The Arts of India: APPROACH

B EYOND THE HIGHLY CIVILIZED CITIES OF HARAPPA AND Mohenjo-daro in the Indus valley, which flourished some five thousand years ago, traces of palaeolithic and neolithic culture have been found in many parts of India. The rock shelters of central and northern India are now known to be repositories of the earliest manifestation of pictorial art in this subcontinent. Standing out dimly upon the rough walls of these caves are seen drawings of animals and men generally representing hunting scenes and other group activities. Numerous rock paintings discovered at such places as Singanpur, Mirzapur, Hoshangabad, are strongly akin to the prehistoric cave paintings of Spain.

The hunting scene in Singanpur cave, where a group of hunters is struggling to capture a bison, is a forceful presentation in mauve, pale yellow and burgundy. A similar scene in Mirzapur cave depicts the death agony of a wounded boar. Although many of these rock paintings are now undecipherable, and some having been covered by later drawings, enough is preserved to testify to the dynamic vision of the prehistoric artist.

Our knowledge, however, of this earliest art form, with all the fascination it offers, remains embryonic. But the art of the Indus valley is at once more familiar and comprehensive. The clear and coherent conceptions of plastic art which confront us for the first time at Harappa and Mohenjo-daro are undoubtedly the culmination of artistic traditions of centuries.

This was the turning point and with it Indian sculpture in the proper sense began. And it began with such a rich promise that Rene Grousset, while studying a Mohenjo-daro earthenware statuette of a seated monkey, remarks that "it may well foreshadow the whole art of Indian animal sculpture, from capitals of Asoka to the ratha of Mavalipuram." It is not in animal forms alone that the art of Indus valley anticipates the subsequent development of Indian sculpture. Among the many small fragments of sculpture so far discovered in these sites are figures of a dancer and a dancing girl and a small torso of plastic subtlety. These statuettes bear witness to the ease and certitude with which the artist of the Indus valley handled the various plastic mediums like terracotta, ivory, bronze and alabaster.

Unlike their contemporaries in Egypt or Babylon, the Mohenjo-daro artists did not go in for the spectacular. They did not evolve a monumental art. No temples or palaces which point to a dominant kingship or priesthood have been found in the cities that have been explored. Perhaps social life and religious expression in the Indus valley civilization did not demand such art forms. But there are public baths, granaries, well-constructed houses, wide thoroughfares, and an intricate system of drainage which speak of an expansive and dignified civic life.

Art in the Indus valley, therefore, was conceived on a scale in which it could belong to the life of the people. The host of terracotta figurines, symbolic of a matriarchal culture, with their freshness of primeval joy, are representative of a folk tradition and link Mohenjo-daro with the prehistoric world. Most of the female figures center around fertility. But in the absence of attributes, one does not know whether they stand for goddesses or human beings.

The mother and child group expresses a subconscious notion of the potential powers of woman. There is a total disregard for accuracy in anatomical details, but in each case the figurine is full of life, possessing a natural, quiet distinction, and a pride of fulfilment. The enigmatic expression of the mother gives her a feeling of a mysterious withdrawal; the rather compressed mouth and strong, queer, arched brows reveal an immobility which is the primeval root of all beauty. Another innate virtue of the primitive mind, sensitiveness to color, expresses itself in endless varieties of illuminated potteries so abundantly found in Harappa and other Indus valley sites.

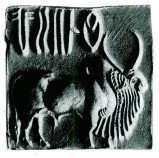

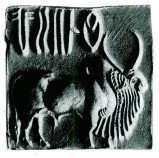

B. Indus Valley Seal

Of particular interest are the engravings on the seals that have been found in large numbers in Mohenjo-daro. The pictographic script which appears on some may eventually provide a clue to their use, but has not yet been deciphered. The subject of the engravings is usually an animal, the types most frequently represented being the humped or Brahmani bulls and unicorns. In the exquisite modeling of the bulls, the majesty and restrained vigor of the beast are strikingly conveyed. They are so successfully animated as to impart life into the figures which have otherwise a sphinx-like serenity.

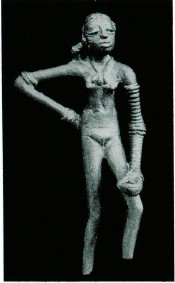

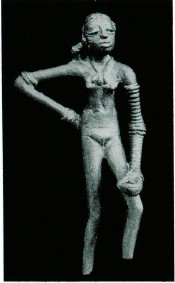

Further, though sculpture of the human figure in the round has rarely survived, what has survived bears witness to the sense of volume characteristic of mature sculpture. This is illustrated at its best in the limestone statuette of a nude dancing figure from Harappa. The warm and lively body of a young male, revealing himself in contour, had never probably come so true in the medium of stone. Another illustration of this type can be found in a bronze statuette of a nude dancing girl from Mohenjo-daro. The sensitive molding of her back, the tense poise of her legs, are most significant. "But above all," says Iqbal Singh, "in the subtle comprehension of the dynamic expression which forms, as it were, an invisible background to her whole frame, plastic representation achieves a quality of perfection hardly surpassed even by the medieval South Indian bronzes."

The period is further marked by the emergence of phallic emblems, which indicated a growing male awareness that the source of generative power is the father, until then so long regarded as just a "way-opener." The discovery that male semen impregnates the female provided an important basis for the rise of the phallic cult, not only in India but most probably throughout the world. Even an anthropomorphic representation appears to be embodied in the figures of Pasu-patinatha seated in a yogi pose, found at Mohenjo-daro, which is probably a direct predecessor of the later popular and powerful deity Siva, whose cult is closely associated with that of the lingam phallic symbol.

The Indus civilization did not collapse, as we commonly think, sometime about 2000 B.C., but was assimilated in successive stages of Indian life and thought. Although aesthetic history during the following fifteen centuries remains shrouded in mystery, and our lack of knowledge about any archaeological store of this period is unfortunate, we can be sure that the people who dwelt in India during those centuries were certainly no idlers.

Vedic burial mounds at Lauriya-Nandangarh and other places, which may be placed around 800 B.C. or thereabout, have yielded, among various objects, a small gold plaque bearing the figure of a nude female, probably the earth goddess mentioned in the burial hymns. A few more terracotta figurines of similar antiquity have also been found at Taxila, Bhita and other sites. The technique of execution is the same as in the Indus valley and the figurines have a close affinity which suggests a continuity in art traditions. Though very few in number, they are of vital significance insofar as they provide the only link between the products of protohistoric age and the subsequent periods.

C. Bronze from Mohenjo-daro

Literary evidence shows that the Vedic people were also experimenting with symbolic expressions that bore the transcendental excellence of their thought and emotion. Their attainment in meditative philosophy stands out even today as the finest ever achieved by man. For instance, the Rig Veda, the oldest Hindu scripture compiled as early as 1500 B.C., reveals a knowledge of the awakening of the human soul and its eternal inquiries into the mysteries of the universe.