About the Book

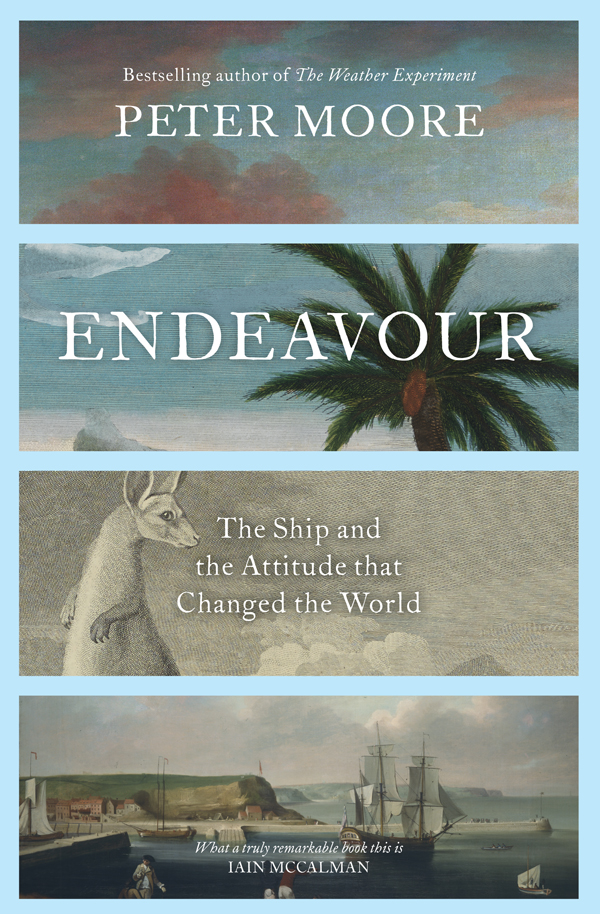

The Enlightenment was an age of endeavours. From Johnsons Dictionary to campaigns for liberty to schemes for measuring the dimensions of the solar system, Britain was consumed by the impulse for grand projects, undertaken at speed. Endeavour was also the name given to a Whitby collier bought by the Royal Navy in 1768 for an expedition to the South Seas. No one could have guessed that Endeavour , a commonplace, coal-carrying vessel, would go on to become the most significant ship in the history of British exploration.

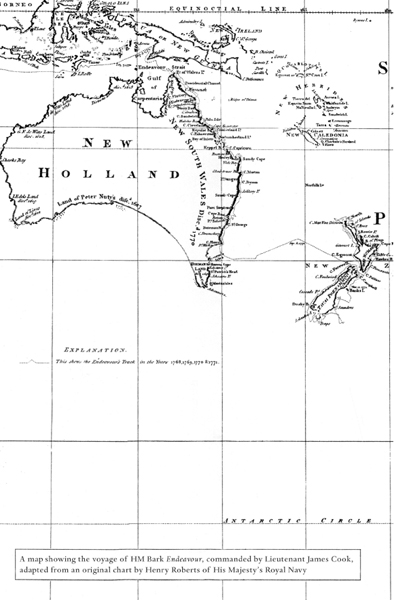

Endeavour famously carried Captain James Cook on his first great voyage, visiting Pacific islands unknown to European geography, charting New Zealand and the eastern coast of Australia for the first time and almost foundering on the Great Barrier Reef. But Endeavour was a ship with many lives. She was there at the Wilkes Riots in London in 1768, and during the battles for control of New York in 1776, she witnessed the bloody birth of the United States of America. As well as carrying botanists, a Polynesian priest and the remains of the first kangaroo to arrive in Britain, she transported Newcastle coal and Hessian soldiers. According to Charles Darwin, she helped Cook add a hemisphere to the civilised world. NASA named a space shuttle after her. To others she would be a toxic symbol, responsible for the dispossession of the oldest continuous human society and the disruption of many others.

No one has ever told Endeavour s complete story before. Peter Moore sets out to explore the different lives of this remarkable ship and her rich and complex legacy.

It is pleasing to contemplate a manufacture rising gradually from its first mean state by the successive labours of innumerable minds; to consider the first hollow trunk of an oak, in which, perhaps, the shepherd could scarce venture to cross a brook swelled with a shower, enlarged at last into a ship of war, attacking fortresses, terrifying nations, setting storms and billows at defiance, and visiting the remotest parts of the globe.

