Contents

About the Book

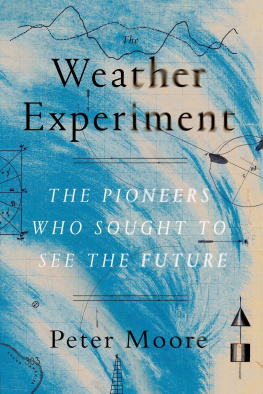

In 1865 a broken Admiral Robert FitzRoy locked himself in his dressing room and cut his throat. His grand meteorological project had failed. Yet only a decade later, FitzRoys storm-warning system and forecasts would return, the model for what we use today.

In an age when a storm at sea was evidence of Gods great wrath, nineteenth-century meteorologists had to fight against convention and religious dogma. But buoyed by the achievements of the Enlightenment a generation of mavericks set out to explain the secrets of the atmosphere and learned to predict the future. Among them were Luke Howard, the first to classify the clouds, Francis Beaufort who quantified the winds, James Glaisher, who explored the upper atmosphere in a hot-air balloon, Samuel Morse whose electric telegraph gave scientists the means by which to transmit weather warnings, and FitzRoy himself, master sailor, scientific pioneer and founder of the Met Office.

Reputations were built and shattered. Fractious debates raged over decades between scientists from London to Galway, Paris to New York. Explaining the atmosphere was one thing, but predicting what it was going to do seemed a step too far. In 1854, when a politician suggested to the Commons that Londoners might soon know the weather twenty-four hours in advance, the House roared with laughter.

Peter Moores exhilarating account navigates treacherous seas, rough winds and uncovers the obsession that drove these men to great invention and greater understanding.

About the Author

Peter Moore is a writer, freelance journalist and lecturer. He teaches creative non-fiction at City University and lives in London. His first book, Damn His Blood, an acclaimed history of a rural murder in 1806, was published in 2012. www.peter-moore.co.uk. @petermoore.

Also by Peter Moore

Damn His Blood: Being a True and Detailed

History of the Most Barbarous and Inhumane Murder at

Oddingley and the Quick and Awful Retribution

Illustrations

Unless otherwise stated, images come from the authors private collection.

Illustrations in the text

. Richard Lovell Edgeworths telegraph, 1830.

. Claude Chappes telegraph, 1794 ( The British Library Board, 2394.f.3 p33).

. Cloud formations above a rural landscape, with a key to the types. Engraving by E. Radcliffe ( Wellcome Library, London).

. Sketch from Researches about Atmospheric Phaenomena, by Thomas Forster, 1816.

. Engraving from A Voyage Towards the South Pole, performed in the Years 1822 1824 , by James Weddell ( The British Library Board, G2558 between p3435).

. Map of South America by Robert Wilkinson, 1813.

. A combined thermometer, hygrometer, and barometer. Engraving after B. Martin ( Wellcome Library, London).

. The distressed situation of His Majestys Ship Egmont in the West Indies hurricane of 1780 (PX8417 National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London).

. Samuel Morse making his experiments with telegraph transmission ( Wellcome Library, London).

. Samuel Morses telegraphic language ( The British Library Board, 1398.f.24 p27).

. Cecilia Glaisher snow crystal designs, 1855 ( The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge).

. London from Blackheath, Illustrated London News, 1846 (with thanks to the Gladstone Library for permission to reprint).

. Cecilia Glaisher snow crystal designs, 1855 ( The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge).

. Royal Charter Wreck, Illustrated London News, 1859 (with thanks to the Gladstone Library for permission to reprint).

: Synoptic chart of the Royal Charter Gale, 1859, from The Weather Book, by Robert FitzRoy, 1863.

. Cone signals, Illustrated London News, 1860 (with thanks to the Gladstone Library for permission to reprint).

. James Glaishers instruments deck in the hot-air balloon, from Travels in the Air, by James Glaisher et al, 1871.

