This edition is published by Arcole Publishing www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books arcolepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1956 under the same title.

Arcole Publishing 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

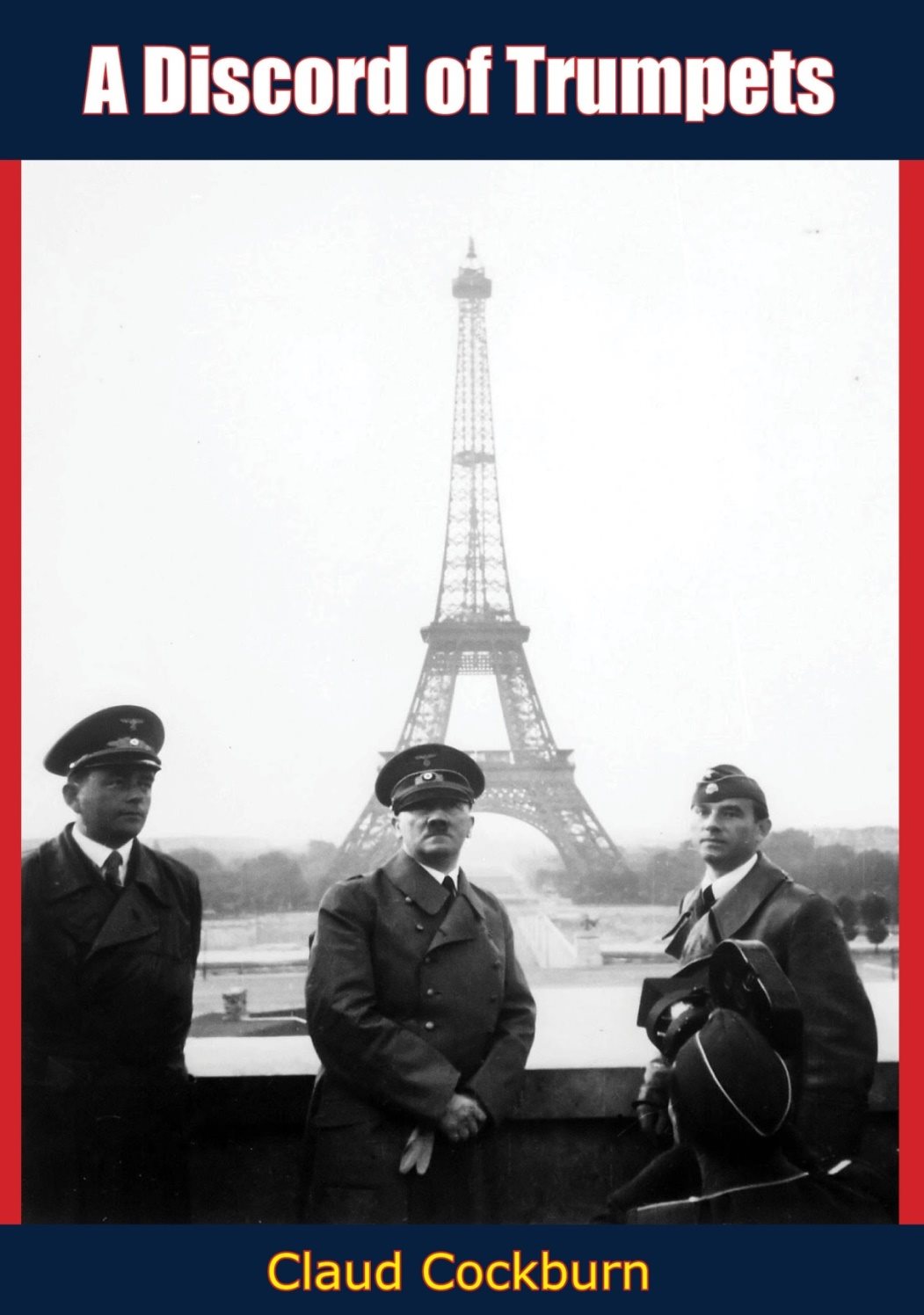

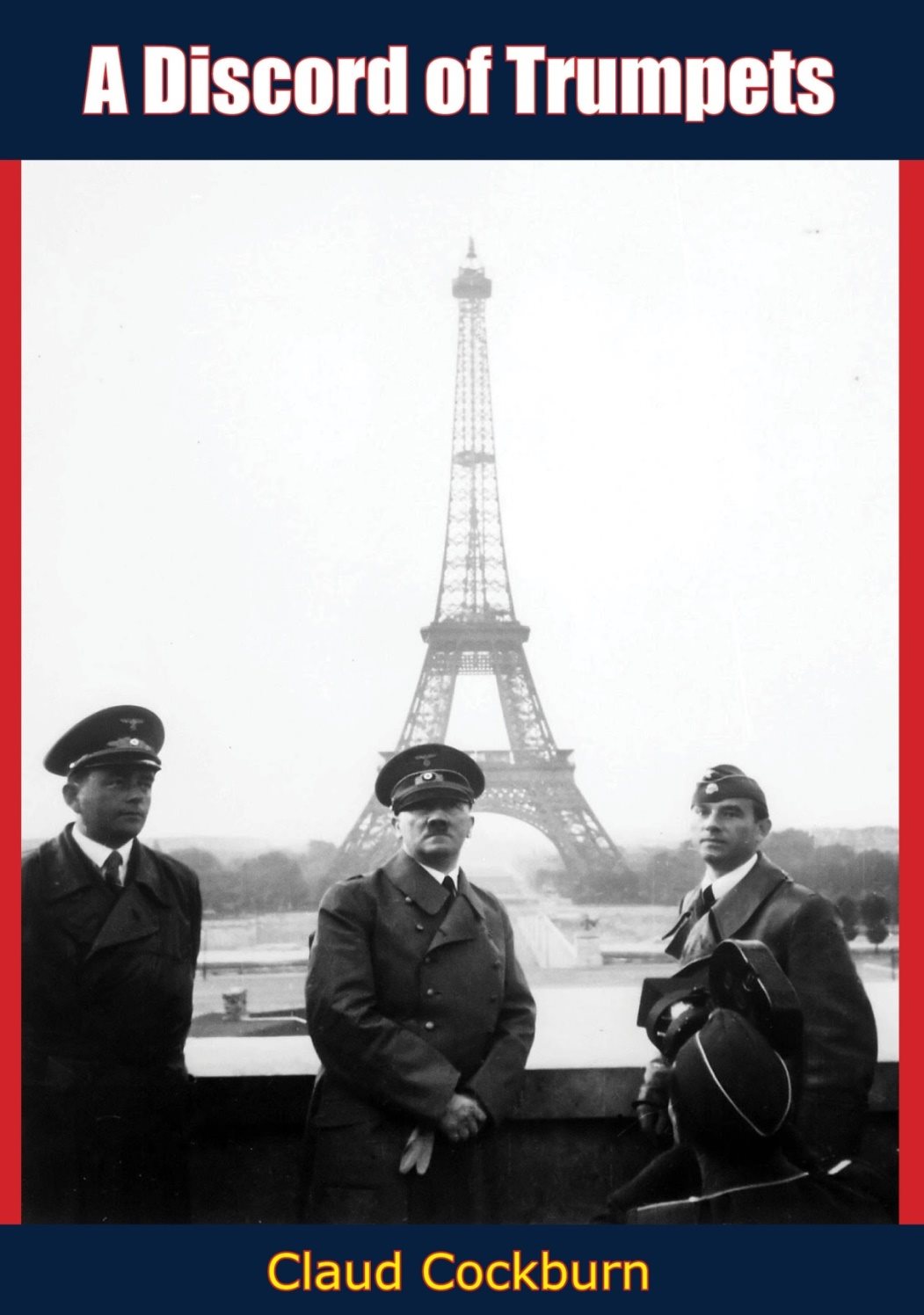

A DISCORD OF TRUMPETS

AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY

BY

CLAUD COCKBURN

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

1

IN our little house, the question was whether the war would break out first, or the revolution. This was around 1910.

That period before World War I has since got itself catalogued as a minor Golden Age. People living then are said to have had a sense of security, been unaware of impending catastrophe, unduly complacent.

In our neighborhood, they worried. They thought it was the Victorians who had had a sense of security and been unduly complacent.

There were war scares every year, all justified. There was the greatest surge of industrial unrest ever seen. There was a crime wave. The young were demoralized. In 1911, without any help from television or the cinema or the comics, some Yorkshire schoolboys, irked by discipline, set upon an unpopular teacher and murdered him.

Naturally, alongside those who viewed with alarm, there were those who thought things would probably work out all right. Prophets of doom and Pollyannas, Dr. Pangloss and Calamity Janeall lived near us in Hertfordshire in those years, and I well remember being taken to call on them all on fine afternoons in the open landau, for a treat.

