nutt and Textor had approved. It was Turnbull unplugged, speaking from the heart. But his heart was black, courtesy of Labors scare campaign on Medicare.

When seats are lost its customary to wish the fallen well. To thank them for their efforts. Turnbull failed to offer such tributes even though he had worked so closely with some of the losers. The set speech contained the necessary words, but Turnbull was off-script. The missing words were a sign that he was not a fully evolved creature of the Liberal Party. John Howard, on the night he lost government and his own seat in 2007, had singled out Mal Brough, who had lost his seat in the Ruddslide. This was instinctive for a career politician like Howard. Not so for Turnbull. We all become somewhat consumed by our own mortality in tough times, but political leaders must rise above their own difficult circumstances.

Its also customary for the leader to take responsibility for the election result. This too was in the scripted speech never delivered. Turnbull, though, tried to deflect blame for the result to Labors systematic, well-funded lies. It was reminiscent of his speech on the night that the republic referendum failed in 1999, when he declared John Howard had broken the nations heart. He looked rattled. Throughout his life he had dealt with failure by blaming everyone but himself and moving on to the next challenge. Yet in both of his efforts as Liberal Party leader, Turnbulls own mistakes largely explain his failures. Bad Malcolm was back.

INTRODUCTION

O N THE NIGHT the Liberal Party voted to depose Tony Abbott from the position of Prime Minister of Australia, one sign of the Turnbull camps confidence was its media strategy. Abbott loyalists desperately visited all the television networks, which had gathered around Parliament House when the coup was announced, singing the praises of their man. Team Turnbull did little other than booking Senator Arthur Sinodinos on 7.30. One issue on 7.30 host Leigh Sales mind was whether Turnbull had changed since his last stint as leader had ended disastrously in 2009. She asked how the party could unite behind Turnbull. This question had also exercised the minds of the leaders of the coup and the MPs worried about their jobs, given the poor standing of their government under Abbott. Malcolm has promised to have a more consultative style, to reach out to people, Sinodinos argued.

Hes had now virtually six years to reflect on the weaknesses and drawbacks of his first period of leadership, just like John Howard did when he lost in 89 and came back to the leadership in 95. Leaders reflect. They understand the messages from their first term as leaders and they try again.

Given the scale of his previous failure as leader, Turnbull would have had to have changed a lot to salvage the wreckage of the Coalition government.

Replacing even an unpopular prime minister was a gamble just a year from an election. Did Turnbull underwhelm so many observers because expectations were too high, or was his chief backer Sinodinos wrong when he claimed Turnbull had learned from past failures and re-emerged a new man, like John Howard had in 1995? Perhaps the gamble was doomed from the beginninga public angry at Abbotts lies may have been unwilling to take his successor on trust. The positive public response to Abbotts removal suggests that voters were relieved when he was gone, even if the costs of change were yet to sink in. The costs of removing a first-term prime minister can be papered over for only so long, and resentment among some conservatives soon emerged. Turnbull discovered that he had taken over a party without a battle plan for the looming election, with little or no money set aside to fight a campaign. The unions were always going to strongly support a Labor Party led by one of their own, Bill Shorten.

The Turnbull gamble had one requirement for successwinning the 2016 election. Had the Coalition won as a minority government, as many predicted on the evening of the count, the gamble would have come under much more criticism. The final result, holding government with a small majority of seats that could disappear due to death or misadventure, may only delay the reckoning for Turnbull and those who installed him. The term Pyrrhic victory refers to two battles against the Romans during the Pyrrhic Wars thousands of years ago. King Pyrrhus suffered such casualties that, according to Plutarch, one other such victory would utterly undo him. This may turn out to be Turnbulls predicament following his victory on 2 July 2016. A huge loss of seats, greater dependence on the National Party, a Senate worse, perhaps, than the one that came before it, a feral conservative commentariat still furious about Abbotts removal, and divisions and distrust in sections of the parliamentary ranks. This is the outcome of the 2016 election, including the return of Pauline Hansons One Nationthe antithesis of Turnbulls metropolitan liberalism. At times in the weeks following the election we needed reminding that Turnbull did in fact win, giving him a chance to prove himself as a prime minister with a public mandate for his prime ministership, if not for far-reaching policy reform.

Next page