For my fellow scientists.

Never stop seeking the truth.

Whats the forecast?

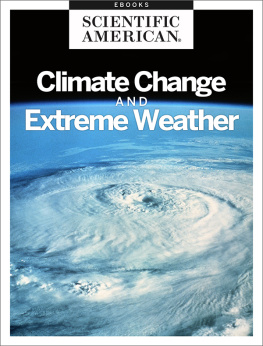

I heard this question a lot when I first started at The Weather Channel in 2003. People figured that if I worked at a 24-7 weather network, I must be a meteorologist. That was fine by me, Ive always been a closet weather geek, and besides, who doesnt secretly want to be a meteorologist? There is something so appealing about going to work every day and predicting the future without the use of tarot cards or constellations.

Im not sure how many people secretly want to be climatologists, but thats what I really am. And for anyone wondering what a climatologist is, heres a rough answer: Climatologists pick up where meteorologists leave off. We focus on weather timescales beyond the memory of the atmosphere, which is only about one week. And I guess you could say we also focus on timescales beyond human memory, which is shorter than you might think.

Climatologists look at patterns that range from months to hundreds, thousands, and even millions of years. The single most important and most obvious example of climate is the seasonal cycle, otherwise known as the four seasons. The seasons, a result of the 23.5 tilt of the Earths axis, affect the weather dramatically. And the physics behind the seasons are well nailed down. Summer, the result of one hemispheres being tilted closer to the sun, is warmer. And winter, the result of the other hemispheres being tilted away from the sun, is colder. The forecast for the seasons follows the physics; this is why, if I issue a forecast in January that says it will be significantly warmer in six months, you probably wont think Im a genius, but youll believe me.

There are countless other patterns on our planet that influence the weather. Take El Nio, for example. Nicknamed by fishermen along the coast of Peru after the Christ child, El Nio is a warm ocean current that typically appears every few years around Christmastime and lasts for several months. From its home in the tropical Pacific Ocean, El Nio is powerful enough to influence weather across the entire world. Unlike the seasons, which are controlled by astronomical forces, El Nio results from processes that happen here on Earth and that dont come and go like celestial clockwork. Climatologists have come to understand that the physics of El Nio result from a series of complex interactions between the ocean and the atmosphere. Technically, El Nio (EN) describes the ocean component, whereas the atmospheric component is known as the Southern Oscillation (SO). Thats why climatologists generally refer to it as ENSO.

During an ENSO event, the easterly trade winds weaken and the surface water off the coast of Peru and Ecuador warms up several degrees. This warmer water leads to increased evaporation, causing the air above it to rise and thereby affecting the winds. This conversation between ocean and atmosphere is nuanced and far-reaching. The atmosphere feels the influence of the warm ocean surface below it and conveys the message by shifts in tropical rainfall, which in turn affect wind patterns over much of the globe. For example, most El Nio winters are milder over western Canada and parts of the northern United States, and wetter over the southern United States from Texas to Florida. In other parts of the world, ENSO can bring drought to northern Australia, Indonesia, the Philippines, southeastern Africa, and northern Brazil. Heavier rainfall is often seen in coastal Ecuador, northwestern Peru, southern Brazil, central Argentina, and equatorial eastern Africa.

El Nio is just one of the ways climate can work itself into the weather. You might say meteorologists are obsessed with the atmosphere, whereas climatologists are obsessed with everything that influences the atmosphere. But in the end, were all obsessed with this notion of predicting the future. The atmosphere may be where the weather lives, but it speaks to the ocean, the land, and sea ice on a regular basis. Consider them influential friends that are capable of forcing the atmosphere to behave in ways that are sometimes, as in the case of ENSO, predictable. The hope is that if scientists can untangle all the messy relationships at work within our climate system, we should be better able to keep people out of harms way. The farther we can extend human memory, the longer out in time a society can see, and the better prepared well be for whats in the pipeline.

And that is where global warming enters the picture. If the four seasons are Mother Natures most prominent signature within the climate system, then you might say that global warming , the term that refers to Earths increasing temperature due to a buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, is humanitys most prominent signature. The big difference between global warming and other climate and weather phenomena is that in this case, were the ones doing the talking. And greenhouse gases are the chatter we use to influence the behavior of the atmosphere.

Decades of study suggest that this conversation will slowly drown out all others, its influence cutting across all timescales and all regions of the planet. Global warming has already begun pushing around the timing of the four seasons, and ongoing research shows that it is also influencing the weather. Meanwhile, climate scientists have developed a robust understanding of the physics of this human interaction with the atmosphere. They have collected data and built predictive models of the climate system that are capable of looking into the past andmore importantthe future. The forecast for Earth is in, and its not good.

Part I of this book explains the cutting-edge science behind this long-term climate forecasting, demonstrating why the predictive models for next century should be trusted in the same way that you trust the forecast for tomorrow on your local news. Here well examine the relationship between our weather today and our forecasts down the road, looking at how climatologists assess the changing statistics of extreme weather events and how these changing statistics play into the long-term forecast.

Well also look at the history of weather prediction and how it serves as the foundation of climate forecasts today. Weather forecasts and climate forecasts are based on the same principles of mathematics and physics. Yet they have inherent differences that allow weather forecasts to focus on short-term changes in the atmosphere, whereas climate forecasts focus on long-term changes to the entire system of ocean, land, and ice. Keep in mind: just as my initial forecast that July would be hotter than January didnt involve the weather on a specific day, so too a climate forecast for 2050 or 2100 looks at the big picture and not a specific day. A forecast for the year 2050 has the potential to be as meaningful and as useful as tomorrows weather forecast; its just used in a differ- ent way.

All this is important because if you dont trust the models, you wont believe the forecastsand the forecasts are what Part II of this book is all about. In Part II, well look at the forty-year forecasts for a few important places around the world. To start, I asked climate scientists to list the places they thought were most vulnerable to the threat of global warming.

I then narrowed the list down to seven key examples. (Ive included a fuller list of hot spots identified by climate scientists in Appendix 3.) I chose these seven places not necessarily because theyre the most endangered places or because the stories they offer are the most dramatic, but instead because collectively they demonstrate a spectrum of risks that exist with climate change. By mid-century, not every part of the world will be affected by global warming in the same way. Each location Ive chosen has its own Achilles heel, a vulnerability that unabated climate change will expose and exploit until the place is forever altered. Taken together these vulnerabilities show the breadth of repercussions that climate change will bring. It is my hope that whether taken as individual stories or as a whole, the predictions found in this book will demonstrate that global warming will hit all of us in the places we love and the homes where we live.