Chapter I

MAROON

H e stands alone on the shoreline. He is such a savage sight that the six oarsmen in the approaching ships boat take quick glances over their shoulders as they row closer. His legs and callused feet are bare, and the hairy pelts of animals cover his upper thighs and body. He has stitched the skins together into an uncouth jacket, using rawhide thongs. A clumsy, rough cap of the same material protects his head. The coarse animal hair on the pelts merges with the overflow of his long beard and his wild mat of hair so that he resembles a shaggy animal, excited and reared up on two legs.

The two officers in the boat, Captain Thomas Dover and Second Mate Robert Frye, scan the stony beach, trying to judge the best place to land, and the hairy creature waves to them urgently, pointing to a suitable spot. He then rushes forward to greet them as they splash ashore. The visitors are too astonished to speak as the apparition, choking with emotion, throws his arms around the new arrivals and hugs them. The hirsute man has not been able to tan the skins he wears. They reek as when they clothed their original owners, the wild goats of the island. The man stinks.

The Dukes yawl finds him. Three weeks earlier Captain Woodes Rogers had steered his thirty-gun private ship of war around Cape Horn after a difficult four-month passage from Cork in Ireland, and slipped furtively into the Pacific. He and Captain Stephen Courtney of the accompanying twenty-six-gun Duchess then lay course for an uninhabited island nearly 400 miles off the coast of Chile. This is poachers thinking. The remote island is well away from the usual shipping lanes and will be a temporary base where the crews, more than three hundred men packed in the two cramped, damp ships, can go ashore to stretch their legs and recuperate from their grueling voyage. Then they will launch a surprise attack on the coast of Chile.

The two captains carry licenses to justify this predatory behavior. Their letters of marque and reprisal, written in florid legal language by government clerks in London, give them leave to harry the enemies of the king of Great Britain. In the year 1709 the Kings enemies include all subjects and allies of the Spanish crown. In return the Spanish regard such raiders as pirates, and use that blunt word to describe them. They also suspect, rightly, that some of the sailors aboard the raiding vessels are ex-buccaneers who have conducted previous hit-and-run raids along the coast of what is modern-day Chile and Peru. If the Spanish authorities can catch them, the luckier ones may be exchanged for ransom, but most will spend the rest of their lives in prison or as slave labor. A few, positively identified for their crimes, will face execution.

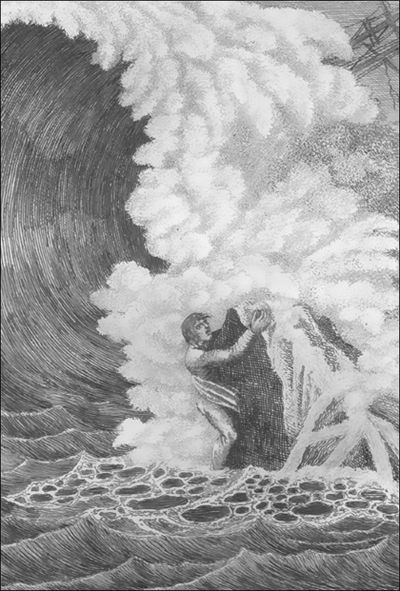

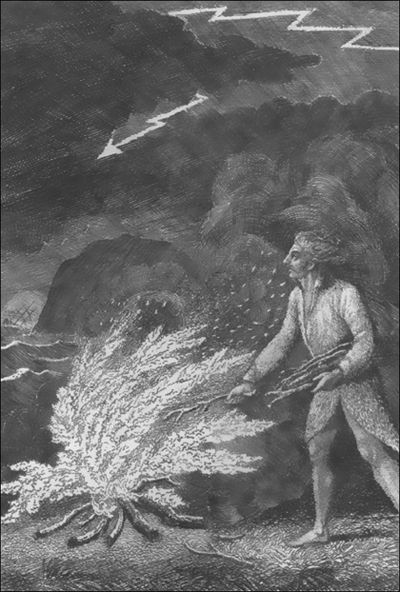

So it is a shock when the ships lookouts spot a light burning on the heights of the island. The two vessels first glimpse the distant outline of land at seven oclock on the morning of 31 January. The island lies to the west of their track, and they immediately turn toward it. But the new course is upwind and neither vessel is a swift sailer. They make such slow progress that by noon the following day they are wallowing through the swell and are still some four leagues from their landfall. Aboard the Duke Dr. Thomas Dover impetuously asks for the pinnace to be lowered and manned so that he can be rowed ashore. His wish is granted because he is one of the English shareholders who invested the substantial sum of fourteen thousand pounds to arm and victual the two ships, and he holds the rank of second captain. Later he will become famous for creating a patent medicine based on opium resin. Dovers Powder will be a stock item of ships medicine chests for the next two hundred years, prescribed for colds, coughs, insomnia, rheumatism, and dysentery. But its headstrong inventor is no mariner. The distance to the island is too far to row. When darkness falls, the doctors boat has still some way to go and the watchers aboard the ships become alarmed. It is obvious that the pinnace will have to turn back and in the darkness may miss the ships altogether. The Duke and Duchess sling lanterns in the rigging to guide home the strays and fire off muskets and a gun on the quarterdeck to help them get their bearings. The lookouts peer into the darkness for signs of the returning boat. This is when they distinctly see a point of light. They think at first that it is a lantern aboard the pinnace, but soon realize that the flare must come from a bonfire on land.

This is very ominous. It had been presumed that there was no one living on the island. A bonfire means human presence. Dr. Dover could not have lit the fire because the pinnace reappears out of the darkness at midnight, and her crew report that they failed to set foot ashore. The obvious explanation for the light is that the Spaniards have garrisoned the island. If so, the privateers risk a fiasco. The garrison could already have sent word to the mainland, warning about the arrival of foreign vessels, and the raiders would have lost the all-important element of surprise. But the Spaniards are not the first foe who spring to mind: England is at war with France, and Woodes Rogers and his officers fear that a hostile French squadron has entered the Pacific ahead of them and taken possession of the strategic island. We are all convinced the light is on the shore, and design to make our ships ready to engage, believing them to be French Ships at anchor, Woodes Rogers writes in his account of the voyage published three years later.

But he also notes that his own ship and the Duchess have a great many Men down with the Cold, and some with Scurvy, and as overall commander of the privateering enterprise he knows that some invalids will die if they are not gotten ashore for treatment. So he has little choice but to proceed with the original plan of landing on Juan Fernandez.