For Logan and Willow

Contents

Acknowledgements

M y sincere thanks are due, for their invaluable help and advice, to Dr David Caldwell of the National Museums Scotland, Gerry Brooke and Mark Steeds of Bristols Long John Silver Trust, Scottish historian Mark Jardine and (no relation) Selkirk descendant Allan Jardine and his late mother, Ivy, whose unquenchable enthusiasm for her villages famous son surely deserves the most honourable of mentions.

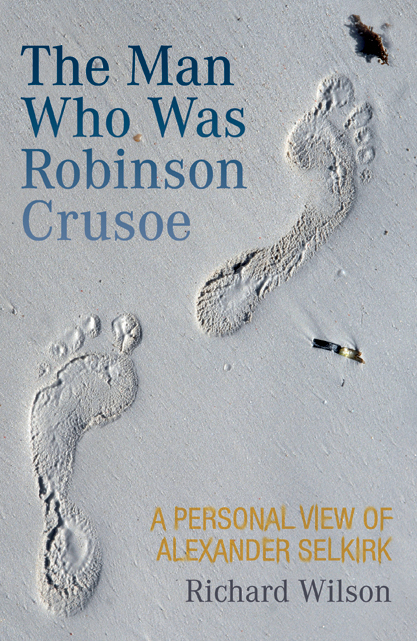

Introduction

ALEXANDER SELKIRK

Born 1676

Ran away to sea 1695, aged 19

Died 13 Dec, 1721 at the age of 45

T hree hundred years ago, a wild-eyed, fast-running creature looking and smelling more like an agitated animal than a human being was rescued from a deserted volcanic island by an English ship 418 miles off the coast of Chile. He had broken teeth, a skeletal body, a long beard and hair and his clothes were tattered goatskins. He had been marooned there for four years and four months.

So who was this castaway under his coat of many goatskins and behind his little white flag? As his rescuers soon established, he was a Scottish sailor from the Fife fishing village of Lower Largo who was about to become Daniel Defoes inspiration for one of the most popular stories ever published Robinson Crusoe. His name was Alexander Selkirk, or Selcraig (as he was born), or Selchraig, Selchraige, Selcraige, or Sillcrigge (as he variously appeared in kirk session minutes); or Silkirk (in his two wills); or Selchrig (in his common-law wifes plea to a minister).

But it is Selkirk that has come down through the centuries, and a popular theory is that he chose it from all the spelling variations to make his name more pronounceable to his mainly-English employers as he charged across the years and across the oceans and, in the process, made his most memorable stop-over on the island of Juan Fernandez.

As an east coast Scot myself, I have long been fascinated by character and story of the original Robinson Crusoe. Indeed, I once penned the words of his imaginary spirit to colour a previous book, a device also occasionally employed in this one, in the absence of his own diary. Here and there the reader will find passages of my imagined words for Selkirk. Where did they come from? I dont know, but I felt oddly gripped by that spirit, and the words flowed out in old language with such ease I found it difficult to return, when required, to modern language.

In the Eighties, as a magazine editor, I spent (perhaps too) much time hunting down the whereabouts of three potential Crusoe muskets; and the one which eventually materialised was brought home to the little museum which the vestigial elements of his family kept briefly in his home village.

I also remember, several years before that, plodding around the vast volumes of the people-packed Frankfurt Book Fair with a home-made dummy of a pictorial book on the mans life. While I raised more perspiration than publishers interest then, I have more recently noticed quite a bit of international material in the subject. So I feel the time has come to, once and for all, stake a modest claim born of such ongoing interest; to put my own full point on this tale around which I have been tiptoeing for decades; to tell my own Scottish version of the adventures of my famous countryman.

Or should that be infamous? For the unpalatable fact is that, despite his romantic aura, Alexander Selkirk appears not to have been a very nice person; he was more of a loutish adventurer, a hard-drinking and rough-talking buccaneer, and ... well, to be frank, it has been quite hard in my enquiries for this book to quote anyone, from any period since his death, with much of a kind word to say about him.

As a seventh son thought by his mother to have been thus born lucky, the mariner is described as spoiled and wayward in the 1829 biography by John Howell, who said he was made only worse by the indulgence of his mother, who concealed as much as she could his faults from his father. Sometimes his father couldnt miss these, however, as he often had to step in when the young Alexander had violent fights with his siblings and was brought before the disciplinarians of the Kirk to confess and repent his sins.

Even today, his reputation in Lower Largo suffers from a very negative folk memory. In the village pubs, he is universally said to have been a bad lad. And to be specific, local artist Martin Anderson calls him a rogue and a philanderer while Dorothy Shepherd, who lives in the house that replaced the sailors birth cottage, says he was a very bad-tempered man.

Perhaps the most positive comments about him were made by the journalist Sir Richard Steele who interviewed him about his solitary years on Jan Fernandez and wrote from his notes a famous article in The Englishman magazine in 1713. He is a man of good sense, said Steele, who found Selkirk to be quite communicative because he was familiar to men of curiosity. While he thought Selkirks aspects and gestures seemed as though he had been much separated from company, there was a strong, cheerful seriousness in his look and a certain disregard to the ordinary things about him as if he had been sunk in thought.

Steele said Selkirk felt his return to company was a mixed delight and quoted him as saying that, even though he was now worth 800 which was quite a fortune in those days he was never so happy as when he was not worth a farthing. Others seeking information from Selkirk found him less willing to talk about his time on the island. One said he found Selkirk an unsociable, odd kind of man.

What is clear is that Selkirk was no angel. Most books of this nature like to paint their central character as a hero. And much as I would like to think that way about the man whose experiences undoubtedly inspired Defoe to create his classic hero, I fear that what we have here is a bit of an anti-hero. Selkirks delinquent character does not sit comfortably with either that authors nice English middle-class Crusoe or with our own wished-for image of a swashbuckling 18th-century braveheart triumphing with good over evil. Swashbuckling might have been a part of his life, but it is the good part with which we have some trouble in painting Selkirk as a man to be admired.

He did have, nonetheless, many admirable qualities: Having been well educated in his village school, he was an excellent navigator on whose abilities world-ranging captains and their officers (with the exception of one) were happy to depend. He was a man who could improvise to survive, as his marooning on that remote island proved. He could, in the right mood, be quite commonsensical. He was also undoubtedly brave, albeit in a foolhardy way. And as we know from his attempts to recreate elements of his much-missed island back in Scotland, he could be quite sentimental, which suggests some sensitivity: He frequently bewailed his return to the world, which could not, as he said, with all its enjoyments, restore to him the tranquillity of his solitude.

But it cant be denied that he was also selfish, egotistical, self-opinionated and ever-ready to pick a fight. A perverse blessing in disguise? After all, had he not been so headstrong he would not have fetched up on Juan Fernandez in 1704 to make it his home until 2 February, 1709, and thus inspire the Crusoe tale. On arrival there it was his stubborn conviction that their ship was unable to go much further without thorough repairs which caused the final break-up with his captain. When he refused to go further if his advice was not taken, the Scots bluff was called by the captain abandoning him in disgust.