At home the consensus was that the war would come before the revolution.

This, as can be seen from the newspaper files, was not the most general view.

At our house, however, people thought war was not any nicer than revolution, but more natural.

It was in 1910 that my father desired me to stop playing French and English with my tin solders and play Germans and English instead. That was a bother, for there was a character on a white horse who was Napoleonin fact, a double Napoleon, because he was dead Napoleon, who fought Waterloo, and also alive, getting ready to attack the Chiltern Hills where we lived. It was awkward changing him into an almost unheard-of Marshal von Moltke.

Guests came to lunch and talked about the coming German invasion. On Sundays, when my sister and I lunched in the dining room instead of the nursery, we heard about it. It spoiled afternoon walks on the hills with Nanny, who until then had kept us happy learning the names of the small wild flowers growing there. I thought Uhlans with lances and flat-topped helmets might come charging over the hill any afternoon now. It was frightening, and a harassing responsibility, since Nanny and my sister had no notion of the danger. It was impossible to explain to them fully about the Uhlans, and one had to keep a keen watch all the time. Nanny was no longer a security. (An earlier Nanny had herself been frightened on our walks. She was Chinese, from the Mongolian border, and she thought there were tigers in the Chilterns.)

One night at haymaking time when the farm carts trundled home late, I lay awake in the dusk and trembled. Evidently they had come, and their endless gun carriages were rolling up the lane. My sister said to go to sleep; it was all right because we had a British soldier staying in the house. This was Uncle Philip, a half-pay major of Hussars whose hands had been partially paralyzed as a result of some accident at polo.

His presence that night was a comfort. But his conversation was often alarming, particularly after he had been playing the War Game.

In the garden there was a big shed, or small barn, and inside the shed was the War Game. It was played on a table a good deal bigger, as I recall, than a billiard table, and was strategically scientific. So much so, indeed, that the game was used for instructional purposes at the Staff College. Each team of players had so many guns of different caliber, so many divisions of troops, so many battleships, cruisers and other instruments of war. You threw dice and operated your forces according to the value of the throw. Even so, the possible moves were regulated by rules of extreme realism.

The game sometimes took three whole days to complete, and it always overexcited Uncle Philip. The time he thought he had caught the Japanese admiral cheating he almost had a fitnot because the Japanese really was cheating, as it turned out, but because of the way he proved he was not cheating.

The admiral and some other Japanese officers on some sort of goodwill mission to Britain had come to lunch and afterward played the War Game. As I understand it, they captured from the British teammade up of my father, two uncles and a cousin on leave from the Indian Armya troopship. It was a Japanese cruiser which made the capture, and, at his next move, the admiral had this cruiser move the full number of squares which his throw of the dice would normally have allowed it. Uncle Philip accused him of stealthily breaking the rules. He should have deducted from the value of his throw the time it would have taken to transfer and accommodate the captured soldiers before sinking the troopship. He found the proper description of this cruiser in Janes Fighting Ships and demonstrated that it would have taken a long timeeven in calm weatherto get the prisoners settled aboard.

The admiral said, But we threw the prisoners overboard. He refused to retract his move.

Uncle Philip hurled the dice box through the window of the shed and came storming up to the house. Even in the nursery could be heard his curdling account of the massacre on the troopship.

Sea full of sharks, of course. Our men absolutely helpless. Pushed over the side at the point of the bayonet. Damned cruiser forging ahead through water thickening with blood as the sharks got them.

Even when the Japanese fought on the British side in World War I Uncle Philip warned us not to trust them.

His imagination was powerful and made holes in the walls of reality. He used to shout up at the nursery for someone to come and hold his walking stick upright at a certain point on the lawn while he paced off some distances. These were the measurements of the gun room of the shooting lodge he was going to build on the estate he was going to buy in Argyllshire when he had won 20,000 in the Calcutta Sweep. Sometimes he would come to the conclusion that he had made this gun room too smallbarely room to swing a cat. Angrily he would start pacing again and often find that this time the place was too large. I dont want a thing the size of a barn, do I? he would shout.

Once, some years earlier, his imagination functioned so powerfully that it pushed half the British fleet about. That was at Queen Victorias Diamond Jubilee in 1897, when the fleet was drawn up for review at Spithead in the greatest assembly of naval power anyone had ever seen. Uncle Philip and my father were invited by the admiral commanding one of the squadrons to lunch with him on his flagship. An attach of the admiral commanding-in-chief was also among those present.

Next page