GHOST TOWNS

LOST CITIES OF THE OLD WEST

Clint Thomsen

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

Benson Grist Mill built in 1854, with farm equipment and the ruins of the Lee Tannery and Summerhays Wool Pullery in the foreground, E.T. City/Richville, Utah.

CONTENTS

Bannack Masonic lodge and schoolhouse, side view. (Photo Patty Pickett)

Ruins of the three-story John S. Cook and Co. Bank, in Rhyolite, Nevada. The second floor housed brokerage offices and a post office. (Photo Daniel Ter-Nedden /www.ghosttowngallery.com)

INTRODUCTION

Here is only silence now gone the hopeful, thronging host that left these walls, in haste to go, left these streets to wind and ghosts.

Author unknown

I T WAS LONG PAST SUNSET when my friend, John, pointed his four-wheel drive toward the San Francisco Mountains and rolled onto the rutted dirt road. After five hours on the road, we had finally reached the land of the Silver Horn Mine. Somewhere in the darkened hills ahead were the remains of old Frisco, the long-deserted commercial center of the San Francisco Mining District and southwestern Utahs most notorious boomtown.

My friend Tyler sat next to me while we analyzed our maps by flashlight. I combed through my packet of compiled information on Frisco, reading aloud for dramatic effect the comparisons of the town to the raucous Dodge City, Kansas, and the biblical city of Gomorrah. Frisco wouldnt be our first ghost town, but it was the best-documented, most-storied town we had sought out thus far. We could hardly contain our excitement as Johns headlights finally caught the tips of several wooden crosses in the towns cemetery.

These modest posts marked many of the cemeterys forty-two internments. Some graves were evidenced only by an oval ring of rocksa hallmark of mythic western imagery. More prominent plots were neatly fenced with barely legible headstones. Further down the road were the crumbling relics of the town that by the mid-1880s supported a population of more than six thousand silver miners, gamblers, gunslingers, and other characters. We spent hours studying rock walls and tracing foundation lines before rolling out sleeping bags on the alkali ground and drifting into dreams of the past.

Abandoned places have always occupied a special spot in the human psyche. From the religious to the recreational, our compulsion to commune with the past is deeply intrinsic.The concept of heritage colors most visited on earth. In the New World, few symbols are as iconic as the American ghost town.

Street scene in Frisco, Utah, date unknown. (Used by permission, Utah State Historical Society, all rights reserved.)

An estimated forty thousand ghost towns pepper the American landscape in various states of decay. A sampling of their names connotes a colorful, frank era: Toadsuck, Big Bug, Two Guns, Deadwood, and Tombstone. There was Virginia City, Nevada; Virginia City, Montana; and Virginia City, Arizona. Naturally, the words gold and silver found their way into thousands of boomtown names.

S. N. Slaughter General Merchandise store with women standing on the raised plank porch, circa 1884. (Used by permission, Utah State Historical Society, all rights reserved.)

Some ghost towns, like Frisco, are legendary. Most, like Cloud Chief, Oklahoma, are not. Many have all but returned to the dustthe inevitable victims of time, looting, or development. Some remain partially alive, existing in an odd, yet charming postbust limbo. A precious few have been preserved as open-air museums. Parts of others still stand in near pristine condition due to their extremely remote locations.

Ghost towns span such a broad spectrum of time and geography that a comprehensive approach here would dilute the various types. For most people, the term ghost town evokes images of mining camps and wooden false-front buildings typical of the American West. Thus, this book focuses on the ghost towns of the western United States, with particular emphasis on those with roots in the Old West era.

What exactly is a ghost town? How did they rise? Why did they fall? What can their remains tell us about the people that once called them home? And how can they be experienced today?

Many publications on the topic fit one of two molds: art-driven photo books and statistic-heavy travel guides. The former inspires visually but tends to be short on information. The latter is sufficiently informative, but is naturally date-sensitive. Over time, sites are reclaimed, destroyed, picked over, and in some cases thoroughly reincarnated. Furthermore, the accessibility of many sites evolves as land changes stewardship. A site that was publically accessible in 1994 may be completely off limits in 2012.

Buildings in Bodie, California. (Photo Joe Decker/Rock Slide Photography)

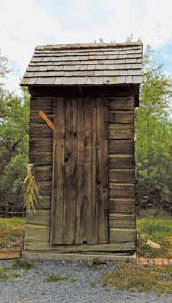

Historic outhouse on display at the Benson Grist Mill, E.T. City/Richville, Utah.

This book shuns both templates. Instead, it explores the larger ghost town phenomenon and our evolving interpretation of it. traces the history of the ghost-towning hobby and offers tips for experiencing ghost towns today.

The issue of population merits special note. Determining historic population counts for ghost towns is often problematic due to several factors, including the occurrence of population peaks between census counts, the difficulty of accurately enumerating a towns transient population, and the tendency of some writers to attribute the population total of a mining district to its commercial center. Population counts included in this book reflect official U.S. Census numbers wherever possible. Otherwise, totals are either calculated or estimated based on best-known sources.

Artifacts on display at the museum in Jerome, Arizona. (Photo copyright leonids.us)

Stairwell in Hotel Meade, Bannack, Montana. (Photo Patty Pickett)

Street in Bannack, Montana. Founded in 1862, Bannack is often praised as one of the Wests most photogenic ghost towns. (Photo Patty Pickett)