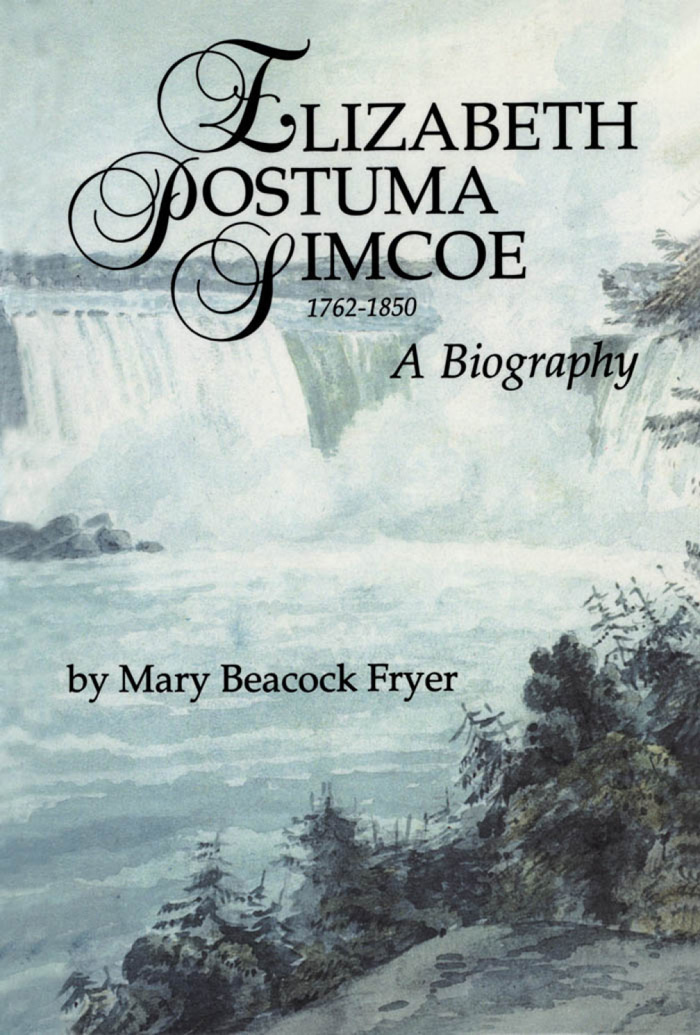

Copyright Mary Beacock Fryer, 1989

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundum Press Limited.

Design and Production:Andy Tong

Printing and Binding:Gagn Printing Ltd., Louiseville, Quebec, Canada

The publication of this book were made possible by support from several sources. The publisher wishes to acknowledge the generous assistance and ongoing support of The Canada Council, The Book Publishing Industry Development Programme of the Department of Communications, and The Ontario Arts Council.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in the text (including the illustrations). The author and publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any reference or credit in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, Publisher

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Fryer, Mary Beacock, 1929-

Elizabneth Posthuma Simcoe

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-55002-063-3 (bound). ISBN 1-55002-064-1 (pbk.)

1. Simcoe, Elizabeth, 1762-1850. 2. Ontario - History - 1791-1841 - Biography.* 3. Ontario - Social life and customs. 4. England - Social life and customs - 19th century. I. Title.

FC3071.1.S5F78 1989 971.3'02'092 C89-090704-8 F1058.S7F78 1989

Dundurn Press Limited | Dundurn Distribution Limited |

2181 Queen Street East, Suite 301 | 73 Lime Walk |

Toronto, M4E 1E5 | Headington, Oxford |

Canada | EX3 7AD |

England |

INTRODUCTION

Had she not spent five years in Upper Canada (now the Province of Ontario) as the wife of the first lieutenant governor, Elizabeth Simcoes many diaries and letters would have been of interest mainly to her descendants. In Ontario today, and to a much less extent elsewhere, Elizabeth is best remembered for the record she wrote while in Canada for her family and close friends who remained in England, and for the informative water colour sketches she made of the country through which she travelled.

The first person to investigate Elizabeth Simcoes life outside the province of Ontario was the newspaper publisher John Ross Robertson. His version of Mrs. Simcoes diary was first published in 1911. Later authors, Marcus Van Steen and Mary Quayle Innis, accepted many of Robertsons assumptions and built upon them. In more recent years Hilary Arnold of York, England, became interested in Elizabeth Simcoe and did her own exploring. She found a different date and place of birth, and she has unearthed considerable information about Elizabeths entire family, information that differs from the accepted version. Hilary has been very much my collaborator, and her lengthy genealogy on Mrs. Simcoe forms an impressive appendix to this work.

Edith Firth, formerly with the Metropolitan Toronto Library, contributed the account of Mrs. Simcoe to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. She discovered that there are at least three versions of the Canadian diary; the first is short notes on which Elizabeth based the other two. The second she sent to Mrs. Ann Hunt, who was in charge of the children who were left in England; the third was for her dearest friend, Mary Anne Burges, in which she enlarged her detail on flora and fauna of Upper Canada. The version John Ross Robertson used was a combination of the latter two. Apparently some of the Simcoe family added details from Mary Anne Burges version, because in places Elizabeth was answering specific questions which her friend had asked her. Of the two children who accompanied the Simcoes to Canada, Elizabeth says almost nothing about her daughter Sophia, except in her short notes or in letters to Mrs. Hunt and Miss Burges. The diary, as published by Robertson, has more detail about Francis, because Miss Burges asked Elizabeth to tell her about the boy. The parts relating to him have been added from the version Elizabeth sent her friend, probably by her daughters after Francis premature death. Many sources other than Robertsons reveal more of Elizabeth Simcoes life than the disclosures in her Canadian diaries details on her early life, on the lives of her children while she was in Canada, and on her life and those of her children after the family had been reunited in England in 1796. One extensive collection is in the Devon Archives, and copies of this material are on microfilm in the National Archives of Canada in Ottawa. The other is the Ontario Archives Simcoe Collection, which does not pertain to Canada.

The letters and diaries unveil a world that in some ways resembles that portrayed by Jane Austen, Elizabeth Simcoes contemporary. Both women are formal in their way of addressing others. Elizabeth gives no indication that she ever called her husband John: she used his military or other rank. In his letters to Elizabeth, Simcoe addresses her as My most Excellent & noble wife or in similar phrases, but in one poem to her he calls her Eliza.

Elizabeth reveals little of her inner self in her Canadian diaries, and not very much in her letters to friends and relatives. This is true, too, of the letters written by her children. The education all received schooled them in a particular form of letter-writing that was polite, informative, rarely emotional, and following rigid conventions. Mary Anne Burges letters are much more personal; she relays most of the conversations used, while the others are based on sources. No conversation is invented.

The events of Elizabeth Simcoes early life help explain her apparently cheerful acceptance of conditions of life and travel in the Upper Canada of the 1790s. Her life spanned four reigns, two of them remarkable for their longevity. Elizabeth was born in the early years of the reign of George III, lived through those of George IV and William IV, and she saw the first fourteen years of the Victorian era. In her youth she travelled by coach, chaise or on risky sailing ships. Before her death, steamships plied inland waters and oceans, and railways were extending their tentacles across England and North America. Always interested in anything new, she mentioned acquiring an electric motor. She did not, as John Ross Robertson assumed, live in seclusion after the death of her husband. She was, by the standard of any era, a lively, involved, active person all her life. Yet she was the product of the late eighteenth century, and an early representative of the genteel woman who accompanied Britains colonial administrators to the outposts of empire. What James Morris wrote of the Honourable Emily Eden in