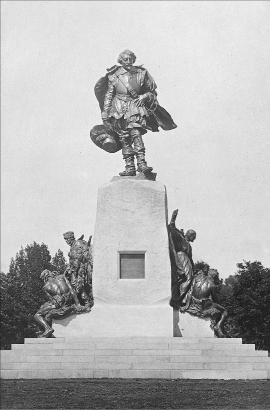

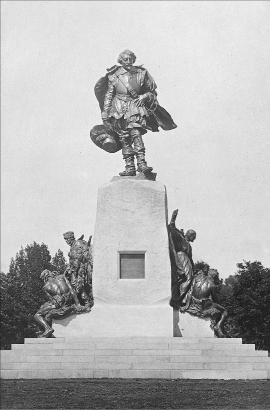

Champlain Monument

The Champlain monument in Orillia, Ontario. It was unveiled on July 1, 1925, at Couchiching Beach Park. Standing at over nine metres high, the monument was created in England by artist Vernon March and shipped to Canada

Archives of Ontario, F1152, Container 3, Series B293935.

4

St. Croix, 1604

While Champlain was completing Of Savages , de Mons was discussing another expedition to New France, one that he would lead himself. He suggested, instead of returning to the St. Lawrence, and the terrible cold of Tadoussac, they might investigate the lands along the Atlantic coast between the 40th and the 45th parallels. The lands south of the 40th were to be shared by Spain and Portugal, a greatly criticized division because it gave too much power to those empires.

FASCINATING FACT

Champlain's Acadia

Champlains first year in Acadia was his greatest mistake.

The St. Croix Island site was a prison and a graveyard for the suffering garrison. Scurvy was the scourge! The white settlers had much to learn from the first nations. The latter might starve from winter food shortages. With dried fruit and corn, and with good hunting, they thrived. As time passed, Champlain found that when Natives cared for the sick, they recovered, and he learned much from their methods. In the spring of 1605, the French began a removal to Port Royal, where the hunting was good. The golden year was 1606, when Champlain kept spirits high in the dreary winter by The Order of Good Cheer.

Acadia failed when de Monss trading monopoly was revoked, and the settlers were ordered to return home.

Champlain liked de Monss recommendation, as long as his friend and mentor could receive a trade monopoly from the king. Samuel also agreed that the part of New France being called Acadia would have a milder winter than the St. Lawrence. They could also search for a more southerly passage to the Pacific that might be shorter. De Mons got his trade monopoly easily enough.

FASCINATING FACT

What Was Expected of the Explorers of New France?

Neither Champlain nor de Mons realized what the governments terms might mean. They did not fully understand the high expectations the French leaders in Paris demanded of men who went to secure a foothold for France in North America. Applicants taking the initiative faced nearly impossible odds. They had to fulfil six conditions:

- To place settlers on the claimed land to defend a French presence.

- To explore the new lands and report on their findings.

- To carry out such expeditions without financial assistance from the government

- To encourage trade.

- To convert the indigenous peoples to Christianity, Catholic rather than Protestant.

- To explore for mines, a source of valuable metals, preferably gold and silver, but copper would be welcome.

De Mons received a monopoly that applied to all of New France, but he still resolved to find out what conditions were like in Acadia. It was more exposed to the Atlantic and more open to visits of fishermen from the Grand Bank, and more vulnerable to actions of the English and the Dutch. Both were searching for a passage to the Pacific. Some voyagers went northeast looking for a route above Russia. In 1597, the Dutch navigator Willem Barents had died after his ship was caught in ice near the sea that bears his name.[1]

Men like the English explorer, Sir Martin Frobisher, pinned their hopes on the northwest. Sir Martin was a vice-admiral under Sir Francis Drake in his 1585 expedition to the West Indies. Frobisher made three voyages, in 1576, 1577, and 1588, to the northeast coast of Canada. He found his way into Hudson Bay, but had no luck going farther west. Frobisher Bay, on the southeast tip of Baffin Island, was named for him. The village at the head of the bay bore his name until the Inuit residents voted to rename their village Iqaluit in 1984.[2]

