This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1960 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

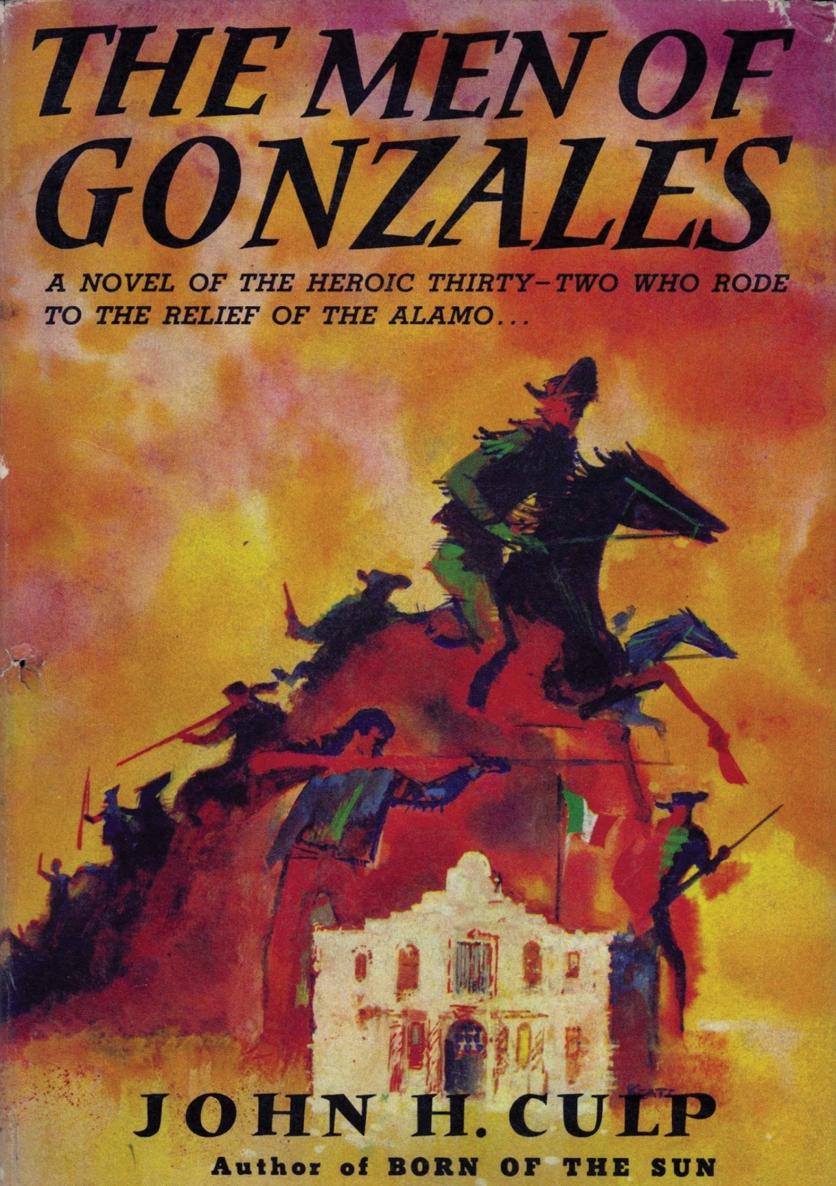

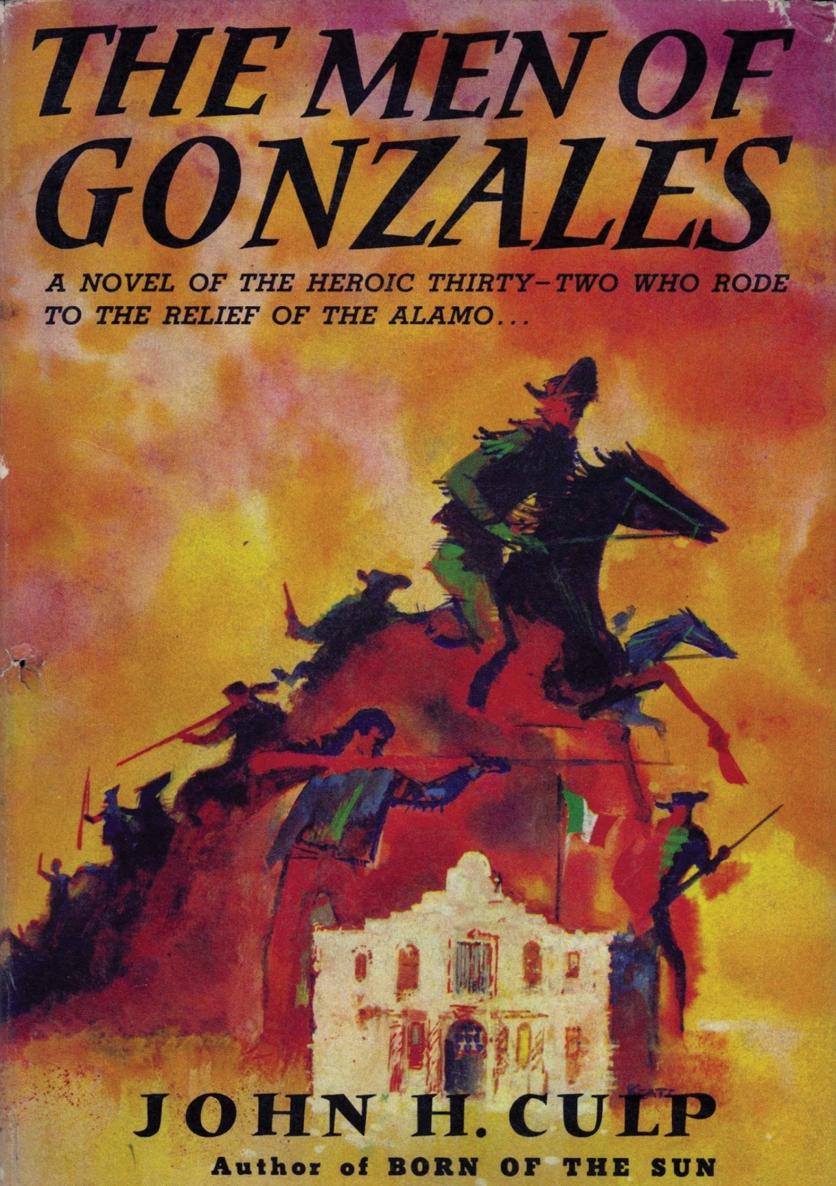

THE MEN OF GONZALES

BY

JOHN H. CULP

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DEDICATION

To

the memory of my father

whose courage and beliefs

were uniquely his own.

AUTHORS NOTE

On March 1, 1836, thirty-two determined men from Gonzales, guided by John W. Smith, reached Salado Creek, on the outskirts of San Antonio, to come to the relief of the Alamo. This work of fiction is their story.

Of all the men of Texas, they alone had heeded the call of Travis, the commandant. Knowing that certain death awaited them, they still rode forth to their duty.

In the story, the names of the men are fictitious, except for that of Albert Martin, who serves as a symbol of the rest. The distance of time has to a large extent obliterated personal incident; hence, it is invented for Martin and for other characters. Similarly, no attempt has been made to put in proper sequence or person the departure of the various couriers from the besieged fort; in the story, for instance, Jared Abrams carries the message from Travis which actually Albert Martin carried, and Albert Martins arrival in Gonzales is saved for several days later. In some cases, the events pictured as occurring in the settlement of Gonzales are factual, or based on factor what, in the light of previous events, would be reasonable to suppose; other events are fictional. There was probably no oak tree stump for Cristobal, and the little brass cannon, which earlier had fired the first shot against Mexico in the Texas War of Independence, has been retained in the plaza although it had perhaps disappeared by this time, and there are similar instances of invention, or a slight shifting of historical event in time, to further the story. It has seemed paramount to catch the spirit of the town and people, rather than present factually what history has recorded, even when historical fact can accurately be separated from the veil of legend which shrouds the last days of the Alamo.