. The Pigeons, from Travels in the Air, 1871.

. Flight profile of a balloon ascent in 1862, from Travels in the Air, 1871.

. Air temperature observed in the balloon ascent and descent in 1864, from Travels in the Air, 1871.

Plate Section

1. Portrait of Robert FitzRoy, c.1831 ( Science Photo Library).

2. Study of cirrus clouds by John Constable, c.1821/2 ( Getty Images); Spring: East Bergholt Common, by John Constable, c.1814, 1821 or 1829 ( Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

3. Mount Sarmiento, Tierra del Fuego, showing the survey ship HMS Beagle (PW6229 National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London); a meeting of the Royal Society at Somerset House ( The Royal Society).

4. Men of Progress, a group portrait of the great American inventors of the Victorian Age, by Christian Schussele, 1862 ( Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C./Bridgeman Images); the Arctic Council planning a search for Sir John Franklin, by Stephen Pearce, 1851 ( De Agostini Picture Library/Bridgeman Images).

5. (clockwise from top left) Robert FitzRoy, c.1864 ( Royal Astronomical Society/Science Photo Library); James Pollard Espy, by Thomas Sully, 1849 ( Photo National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian/Art Resource/Scala, Florence); Sir Francis Galton by Gustav Graef, 1882 ( National Portrait Gallery, London); James Glaisher c.1860s.

6. Mirage and Luminous Aureola from Travels in the Air, 1871.

7. Isothermal Chart, or View of Climates & Production from William C. Woodbridge, school atlas, published by Oliver D. Cooke & Co., Hartford, 1823 (Graphic Arts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections Princeton University Library); Chart of the Christmas Day snowstorm in 1836, by Elias Loomis, 1859 ( The David Goldsmith Collection).

8. Tropical and polar air current, from The Weather Book, 1863.

To my mother

The Weather Experiment

The Pioneers who Sought to See the Future

Peter Moore

A fool, you know, is a man who never tried an experiment in his life.

ERASMUS DARWIN TO RICHARD LOVELL EDGEWORTH

We see nothing truly till we understand it.

JOHN CONSTABLE

The Weather Clerk himself, after a life of practice, as well as study, values the forecasts more and more as a scientific ground on which to hoist the drum.

ADMIRAL ROBERT FITZROY

The Weather Experiment

WE ARE NEVER far from a weather forecast. An average Briton on an average day might encounter five or six of them, broadcast, printed, tweeted, passed on second hand. You can wake in the morning to the sparkling enthusiasm of a breakfast weather presenter, and be lulled off at night to the mantric rhythms of Radio 4s shipping forecast and its signature tune, Sailing By.

Whatever the medium, the weather forecast is an ingrained component of modern life, its ever-evolving projection of what the atmospheres got in store always at hand. As a rule forecasters are clean-cut, bright-eyed, full of empathy and concern when something grim is on the way. The kind tenor of their broadcasts, the sharp suits, the mild manners, the crisply delivered chunks of meteorological caution can fool you into thinking they are paragons of conservatism. The reality is completely different. These forecasters are in fact the product of one of the most notorious and daring scientific experiments of the nineteenth century.

It is a strange thought. Such is the ubiquity of the forecast today it is difficult to imagine an age before it existed. The bright, breezy afternoon of 24 November 1703, for example, when the Great Storm the most intense ever to strike England was hurtling wolf-like towards the west coast. Hardly anyone could have foreseen what was about to happen. Winds stripped lead from church roofs, windmills were blown with such force that they spun into flame like giant Catherine wheels. Cattle and sheep were swept over hedges. Ships were blown across the North Sea from Harwich to Sweden, and others were driven on to the Goodwin Sands where an estimated 2,000 were swallowed up by the waves. No final tally was recorded but it is thought 10,000 died in a handful of hours. For Daniel Defoe it was a disaster far worse than the Great Fire of London.

Next page