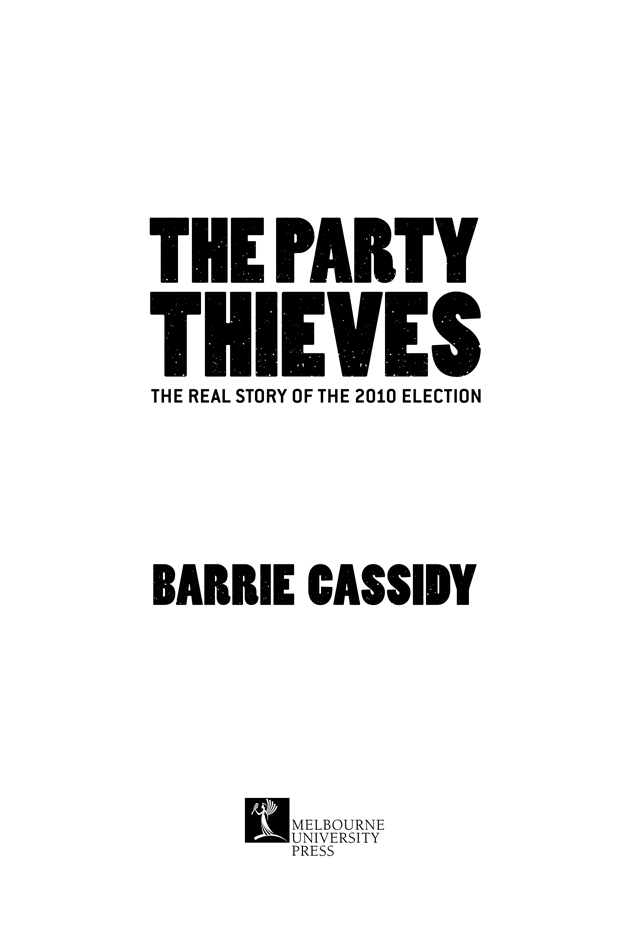

Preface

When I was first approached to write a campaign diary on the 2010 federal election in November 2009, I hesitated. How much interest would there be in a book recording the re-election of the Rudd Government, probably with an increased majority?

Then the Australian political world turned upside down. The drama that took place from December 2009 to August 2010 has to rate as one of the top political events of the last fifty years, right up there with the dismissal of the Whitlam Government, the disappearance of Harold Holt, and the day Malcolm Fraser called an election as Labor changed leaders, swapping Bill Hayden for Bob Hawke.

First, in December 2009, the charismatic and free-spirited Malcolm Turnbull lost the leadership of the Liberal Party to a pugnacious former amateur boxer, Tony Abbott, after a ballot that captivated a nation because of its uncertainty. Nobody knew for sure which of three menTurnbull, Abbott or Joe Hockeywould win. In the end, Turnbull lost by one vote in the final count, and Hockey effectively by just two voteshad Hockey survived the first round, he surely would have won the run-off.

With Turnbull gone, Abbott was free to attack Prime Minister Kevin Rudd over his great big new tax to counter climate change. Luckily for Abbott, within the space of five months, Rudds extraordinary popularity would go into freefall, culminating in the loss of a million votes in two weeks when he walked away from an emissions trading scheme in April 2010.

Rudd would go the way of Turnbull in June, cut down, far more comprehensively, by rank and file MPs. As a result, Australia had its first female Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, a Welsh migrant and declared atheist with no children and a live-in partneras if such a dramatic political tale needed an historic footnote.

On reflection, both Turnbull and Rudd had stolen their parties. In Turnbulls case, it was because of a manic desire to get his own way, because of his refusal to compromise on climate change when the majority of his own party were deeply disturbed about the prospect of an ETS, and because he simply stopped listening to them. Rudd had done so through his authoritarian approach: the more his popularity soared, the more he ruled alone, taking only sycophantic advice and being answerable to no onenot the party, the executive, the Cabinet or the Caucus. MPs complained they were either ignored or abused. The Cabinet became a rubber stamp for a gang of four ministers.

In both cases, the MPs came at the party thieves and took their parties back. That process eventually pitted Julia Gillard against Tony Abbott in the countrys tightest-ever federal election. Neither of the major parties secured a majority of seats, resulting in the first hung parliament since World War II.

