Paolo Rumiz

THE FAULT LINE

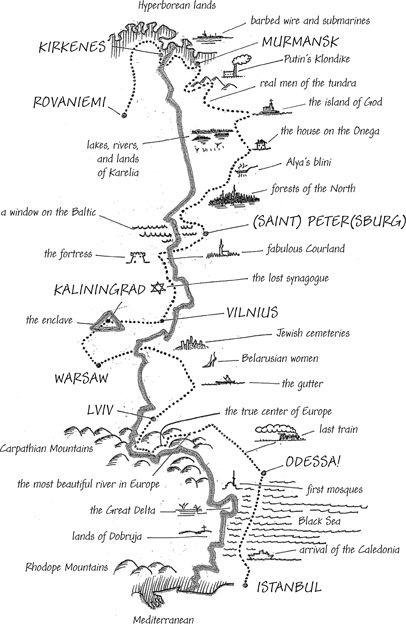

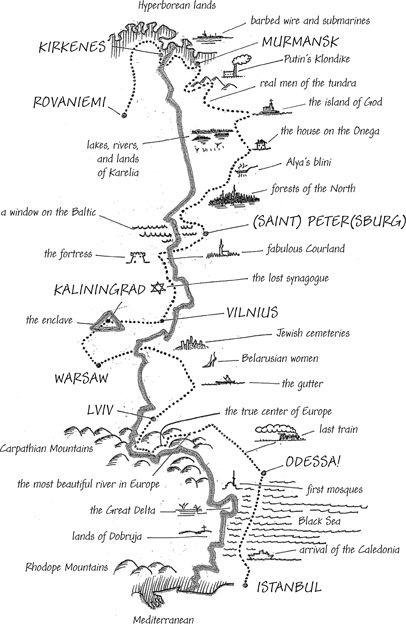

TRAVELING THE OTHER EUROPE, FROM FINLAND TO UKRAINE

You always go back to the scene of the crime. I suppose thats why on a rainy day in January 2014, I set out again for the land of rivers, lakes, and forests that I had traveled through six years earlier on my unforgettable vertical journey along the eastern border of the European Union. To blame for my return was the First World War. One hundred years had passed since it began, and I had realized in amazement that the line of its endless Eastern Front coincided in many placesthe Baltic countries, Masuria, Ukrainewith my 2008 itinerary.

The conclusion was almost automatic: the frontier of the European Union was not only located in the heart of Europe; it was also on a ruinous fault line.

Now, because earthquakesincluding those of the geopolitical varietytend to strike repeatedly in the same places, that long-term historical perspective inevitably consolidated the intuition expressed at the time I wrote this book, that a new Iron Curtain was forming, a few hundred kilometers east of the old one, which had collapsed in 1989. It now seemed even more plausible that countries like Ukraine, still Austro-Hungarian in the west and Russian in the east, were destined to be split in two, with grave consequences for the peace of the continent and the internal equilibrium of the Union.

This was confirmed by the events of 2014 in Kiev and its surroundings. By pure coincidence, the Ukrainian revolt exploded right before my eyes during my return to the Carpathians, changing all my perceptions. From then on, it was no longer possible to limit myself to the past, because the force of events obliged me to look at the present. Everything started to fit together like a puzzle. What I saw, for example, in the freezing-cold train station in Lviv, beyond the Carpathians, matched what I had been told in 2008, almost as a prophecy, by the student Maxim at the station in Khmelnytsky. A new conflict was in the offing, the country was on the verge of implosion.

Unlike my original vertical journey, my return to those places took the more banal form of a horizontal trip along the east-west axis of the great European roads, the rail lines, and the historic routes of armies. My aim was to verify, by navigating along the parallels, the findings I had made during that earlier extraordinary north-south core sampling. But the means of penetration remained the same: public transportation, particularly trains. They were not only a means for reliving the troop movements toward the front in 1914; they were also a good seismograph of the present. To understand which way the world is heading, you have to go to train stations, not to airports. But because diplomats prefer airports, their governments are no longer capable of foreseeing events.

I started out from Hungary, my staging area. There I sniffed the scent of a landlocked nation, proudly shut in on itself and haunted by claustrophobic nightmares. Budapest, nebulous in the endless Pannonian night, was the oversize head of a country whose body was reduced to its minimum dimensions a hundred years ago by the cynicism of Western politics. I remembered the solidity of the housesstill Hapsburgianand its grandiose architecture, more monumental than Viennas. Everywhere I looked, what came afterward was nothing more than a miserable crust. Everything indicated that 1914 had marked the beginning of a great unhappiness, which still endured today. Anti-Semitism was fatally reemerging, and peoples minds were focused on the past. Politicians couldnt stop haranguing against the injustice of Versailles, the peace treaty that had deprived the country of two thirds of its territory.

