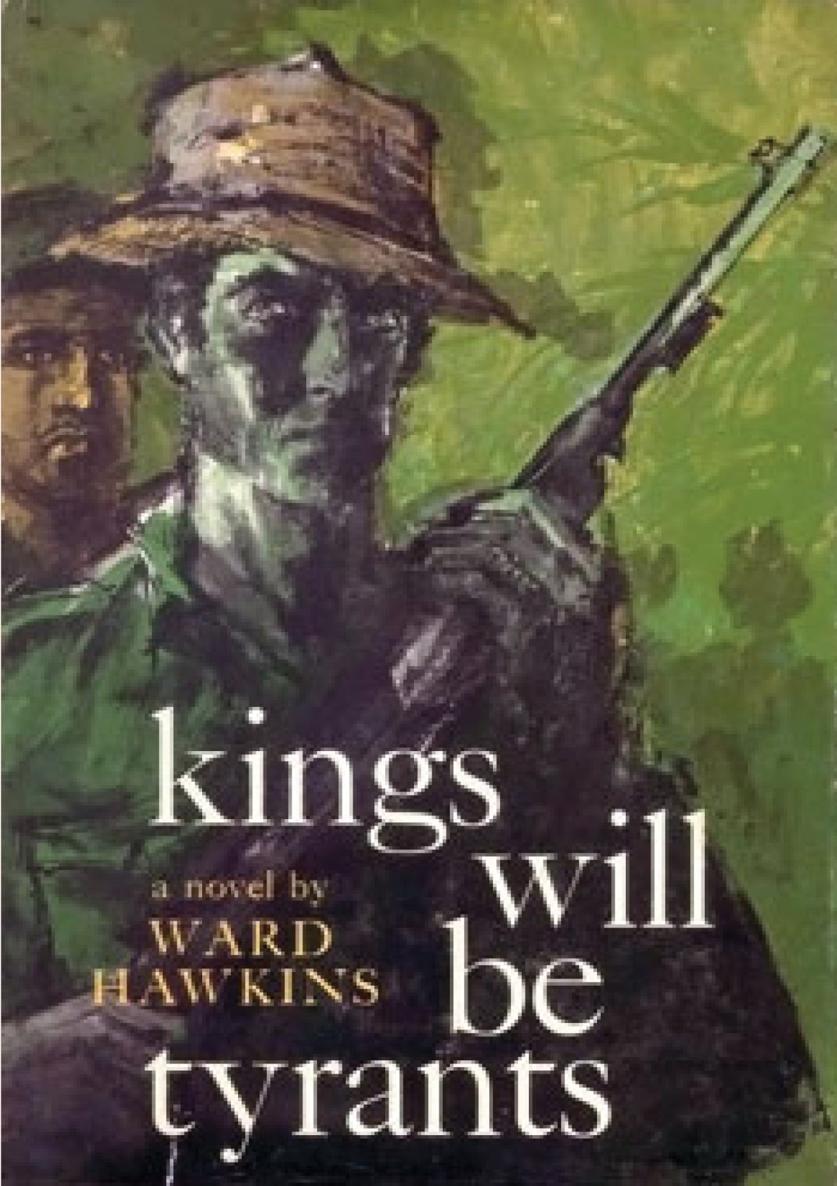

1

THE DAY HAD just begun. There were still a few places of near darkness in the hollows and beneath the deep undergrowth, but the goldness of the sun was only moments away. The birds were speaking of it noisily. The sky was becoming very blue and the frayed veil of high clouds was turning white.

Presently, of course, it would be hot. But now it was pleasantly cool and moist. A man would do well, OBrien thought, to do all his living at sunrise. There was sweating at noon, there was fear at night, but in the morning there was hope. A man had to work very hard to despair, and to be afraid, at sunrise. At sunrise, all his chances were new.

The dampness of the ground was making OBriens back itch, but he did not move. He had awakened thus and had not moved anything except his hands since the moment of awakening. He had used his hands to make sure about the carbine at his side and the automatic at his hip. But the movement had been small, and it was possible the small boy, who was watching him, had not noticed it.