The ages of some of the men are in keeping with tradition, and not fact, and Grampappys age is his own. No boy played Juans part on Salado Creek, but any boy should like to have.

What happened to the little cannon? Lenore Bright, curator of the Gonzales Historical Museum, writes: We would like to know what became of it. Some claim it was in the siege of Bejar, others that it was abandoned on the Cibolo, on the way to the siege, because of sparks from friction that almost started a fire. Still other sources say it was dumped in the Guadalupe.

But whatever its fateif it was abandoned on the Cibolo, as many claimits mouth still speaks in time and in the minds of men with the same voice of freedom which animates the men of this story.

Grateful appreciation is expressed to Miss Bright for her correspondence regarding certain research and material, and her courtesy in Gonzales by making the facilities of the museum available, and most of all for her unselfish willingness to be of assistance, which, after all, is but a modern manifestation of the spirit of Old Gonzales.

If you visit the town and want an oak tree stump to view the river from, the good people will probably pro-vide one.

John H. Culp

Shawnee, Oklahoma

August 31, 1959

1

Qu nombre! What a name! And all that afternoon I had chased my mothers old yellow cow, Pablita Hurfana, through the fields and trees along the winding San Antonio River. At last, as I neared the eastern hills of the Salado, I came upon the six men who had hidden in the bare-branched post oak grove, and for the second day the cannon of the Mexican armies bombarded the Alamo.

Before the fire a tall man in a coonskin cap and buckskins stood with his long rifle, and near him on the ground lay the five other men.

Then, wholl go with Kirbit into the Alamo? the tall man was saying, and now the other men heard me and leaped to their feet, holding their rifles raised. They all shoved close, and I was frightened. The tall man, Kirbit, clapped his hand upon my shoulder, and I was so lost among all the long rifles I trembled.

That day it was bad on the land. All over the smoky fields the hunted cattle died, and the jacales and faraway cabins burned. The odor of death rose in the air above the thorny mesquite and chaparral, and the Mexican soldiers dug their trenches beyond the Alamo and more armies came from the Rio Grande. Yesterday, their General Santa Anna had placed his cannon across the river to begin the bombardment, and beyond them his blood-red flag flew from the open bell tower of the Cathedral of San Fernando, in the flat-roofed town of Bejaror as some called it, San Antonio de Bejar.

Apart from Bejar, on this side of the river, stood the gray stone walls of the fort where our Texians were besieged, the ruins of the roofless old mission chapel, with the stone statue of St. Anthony niched beside the door, rising above the lower walls of the barracks. From the chapel and the barracks walls our men fired at the Mexicans with their rifles, and now and then from the ramps and scaffolds with their booming cannon. Oh, it was bad! The siege of the Alamo had only started, and today the Mexican soldiers had driven my mothers cow, Pablita Hurfana, away from our cabin.

Go watch the prairie, Kirbit told two of the men in buckskin. Who are ye? he asked fiercely, grasping my shoulder so hard it hurt. Did ye guide soldiers here?

No, seor! No! I am a Texian! I do not like the soldiers. They have wounded my father and driven away my mothers cow. They have stolen our geese and chickens, and our fields are burning. I do not like the soldiers, seor!

Do ye tell the truth? Kirbit scowled, shifting the curved powder horn which hung from his shoulder.

S, seor. It is all true.

Do not call me seor, Kirbit said. After today yell use no Mexican word with me.

I talk two ways, seor. Look! I held up a finger. My father is whiteall whitelike you. I held up two fingers. My mother is part white, part golden. Three fingers. I do not understand such things, seor, but I am all golden.

A toothless old man who had left us to squat by the fire pursed his puckered lips and cackled like my mothers hens in their yard.

Kirbit frowned. Quiet, Grampappy. Ill have the truth of this.