Prologue: Endeavours of the Mind

In February 1852, the British writer John Dix stepped on board the Empire State , a steamship bound from New York to Newport, Rhode Island. About forty years old, Dix had spent several years roaming across the United States, scenting out colourful stories that he could write up as travel sketches. Many of these were printed in article form by the Boston Atlas , while collections were packaged together and sent back to Britain under the byline A Cosmopolitan or, enticingly, an eminent literary gentleman on the other side of the Atlantic.

Dix had spent the winter in Brooklyn, New York. A tireless wind had blown south from the Great Lakes, cutting about the shoulders of walkers on the street. For the second consecutive year the East River had frozen, becoming a carpet of ice that capped the black waters where the herrings and harbour seals swam. Several brave souls had ventured across to Manhattan Island, that great wilderness of marble and mortar, the abode of merchant princes and millionaires.

Only in late February were the biting northerlies replaced by the soft thaw winds of spring. It was around then that Dix read in a New York paper that the ice in Long Island Sound was breaking apart. At last presented with a chance of escape, Dix had walked to the harbour and purchased a ticket to Newport. His plan was to seize the earliest opportunity of visiting a friend in the coastal state and, hopefully, root out some fresh copy. At four that afternoon, as the sun was sinking behind the Hudson, he heard the merry chime of the pier bell. A loud twang rang out from the Empire State s engine room, a puff of black smoke filled the air, and, almost noiselessly, the huge double-chimneyed vessel glided from the shore.

Dix had come to America to start anew. His promising early career in literary London launched by a heart-touching biography of the child poet Thomas Chatterton had been blemished by addiction to alcohol. This vice had cost him friends and injected an erratic quality into his journalism, bringing him a reputation as a fabulist. His revival had begun well. In the United States he had embraced the temperance movement and exploited his position as an outsider, casting a wry English eye over a youthful nation. In 1850 he had published Loiterings in America and in early 1852 was embarking on a fresh collection of travellers tales. This would turn out to be a compendium of American scenes, accounts of hearing Daniel Webster address 100,000 in Philadelphia (he forcibly reminded me of Sidney Smiths pithy description of him a steam engine in breeches); a trip to Connecticut, the Yankee state par excellence , to meet Samuel Griswold Goodrich; then an interview with Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Toms Cabin a book so successful, Dix estimated, that sales in its opening nine months had outstripped those of Waverley , The Sorrows of Young Werther , Childe Harold , The Spy , Pelham , Vivian Grey , Pickwick , the Mysteries of Paris and Thomas Babington Macaulays History of England put together.

All this lay ahead as the steamer ploughed through Long Island Sound. The Empire State was a paragon of modern luxury, as different from the old square-rigged sailing ships as could be. Not two decades before Charles Darwin had been forced to tolerate the conditions on HMS Beagle : the nauseating swinging and jerking of his hammock, the decks and hatches beating and pattering with feet, the reek of turpentine and tar. Now Dix was allotted his own apartment, furnished with sofas, ottomans, chairs and marble-covered tables. In the saloon a lady played piano while a gentleman sang in accompaniment. I never should have dreamed that I was afloat on the ocean wave, Dix wrote. To him the steamers were indeed floating Hotels! From the barbers shop to the bed all is perfection.

A day later Dix was ashore at Newport. The climate, he decided, reminded him of the Isle of Wight. Newport was an old town nestled within the complex geography of Narragansett Bay. The bay a vast expanse of water dotted with islands the locals used as stop-offs on fishing trips was once of strategic consequence, but over the last decades Newports significance had dwindled. Trade had moved north to Providence, and what life remained blossomed only briefly. Only once, during the year, does the old town show any signs of vitality, and

Out of season and with little to entertain him, Dix strolled over the town. He found a curious old mill and several unusual rock formations in the cliffs. Investigating one he discovered many spires of stalactites, forgotten fingers of frozen water that brought to mind the glittering palaces of the Arabian Nights. But Dix was to find his best story at the wharves. There he fell into conversation with an English gentleman. After talking for a time this man surprised him by revealing a very interesting naval relic was standing in a store hard by. He led Dix to the counting house of an oil merchant. There the man pointed out an apparently mundane object: a large wooden post, splintered and wizened but still upright and entire.