Denny - How the ocean works: an introduction to oceanography

Here you can read online Denny - How the ocean works: an introduction to oceanography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Princeton;NJ, year: 2008, publisher: Princeton University Press, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

How the ocean works: an introduction to oceanography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How the ocean works: an introduction to oceanography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Denny: author's other books

Who wrote How the ocean works: an introduction to oceanography? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

How the ocean works: an introduction to oceanography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How the ocean works: an introduction to oceanography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CHAPTER

Discovering the Oceans

T hroughout history, men and women have been drawn to the sea. In ancient times, people felt the same desire you and I feel today, the urge to stand and gaze upon the ocean. Then, as now, the ocean meant different things to different people. For the hungry, the sea was a source of abundant food: fish and lobsters, seals and seaweeds, whales and shrimp. For the audacious, the ocean was a route to faraway lands, an avenue of commerce and conquest. For the bereaved, the ocean epitomized grief: the oblivion into which their loved ones sailed, never to return, or the source of waves that consumed their villages. For the lucky, the sea was a source of pleasure and recreation.

These historical perspectives persist, but if you go down to the shore today and stare out to sea, your perspective is likely tempered by a modern point of view. With our recently acquired ability to travel into space, we now see the earth and its oceans as a whole (). Using satellite cameras we can locate storms and guide ships out of harm's way. We can count the phytoplankton that fuel the fisheries and direct fishermen to fertile grounds. Our sensors detect climatic anomalies as they begin, allowing us to predict their consequences. These are exciting times for humankind's interactions with the sea.

But this new perspective has two dangers. First, our capacity to see the entire earth can foster a sense of arrogance. It is easy to forget that the ability to observe is only the first step toward the ability to understand and control. As we learn how the ocean works, we must be careful to note the limits of our knowledge. Second, the grand view from space has the tendency to diminish our sense of personal contact. Awe-inspiring as it is, cannot convey the infinite expanse of the ocean at night when viewed from the deck of a small ship, the tang of salt on an ocean breeze, the crash of a breaking wave, or the shiver of water against your skin. To arrive eventually at a full appreciation of earth's seas, we first need to anchor our perspective in human experience. To that end, we retrace the steps of our ancestors and explore the arduous path by which human society discovered the oceans. In this chapter, we have time only for an outline of the full journeya mad dash through history. So, brace yourself as we begin with legends.

Figure 1.1. Earth from space. A photograph of the western hemisphere from the Visible Earth project at NASA (visibleearth.nasa.gov/view_detail.php?id=2429).

Ancient Myths

In many cultures, myths of the sea tell mostly of destruction. From the islands of the Pacific to the coasts of Central America, India, and the Middle East, when the ancient gods were displeased with men or women, they often chose the ocean rather than fire or wind as the instrument of their wrath. In the Bible, for instance, forty days and forty nights of rain caused the sea to rise and wipe the earth clean, sparing only Noah and those on his ark. Similar legends of earth-cleansing floods are common among civilizations in the Middle East. The Babylonians, for example, had a flood myth similar to that of the Bible, with a man named Utnapishtim playing the role of Noah. Likewise, the Sumerians had King Ziusudra.

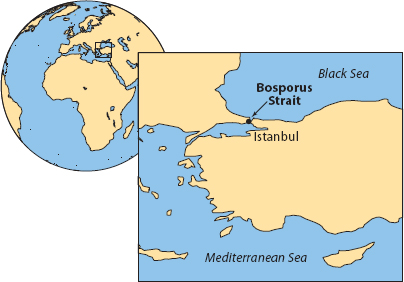

Figure 1.2. The Bosporus Strait, in what is now Turkey, separates the Black Sea from the Mediterranean Sea. Before the strait opened, the Black Sea was a freshwater lake.

Given this ubiquitous mythical reference to floods, some historians have suggested that there are historical bases for these tales. For example, legends of a great flood among coastal Indians of the Pacific Northwest may refer to tsunamis (tidal waves) caused by earthquakes, and the flood myths of Pacific islanders may describe waves resulting from volcanic eruptions.

A potential, although controversial, source of the Middle Eastern flood legends concerns the Black Sea. Today, the Black Sea is connected to the Mediterranean Sea by the Bosporus Strait, a narrow passage adjacent to Istanbul (). However, about ten thousand years ago at the end of the last Ice Age, a sill (essentially an earthen dam) closed the Bosporus, and the Black Sea was a freshwater lake. As the glaciers receded and earth's climate warmed, the level of the Black Sea dropped due to evaporation, while the level of the Mediterranean rose as the world's oceans absorbed the water from melting ice. Eventually, the Mediterranean broke through the sill separating it from the Black Sea, and the consequent flooding would have been catastrophic to the villages along the Black Sea's coastan event worthy of a legend.

Regardless of their precise origin, the flood myths convey the mystery and fear that tinged ancient encounters with the sea.

Commerce and Expansion

For all its destructive potential, the ocean has always tempted humans to risk its dangers in search of food and rapid transport. Boats built of wood and reeds traveled the waters of the Nile River in Egypt as long ago as 4000 BC, and many ancient civilizations of the Middle East used boats for fishing and coastal commerce. In particular, the Phoenicians were adventuresome merchants and adept sailors. In the first and second millennium BC, they developed a complex web of trade routes around the Mediterranean, and sailed as far north as the British Isles, trading for tin to use in making bronze. Similarly, in the Far East, coastal commerce using sampans and junks flourished in China. In the Arctic, the Inuit developed sea-going kayaks and umiaks, capable vessels from which they could hunt walrus and whales. The indigenous people of Chile, Peru, and Ecuador used small reed boats and large rafts for fishing and commerce.

In fact, some anthropologists suggest that the expansion of humans into North and South America occurred most rapidly not by land, but rather by sea. Experts agree that humans spread from Asia into North America after the last Ice Age, and have long assumed that humans spread throughout North America before subsequently expanding to Central and South America. It has recently been proposed, however, that the leading edge of this expansion was not through the middle of the continent, but rather along its western shore as groups used small boats to travel south. For example, a village at Monte Verde on the coast of Chile probably dates back to at least 15,000 BC, a time when humans were only beginning to populate central North America. Clearly, from very early times, our fear of the ocean has competed withand often lost toour urge to go exploring in boats.

Perhaps the best example of this wanderlust is the spread of humanity to islands in the Pacific. Starting in the Philippines about five thousand years ago, modern humans rapidly expanded their range in the open expanse of the Pacific Ocean. By 1600 BC they had reached New Guinea and the nearby Bismarck Archipelago. Forced onward by population growth, Polynesians next sailed to Samoa around 1200 BC, and by 500 AD, they had traveled all the way to Hawai'i and Easter Island ().

It is clear that this expansion was not the accidental result of a few fisher folk being blown offshore and ending up on other islands. Hawai'i, for example, was settled by sailors traveling from the Marquesas across 3700 kilometers (2300 miles) of open ocean. That monumental leap required ocean-going outrigger canoes large enough to carry not only people but also the plants and animals of their culture. And finding Hawai'i required exceptional working knowledge of navigation and the sea. Each step in the Polynesian expansion involved skill, planning, and a group effort.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «How the ocean works: an introduction to oceanography»

Look at similar books to How the ocean works: an introduction to oceanography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How the ocean works: an introduction to oceanography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.