This edition copyright A Vincent McInerney 2013

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978 1 84832 164 9

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47382 154 5

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47382 250 4

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47382 202 3

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopying, recording,

or any information storage and retrieval system, without

prior permission in writing of both the copyright

owner and the above publisher.

The right of Vincent McInerney to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Typeset and designed by M.A.T.S. Leigh-on-Sea, Essex

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, Wiltshire

Editorial Note

MAN-OF-WAR LIFE was published in 1855 by Dodd, Mead & Company and it is this edition that has been used for the present abridgement; it was Nordhoffs first book and covered his years at sea in the US Navy from 1845 to 1847. In 1847 he joined the merchant service and went on a number of voyages to Europe and the Far East before becoming involved in the whaling and fishing industry in New England. He left the sea behind in 1854 and, aged just twenty-three, took up journalism which he pursued until his death in 1901. During that period he was an editor on Harpers Weekly, the managing editor of the New York Evening Post, and the Washington correspondent of the New York Herald. He was a strong supporter of the Union cause during the Civil War and he was to become one of the most well known American journalists in the latter years of the nineteenth century.

Man-of-War Life was a success and was to go through a number of editions. The second edition, published in 1883 with a new preface, also contained illustrations that the publishers believed would entice a new readership. The initial success of the first edition encouraged Nordhoff, and in 1885 he wrote The Merchant Service, which compared his experiences on a trading vessel with his years in the navy; he had found the life of a merchant seaman, despite the freedoms, to be a lot tougher than the life of a bluejacket in the navy. This was followed in 1856 by Whaling and Fishing and in 1857 with Stories of the Island World.

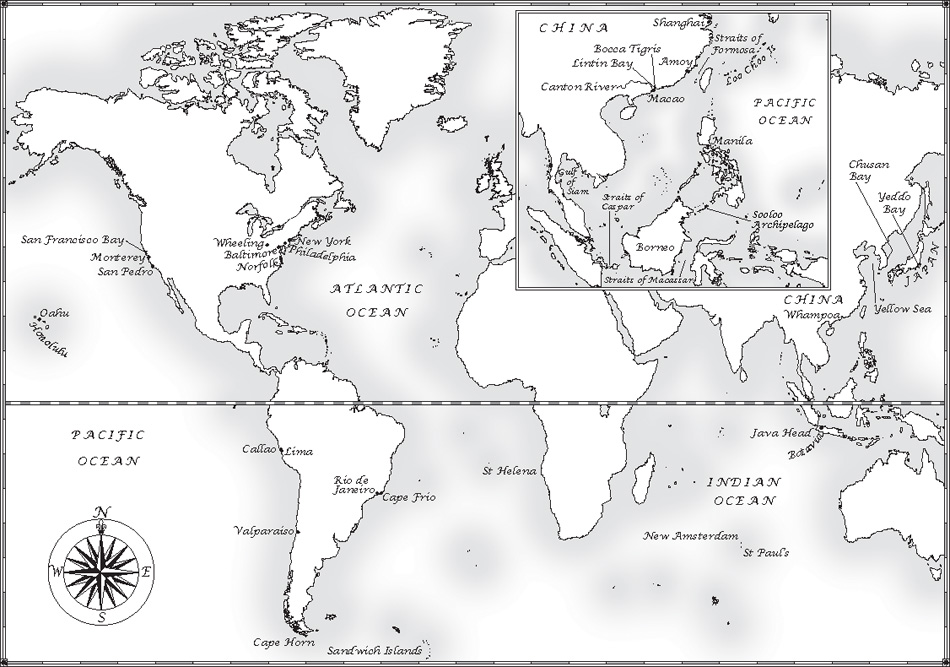

Man-of-War Life, with its vivid and authentic descriptions of naval life, found an enthusiastic audience, but historians have since found it also a useful account of Commodore James Biddles successful negotiations with China to establish diplomatic relations. This aspect of voyage was not something that really registered with the young Nordhoff, but nonetheless the very personal account contains much that illuminates the official aspects of the Columbus cruise to the Far East. For the modern reader though this finely written account shines its sharp light most brilliantly on the now vanished way of life once so common on the noisy decks of a sailing warship.