The only way back to Ukraine was the night train for Moscow, a noble, snail-paced convoy of sleeping cars, which at the border with the former Soviet empire still had to stop, as it did in Brezhnevs time, to adapt the cars to the different gauge of the Eastern tracks. The instant I boarded, I felt as though I had entered a magnificent time machine. We headed into the pitch-dark plain, and from then on, everything became diluted and unfathomable. I saw armies marching blindly, searching for the enemy in the immense void of the steppe. The exact opposite of the Western Front, immobile in the trenches, concentrated in a narrow strip only a few miles wide. The Eastern Front was still the land of the Scythians and the Budini, the ancestors of the Slavs, whom the Persian emperors Cyrus and Darius had vainly attempted to rout on the boundless plains around the Black Sea.

I noticed that the Russian train personnel were gruff with foreigners and especially with the conductor of the only Ukrainian sleeping car. The reason was immediately clear to me: Kiev had seen the first incidents of street fighting that would shortly brew into a revolt, with people dead and wounded. The news was already racing from mouth to mouth; it had arrived on the wire of those cars and those tracks. Down at the end of the corridor, the conductor of our sleeping car was busy making tea in the samovar on the coal-fired stove, and I was reading the notes made by the soldiers on their way to the front: Its all mud, mud, mud. Mud in the water, in the air, on the roads, in the pastures, in the fields, everywhere. Even the people look as though theyre made of mud.

At midnight it was time to stamp passports, check visas, and inspect baggage.

Then we heard the sound of hammer blows, screeching wheels, rattling chains, jacks. The cars were raised up one by one, and dozens of railroad workers appeared out of the rain to toil under the belly of the train. When the train started back down the track toward the Carpathians, trying to find its way in a thunderstorm, I heard the sound of the road to perdition, the same sound heard by the boys of 1914 and, thirty years later, by the armies of the great totalitarian regimes, and then by millions of civiliansJews, Germans, Gypsies, Poles, Ukrainianstorn from their homes and condemned to exile or extermination.

We were moving slowly, uphill, through ramshackle villages whose walls looked like papier-mch, past lighted cemeteries and the ruins of collective farms, toward a dawn that was like a long howl. As the train panted its way up the mountainsides, the radio transmitted the latest news of the revolt, and that revolt, superimposed over my reading, evoked the same enemy: the legendary Golden Horde, the freezing cold of shelterless winters, the terror of the Cossacks gallop, the vast armies of the czar. Forests, slow-moving rivers, sleet, reverberating bridges between Christian villages and the shtetls of the extinct Ashkenazim. I saw the locomotive winding through the brush, leaning to the right, and the line of cars following it with their magic-lantern windows. I was traveling in a different time, inside an archipelago of woods and downtrodden villages, with churches and ruins of synagogues, whose roofs were capsized boats.

Then, out of the cold and mud came Lviv, all of a sudden, with the meringue-like domes of a bonbon city and the iron roof of its old station. Those Hapsburgian domes, those Jugendstil wonders, which went into hibernation during the Communist winter, confirmed what I had understood in 2008. I was not at all in the East, but in the heart of the continent, in that Mitteleuropa that a great multinational empire, torn to pieces by the peace treaty of 1919, had governed with wisdom, avoiding ethnic conflicts and assuring the various peoples of Europe a providential buffer between East and West. Lviv could have been Prague, or even Trieste. I could see their common ancestry in the dormer windows, the trollies, the hot chocolate, the cafs of old Austria, the snow-sprinkled onion domes, the portraits of Kaiser Franz Joseph hanging once again on the tavern walls. No doubt about it, the Europe that I loved was still holding firm in the provinces, not in the great urban centers like Rome or Frankfurt. It was in places like this, on the margins of the Union and perhaps even outside its borders. I could feel it in Lviv just as I could in Odessa, Riga, or Lublin. It revealed itself in the oldstyle faces of the people, in the terrible secrets of the 1940s, in the uprooting of its peoples and its lost Judaism, but also in the peoples nostalgia for honest politics and in their desire for a West, which as usual showed itself incapable of understanding. Never so much as in Lviv had I realized that the land of the single currency was losing its soul, sleepwalking in the theater of the new instabilitythe same somnambulism that in 1914 had sent Europe plunging into a war that nobody wanted.