Table of Contents

Making Sense of Weather and Climate

MARK DENNY

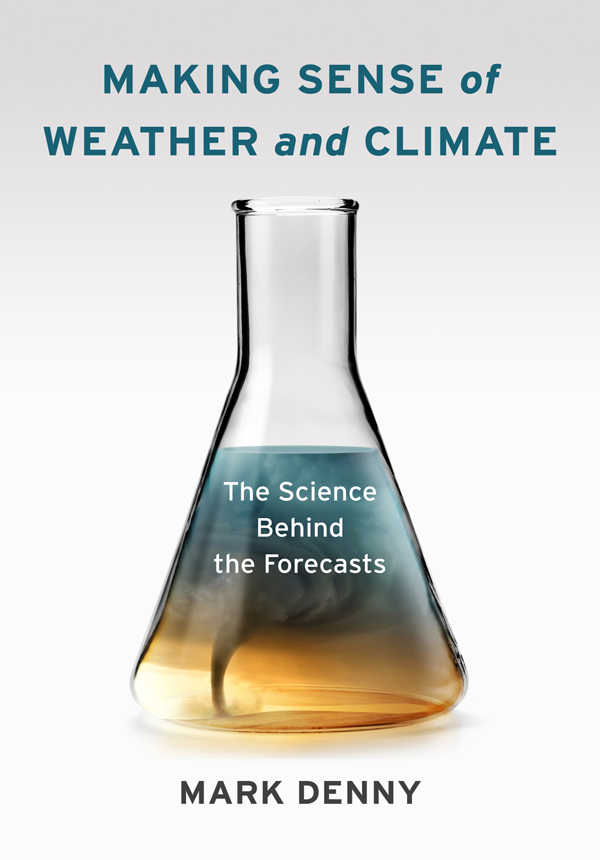

Making Sense of Weather and Climate

The Science Behind the Forecasts

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2017 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54286-9

ISBN 978-0-231-17492-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-54286-9 (e-book)

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress.

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

COVER DESIGN: Diane Luger

COVER IMAGE: Chemical glass flask ( Dollar Photo Club); Olexander, Sunset tornado ( Dollar Photo Club / James Thew)

Contents

One of the issues that arises when writing popular science books is that of units. Yards or meters? Kilograms or pounds? In everyday life, we use both. However, mixing units is considered uncool in the scientific community, though it happens often enough, and so in Forecast, I offer a sheepish apology for this misdemeanor. (In fact, I use metric units with more familiar units added parenthetically, where they are needed.)

References are a mixture of primary sources, which can be very technical, and secondary or educational material, which may be more suitable for the nonspecialist. The former are included mostly to provide backup for the claims made in the text, and for readers who want to dig much deeper into weather and climate physics; the latter are further reading for those who wish to delve only a little deeper into our subject. The notes point you to the references but do much more than that, so please read them.

Reading over the manuscript, I note quite a few statements of the kind As we will see in chapter X and As we saw earlier. I appreciate that such temporal cross-referencing can be a little irritating to some readers, but it is unavoidable in subjects that are as intertwined and multifaceted as meteorology and climatology. Similarly, there are subjectsthe Coriolis force is onethat are raised more than once, in different chapters. This is also due, in part at least, to the interconnectedness of matters meteorological and, in part, as a pedagogical device.

Writing this book has occupied something like a year of my working life. It required much organizing and reorganizing, explaining and rewriting, reviewing and reviewing again. I am grateful to Patrick Fitzgerald and Ryan Groendyk of Columbia University Press for their encouragement and support during this intense process. Thanks to Irene Pavitt, at Columbia University Press, and to Terry Kornak for turning the manuscript into a book. For his technical help, I am grateful to meteorologist Chris Wamsley of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Finally, I thank Thomas Birner of Colorado State University for his very detailed, constructive, and helpful review of the first version of the manuscript. Any errors that remain are mine alone.

Its so dry the trees are bribing the dogs.

Charles Martin

The book that you hold in your hands will help you make sense of our weather. My aim in writing such a book is, as always, to provide transparent science that conveys the core ideas underpinning a complex physical systemin this case, the physics of our atmosphere. This book will also help you make sense of our climate (so extending the physics to our oceans) and how we model and predict climate and influence climate change. Loosely, climate is average weather, and thus short-term climate prediction is a walk in the park compared with weather prediction. It is much easier to predict the average world temperature for next year, for example, than to predict the temperature at the bottom of your garden tomorrow morning. Even so, long-term climate predictions are far from easy, as we will see.

Why did it rain today when the forecast said sun? More generally, why is it so hard for meteorologists to predict detailed weather accurately when the likely weather is so trivial to predict? (The weather tomorrow will be the same as it is today works about 70% of the time on average, depending on latitude.) Here are a few more questions that you may have asked yourself whenever the state of the weather intrudes on your thoughts. Why do thunderstorms happen? Weather is seasonal for obvious reasons, so why is the weather on my birthday not always the same? What is a weather front? If weather is so variable, why doesnt the temperature ever go to 100 or +200? Why are there weather patterns, and will they be the same when my grandchildren grow up? Why can I see through rain but not fog?

Climate questions may intrude at a different levelthey are perhaps more important but less urgent. Why, like the atmosphere, is the global-warming debate increasingly heated? Is human industry responsible for this global warming, and, if so, can we reverse the process? How much of climate change is natural and inevitable, whatever we do?

I answer these questions and many others in the chapters to follow. The explanations will be accessible to an intelligent reader with no background in meteorology or climatology, though the underlying physics is immensely complex. Concerning meteorology, I concentrate mostly on the weather you get in your backyard, not so much on the extremes that occasionally wreak havoc around the world. One prosaic difference between weather and climate is politics, and politics does not mix well with rational debate or dispassionate analysis. So I will go to some effort to present you with the facts (Just the facts, maam, as Joe Friday would say) and eliminate the politics.

Except that this is impossible, when the subject is climate change. I adopt the view of most (almost all) scientists that the accumulated data point to a changing climate and to human activity as the likely cause. The problem is that, merely by accepting these data and making the inference, I am declaring a political viewpoint even though I infer via rational scientific arguments and not from any political preconceptions. So be it: I follow where science leads, and if I end up in a political camp, then, from my perspective, I got there accidentally. Please try to do the same; readers will get more out of this book if they consider it to be what the writer considers it to bean explanation of scientific phenomena, without any other agenda.

Here we attain the breadth of coverage while penetrating deeper into key aspects of our subject. Coverage cannot be comprehensive but will be deep enough to give insight.

NEW YORK

NEW YORK