Introduction

A trained seaman is a respectable person. He is a good deal of a boy ashore; he probably gets drunk when liquor comes in his way; he may even come aboard drunk; but he is brave; has a strong sense of duty; and so great a pride in his profession that he is usually something of a pedant, for he is apt to think that the man who can hand, reef, steer, and heave the lead, is the best of created beings. But as he has travelled he is sure to have some intelligence, and a good knowledge of men, which gives him tact.

CHARLES NORDHOFF wrote what is possibly the most detailed account of daily life on board an American man-of-war in the mid nineteenth century. In 1845 he signed as a First-Class Boy in the USS Columbus, a large 74-gun ship of the line that had been chosen to undertake a diplomatic mission to China and establish relations with Japan. He paid off in the same capacity almost three years later having circumnavigated the world, and the resulting book, Man-of-War Life, is an extraordinarily vivid account of the daily life of the ordinary seaman. As he wrote in the Preface of the first And indeed it is the lack of any romanticism that adds such value to the work as a record of sailors lives in the last days of sailing navies. The memoir is a masterpiece of unvarnished description that perhaps tells better than any other the real nature of life below decks in a man-of-war.

Charles Nordhoff was born in Erwitte in Prussia in 1830, and emigrated to the United States with his parents in 1835. He was educated in Cincinnati: being a regular book-worm I went to school until I was thirteen. Then, by my own choice, I became apprenticed to a printer. Printing, and the conditions under which it was then practised, began to affect Nordhoffs health. Looking for a remedy, and his reading having covered many volumes of travel, he decided that going to sea would effect a cure. This was a solution to bodily and mental ills that was chosen by many young men, often middle-class, who envisaged the beneficial effects of warmer climates, the stimulation of changes of scene, and the curative benefits of hard manual work. R H Dana in Two Years Before The Mast wrote that I determined to undertake the voyage to cure, if possible, James Johnston Abraham, in The Surgeons Log, leaves a memorable picture of waiting to join his first ship. Abraham, verging on a complete nervous breakdown from overwork in London hospitals, signed with Blue Funnel, and was recommended a Birkenhead sailors hotel while waiting for the Clytemnestra.

I walked into a room I thought was public to find I had invaded a den of retired sea captains. Curious shells and carvings faded photographs A painting of a fully rigged ship on carefully regulated waves. Although all were friendly, my pale student complexion and washed-out appearance excited little comment For here they were well used to wrecks of men returning from the fever-zones of the Amazon, West Coast of Africa, the Malay Archipelago.

Nordhoff, at thirteen, and with twenty-five dollars, left home and headed for Baltimore to try for a vessel. Constanly rebuffed, and with only two-and-a-half dollars left, he made for Philadelphia having read of the kindness of the Quakers. Again unsuccessful, he returned to printing, gaining a post on the Philadelphia Daily Sun as boy of all work, thanks to its editor, Levin, who also found him lodgings.

He continued to haunt the docks, but became convinced that he would never find a ship in the merchant service unaided by outside influence as merchant ships carry no more cats than can catch mice, and if a boy is needed the captain will opt for a runaway English apprentice, because although in general far less intelligent than American lads, they are inured to labor and hardship, and, consequently, much more useful.

It is then that Nordhoff learns of the USS Columbus (74 guns) being commissioned for a voyage to China and Japan, with hands being shipped at the Naval Rendezvous, but he is told that having no parent or guardian, he can only be shipped by a special order from Commodore Elliott (Commandant of the Navy Yard). Levin, a friend of Elliott, intervenes on his behalf and eventually Elliott writes the chit that provides his entry into the United States Navy that same day, Nordhoff signing as a First-Class Boy at wages of eight dollars per month.