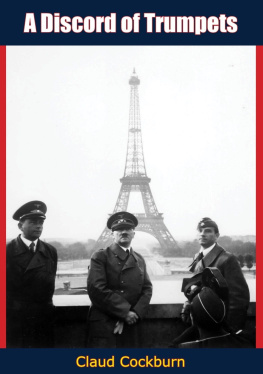

BEAT THE DEVIL

Claud Cockburn

New Introduction by Alexander Cockburn

First published in Great Britain by T. V. Boardman 1953

Introduction copyright Alexander Cockburn 1985

THE AUTHOR

Francis Claud Cockburn was born in 1904 in Peking, where his father was a consular official, and came to Britain at the age of six months, along with a Chinese nurse. He was afterwards educated at Berkhamsted and at Oxford, where he was one of the 'Brideshead' generation. A travelling fellowship then took him to France, Hungary and Germany. In 1929 he joined The Times as a foreign correspondent, working from Berlin, Paris, New York and Washington, but his increasingly left-wing views led him to resign in 1932. The following year he joined the Communist Party and founded his immensely influential paper The Week, which was denounced by Goebbels as 'the source of all anti-Nazi lies'. In 1935, as 'Frank Pitcairn', he began writing for the Daily Worker and was their reporter from the Spanish Civil War, in which he fought.

After World War II, Cockburn left the Worker, gave up The Week and, in 1947, left the Party. But he never abandoned his Marxist principles or his life-long commitment to journalism - he continued to write from his home in Ireland, where he had settled with his wife Patricia and their three sons, Alexander, Andrew and Patrick, now also journalists. (With his second wife, Jean Ross, the model for Isherwood's Sally Bowles, he had had a daughter, Sarah.) He became a regular contributor to Punch, the New Statesman and, later, to Private Eye and the Irish Times', he wrote short stories and, between 1951 and '74, five novels (Beat the Devil, Overdraft on Glory and The Horses under the pseudonym of James Helvick, and Ballantyne's Folly and Jericho Road - all being published in Hogarth), as well as several books of non-fiction, including the famous autobiographical collection, I, Claud (1967). He died in Cork in December 1981.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

My father wrote Beat the Devil in 1949, some of it in the house we had just acquired three miles outside Youghal, County Cork, and some in a summer cottage taken for August in the tiny village of Ardmore, which was all of eight miles away, across the Blackwater in County Waterford. These were the years immediately after his departure from London and from the Communist Party in 1947 and the name Cockburn did not have benign associations for the publishers and magazine editors crucial to our well-being. Since my father had left the Party without fanfare it took a while for his absence to register; then finally the security forces, in the form of the Special Branch and the Daily Express, sent men to investigate. In the absence of nutritious commentary from either my father or the locals the investigators concentrated on my father's locomotive resources. The man from the Special Branch established by zealous questioning - all subsequently related to us - that boat, train and car had been the various means assisting my father's translation from London to Youghal, while all the Express man could report was that the ex-Red was now using a bicycle to get about, 'head down against the wind and,' he asked dramatically, 'against the Party line?'

Neither my father nor my mother could drive and, for that matter, we wouldn't have been able to afford a car. But Ireland, or at least our particular part of it, was still essentially a nineteenth-century rural society and the cost of living was negligible by present-day standards; and anyway the pretensions of genteel poverty have never been part of the Anglo-Irish sensibility. You could be flat broke with rain pouring through the roof and bailiffs pouring down the drive and still hold head high - in our case, above the handlebars of the famous bicycle or in the horse and trap which was our alternative means of transportation. This was just as well because we were indeed flat broke, even though my father, banging away on his elderly Underwood, had developed a whole family of pseudonyms to try to confine the wolf at least to the hallway of our spacious and draughty Georgian house.

My father later wrote in his memoirs that a guest had described in the visitors' book what he called the 'literary colony' at Youghal:

He claimed to have met Frank Pitcairn, ex-correspondent of the Daily Worker - a grouchy, disillusioned type secretly itching to dash out and describe a barricade. There was Claud Cockburn, founder and editor of The Week, talkative, boastful of past achievements, and apt, at the drop of a hat, to tell, at length, the inside story of some forgotten diplomatic crisis of the 1930s. Patrick Cork would look in - a brash little number, and something of a professional Irishman, seeking, no doubt, to live up to his name. James Helvick lived in and on the establishment, claiming that he needed quiet with plenty of good food and drink to enable him to finish a play and a novel which soon would bring enough money to repay all costs. In the background, despised by the others as a mere commercial hack, Kenneth Drew hammered away at the articles which supplied the necessities of the colony's life.

'James Helvick', the name under which Beat the Devil was originally published, had been my mother's suggestion. Across the bay from Ardmore the long green finger of Helvick Head poked out into the sea and in the end its borrowed name decorated my father's first three novels - Beat the Devil, Overdraft on Glory and The Horses. These were all written in the 1950s. When my father returned to fiction with Ballantyne's Folly in 1970 and Jericho Road in 1974, they were launched under the true colours of his own name.

Beat the Devil was published at the beginning of the Fifties, in England by Boardman and in the US by Lippincott. Both are now defunct, at least as houses publishing trade books. The advance against royalties provided by Boardman was, to my mother's recollection, somewhere between 200 and 300, and the sum for American rights was $750. This sort of money, though not as paltry as it now appears, did not long stay the bailiffs and things were looking bad as we went off to stay, for the Dublin Horse Show week, with Oonagh Oranmore at Luggala, her house in the Wicklow mountains.

Quite apart from the simple comfort of not having water on the floor and bailiffs at the gate, Luggala was a wonderful place to go in the early and mid-1950s. Writers and artists from Dublin, London, Paris and New York drank and sang through the long hectic meals with a similarly dissolute throng of politicians and members-in-good-standing of the caf society of the time. And during this particular Horse Show week Luggala was further dignified by the presence of the film director John Huston and his wife of those years, Ricky. My father was a friend of Huston - from his stint in New York in the late 1920s perhaps, or maybe from Spanish Civil War days - and quite apart from the pleasures of reunion there was Beat the Devil, ready and waiting to be converted into a film by the famous director of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

My father spoke urgently to Huston of the virtues of Beat the Devil, but he found he had given, beneath fulsome dedications, his last two copies to our hostess and to a fellow guest, Terry Kilmartin. These copies were snatched back and thrown into Huston's departing taxi. A week later Huston was in Dublin again, shouting the novel's praises. He and Humphrey Bogart had just completed The African Queen and were awaiting the outcome of that enormous gamble. I can remember Huston calling Bogart in Hollywood and reading substantial portions of the novel to him down the phone - a deed which stayed with me for years as the acme of Babylonian extravagance.

Next page