Champlain may have known Sir Martin, who had commanded a fleet carrying troops sent by Queen Elizabeth I to assist the Protestants in their battle with the French Catholics and their allies. In 1594, Frobisher was mortally wounded fighting a Spanish force on the west coast of France. If Champlain, fighting on the same side, had not met him, he would surely have heard of him or seen him at a distance.[3]

The de Mons expedition, the first successful attempt to start a French settlement in North America, began in 1604. De Mons had asked to be sent as viceroy, or commander, but was refused, although he did fill that role. Champlain thought of himself as a geographer and explorer, but he had no special rank. He was useful also because he believed in the vital importance of collecting fur pelts, and of bringing Christs message to the heathen nations:

In the course of time we hoped to pacify them, and to put an end to the wars which they wage against one another, in order that in the future we might derive service from them, and convert them to the Christian faith.[4]

The expedition set sail from Le Havre in March 1604. Seventy-nine men were on two vessels. One was the faithful Good Renoun and the other was the smaller Don de Dieu . Pont-Grav was in command of both ships. Some of the men were ordinary labourers, or boys as young as 10, but others were skilled and knew how to build a habitation of squared logs. Another nobleman coming to find a place for a settlement was Jean de Biencourt, sieur de Poutrincourt (the latter name for short). Poutrincourt would play an important part in the future of Acadia. Since Catholicism was not yet the official denomination for France, two priests and one minister were aboard.[5]

FASCINATING FACT

Some Key Factors Operated Against Their Success

- Trading, especially in furs, and colonizing were incompatible. Clearing land for agriculture meant a reduction in habitat for fur-bearing animals. Consequently, holders of monopolies usually treated the obligation to bring settlers in lightly. They hoped to get rich quickly, counting on the slowness of travel before an order to revoke a monopoly could be enforced.

- Lack of interest by French leadership. Men such as the Duc de Sully, King Henris prime minister, opposed colonization. He saw all the available money as necessary to rebuild France after the wars of religion that had held the country back. Others merely saw little value in colonies.

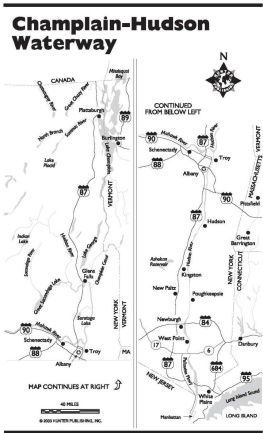

The ships arrived off Sable Island early in May. From that huge sandbar, they sailed westward across the large open sea until they could follow the coast, while Champlain used the time to map and record. With de Mons, he noted stopping places at LaHave (or Heve); the site of Liverpool, Port Mouton, and at the tip of the peninsula (Nova Scotia), was Cape Sable, a fine location for a trading post. They spent the rest of the summer sailing into St. Marys Bay, around and about the Bay of Fundy and into the vast harbour, which was so majestic that they named it Port Royal. Along the north shore (New Brunswick) they went a short distance up the Saint John River, and on to Passamaquoddy Bay, entering the St. Croix River. Champlain was delighted with the appearance of an island he referred to as St. Croix. It would make a fine defensive site if Europeans arrived, or they found the Native population hostile.[6]

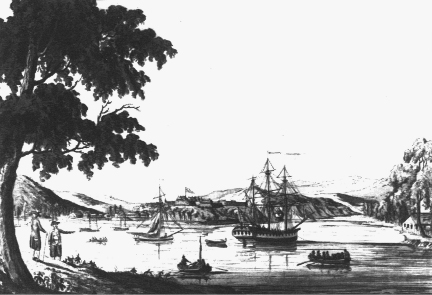

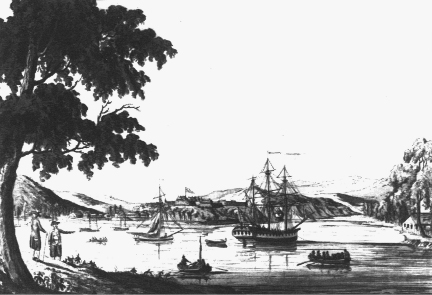

Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. Originally founded by the

French as Port Royal, this harbour and settlement

changed hands many times.