The boys name was Carlos Daz, and he was ten. OBrien had heard him come as softly as a mouse and knew that he was squatting on his heels close by, waiting patiently. He could see the boys face against his closed eye lids, the face of a small, deeply tanned angel, with curly dark hair and long-lashed dark eyes. He could also see the clothes, torn and buttonless, and the bare feet. The lack of shoes did not trouble Carlos Daz, nor was it an inconvenience. The calluses and the dirt on the boys feet were protection enough.

OBrien was thirty-one. He was long and lean and very strong, with a face burned dark by the sun and hair burned to the color of straw. His nose was formidable, something like a cliff, and while it was true he would have looked better with less nose, he was not ugly. He had gray eyes that could be warm and a mouth that smiled well. To Carlos Daz, who cared nothing about noses, OBrien was beautiful next to Christ.

You do not fool me, the boy said in his native tongue, which was Spanish. You have been awake while I counted to one hundred.

You cannot count that far, OBrien said in the same tongue. Not without cheating.

I cheated only a little.

You should not cheat at all, OBrien said. In any case, I am awake. How can a man sleep with a small boy staring at him...a small boy with a dirty face?

You do not know about my face, Carlos said. You have not opened your eyes.

I know about small boys.

You do not like small boys, Carlos said slowly.

Have I said so?

You have shown it.

After a moments thought, OBrien said, Then that must be the way I feel. If you have pride, you will not force yourself where you are not wanted. Be a boy of pride now. Go away.

Carlos Daz went away.

OBrien sat erect.

He was wearing a faded suntan uniform that had once belonged to an officer in the army of Fulgencio Batista. The uniform had been cleaned and repaired, though it was dirty now, and the shoulder patch of the July 26 movement had been sewn on. The uniform was small for OBrien, but it served to indicate he was an officer. His shoes were worn American paratrooper boots, his helmet was a soiled panama hat.

He had slept a matter of twenty minutes, but in that time, he saw now, nothing had changed in the small clearing. The eight men who were here were talking quietly, smoking, cleaning weapons and dozing. The commander of the group, Toms Vilar, was sitting on a flat stone, picking his teeth. The task was not small where Toms Vilar was concerned. He had been born in a very poor family, who had known nothing of dentists, and as a consequence had very bad teeth.

OBrien had been surprised to find the notorious Toms Vilar was so young. He was no more than twenty-six. A short, round man, he appeared soft. But he was not soft; he could move with agility and to follow him for a day was to know complete exhaustion. Toms Vilar liked food, drink, women, being alive, being a revolutionary, and being in command, and he did not place one of these things before another. In. addition, he liked killing, and OBrien could not say how much of that would satisfy him. More, certainly, than could be justified.

Carlos mother, Angela Daz, was kneeling at a small fire. She spoke to OBrien, using Spanish as they all did, since OBrien spoke the language as well as any of them, and they spoke English badly if at all. I have made coffee.

Is it good? OBrien asked, teasing.

I promise only that it is hot.

In a moment, then, OBrien said, smiling.

Angela Daz had come to OBriens blanket on the third night he had known hera matter of seven days agowithout being asked, and the curious thing about this was that in her heart Angela was a virtuous woman. She had come to him out of necessity. A young woman, among men trained to violence, with a son to remind them constantly of her ability to mate, was a source of trouble that could lead to killing until she became the woman of one man in particular. Because of this need, she had chosen OBrien.

But not for this need alone. She had seen in his eyes and in his face the calm understanding that would allow him to accept her without undue concern and certainly without remorse. And she had seen in his lean and powerful body the virility her body required. That her body required more than seemed reasonable and decent was both her pride and her shame.

She was twenty-five, a woman with firm, full breasts and fruitful hips. She wore a mans trousers and a mans shirt, and her black hair was cut off, raggedly, for convenience. But she was not bad to look at. She had regular features, a good nose and mouth, long dark lashes and large dark eyes. OBrien understood that she had seen Carloss father die of a cut throat, but he had not been able to find insanity in her eyes, or even dullness.

He said, The Daz family is a family of dirty faces.

She shrugged. When I cook in the Palace, I will wash ten times a day.

Toms Vilar made a snort of laughter. What do you say to that, OBrienis this a woman? Give me a hundred men with as much purpose and I would hang Batista within a week.