For seventeen days after the election, the country was in political limbo as the major parties courted the independents for their crucial support. Then, on Tuesday 7 Septemberfifty days after the election was first calledJulia Gillard managed to form a minority government by the narrowest possible margin.

The longest campaign, as Tony Abbott had called it, was finally over.

1

Kevin 07

When Mark Latham trashed the Labor Party vote at the 2004 federal election, and then imploded afterwards, Kevin Rudd saw his first real opportunity to lead. The party was shell-shocked after receiving just 37.6 per cent of the primary vote, the lowest since 1931. John Howarda man Labor despised and chronically underestimatedhad prevailed again and was now well on the way to establishing himself as one of the countrys most successful prime ministers. Latham had proved to be erratic and unstable; leading lights like Julia Gillard had shown poor judgement in ever believing he was the answer to the partys malaise.

After the election, Latham sulked for a few months, then quit. He had suffered another painful bout of pancreatitis and gone off to Terrigal, on the NSW Central Coast, over the Christmas break to recover. While he was there, one of the worlds worst ever disasters hit the Pacific rim from Indonesia to Sri Lanka, erasing whole communities and killing more than 225 000 people. But there was not a word on the tsunami from the Leader of the Opposition.

When he finally emerged, the scene was both comical and bizarre. Latham had given the media less than one hours notice that he was giving a press conference near his home at tiny Hallinan Park. As he got out of his private car, the media was still running in from all directions, trying to set up in time. Latham, sporting a new and striking close-cropped haircut, announced his resignation by reading a short statement from a sheet of paper. Then he turned on his heels and left.

The Labor Partys choice then was to return to Kim Beazley, who had at least once outpolled Howard on the raw numbers, or turn to the next generation represented by Julia Gillard and Kevin Rudd. But unlike the situation almost three years later, Gillard and Rudd were not about to cooperate simply to bring Beazley undone. Because neither was prepared to give up their numbers to the other, Beazley emerged as the only option.

From then on, however, Rudd worked tirelessly to build up his credibility and his profile. As shadow minister for foreign affairs, he relentlessly and ruthlessly went after the Howard Government and its foreign minister, Alexander Downer, over the Iraqi wheat scandal. The Australian Wheat Board had been accused of paying Saddam Husseins regime transport fees, or kick backs, to boost exports. No impropriety by government ministers was ever proven, but Rudd managed to create a cloud of suspicion by sheer intent.

He gradually built up a network of media contacts in the press gallery and beyond, from conservative columnist Piers Akerman to the ABCs late-night broadcaster, Phillip Adams. He once phoned me asking whether I could persuade Kerry OBrien to have him on The 7.30 Report more often; he managed to do that without my help, through sheer persistence. He wrote two long essays for The Monthly , examining everything from the role of Christianity in politics to Howards Brutopia, the latter a thesis on the emergence of market fundamentalism and the role of workers as little more than pawns in the production process. The essays gave the ALP a fresh voice and caused the latte set to swoon.

But his great coup was to land a regular spot debating Joe Hockey on Sevens Sunrise program, reaching a wide audience of ordinary Australians. The program gave him a platform to comment on absolutely everything. Not only did he cleverly exploit a softer approach to politics and display a folksy side to his personality, but he established an important relationship with one of the programs hosts, David Koch, which served him well for years. He walked the Kokoda Track with Hockey and Koch, winning invaluable exposure along the way. He was no more popular with his colleagues, but they did come to admire his spirited and well-researched parliamentary performances.

Through 2005 and early in 2006, Beazleys numbers held in most opinion polls, but internal research confirmed why his colleagues felt uneasy nevertheless. Essentially, voters had stopped listening to him. He had been around the block once too often and, as such, he did not present as a viable alternative to the Prime Minister, even though Howard was vulnerable for the same reason.

In the second half of 2006, Gillard and Rudd secretly and loosely agreed that Beazley should go, and that Gillard would come in behind Rudd. Gillard had about 40 per cent of the Caucus votenot enough, but far more than Rudd. However, she judged that Rudd was more advanced and better prepared at that stage, both in a personal and a policy sense, to take the fight up to Howard and present as a ready-made replacement.