By the same author

FICTION

Ofay

The Boots of the Virgin

Under the Fifth Sun

NONFICTION

The Death of the Great Spirit

The Oppressed Middle/Scenes from Corporate Life

Jews without MercyA Lament

Power Sits at Another Table

While Someone Else Is Eating (editor)

Latinos: A Biography of the People

Parts of this book, in an entirely different form, appeared in Harpers Magazine. Lines from The Man With the Blue Guitar by Wallace Stevens reprinted from COLLECTED POEMS by Wallace Stevens. Copyright 1936 by Wallace Stevens and renewed 1964 by Holly Stevens, reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

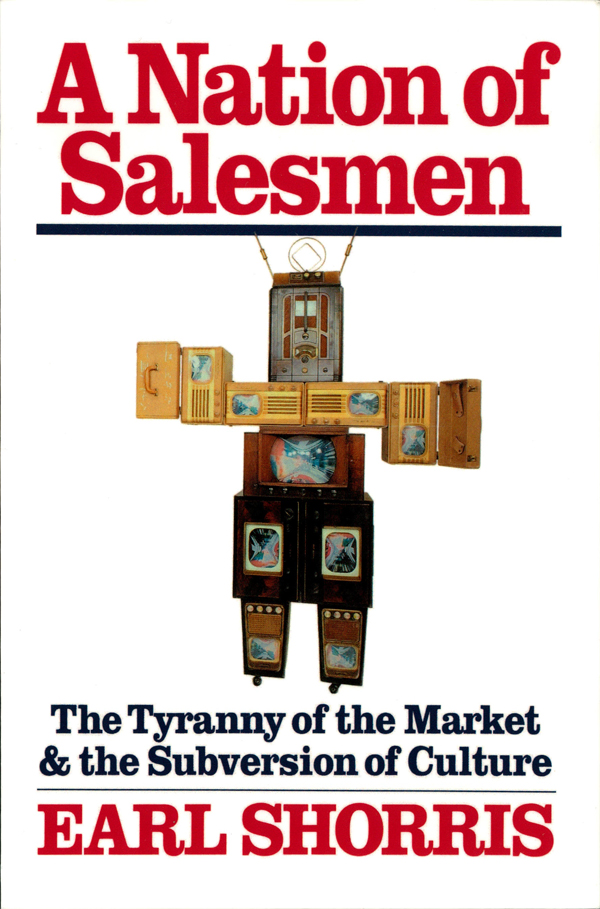

Copyright 1994 by Earl Shorris

First Edition

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The text of this book is composed in Galliard with the display set in Galliard Bold Composition and manufacturing by the Haddon Craftsmen, Inc. Book design by Jacques Chazaud

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shorris, Earl, 1936

A nation of salesmen : the tyranny of the market and the subversion of culture / by Earl Shorris.

p. cm.

Includes index.

1. SellingUnited StatesHistory. 2. SellingSocial aspects United StatesHistory. 3. SalespersonnelUnited StatesHistory.

I. Title

HF5438.25.S563 1994

381.0973dc20 94-16580

ISBN 13:978-0-393-33408-1

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 10 Coptic Street, London WC1A 1PU

For

Cynthia and Maria

The Plan of the Book

A writer who chooses a distant subject has the privilege of doing an explorers work. He sets out on a journey into unmapped territory, guided only by curiosity and some strategy to keep from going around in circles. The writer as stranger expects insight to grow out of incessant surprise. Like an ancient Greek, he believes Wonder is the mother of thinking.

When the subject reaches out of personal history to choose the writer, a different kind of journey takes place. The writer travels the most familiar territory, guided only by curiosity and the hope that he will have the courage to keep his eyes open. The work is bound to be a kind of confession, one in which the writer must expect that every insight may also be an embarrassment.

This book undertakes both journeys, for I have had two careers, one as a writer and the other as a salesman. The writer has, of course, chosen to explore the salesmans territory, but the salesman has also chosen the writer. Considered in its best light, this provides a binocular view of the subject, with all the metaphorical depth such a view offers. On the other hand, there is the possibility of an ethical schism: the application of one set of rules to the personal experience and another, more rigorous ethics to researched material. The reader should be alert to the possibility that for the sake of comfort I may have fooled myself now and then.

As part of the binocular structure, there is a story at the beginning of each chapter. The stories depict the salesman in his daily life. They contain no theories, no facts or figures. I use the stories as a matter of prudence, because I think there is some danger in writing essays that do not include stories or other kinds of reportage: One risks losing the world and all of its precision.

The stories that begin the chapters are fictions, although some of them have a worldly double. One is perhaps my father; another is likely me. I have presented these doubles in deep disguise, not solely for legal reasons but to avoid deception. Fictions, as everyone knows, can never deceive, because lies presented as such are always true.

Sources

Since there is very little good data, other than novels and plays, on the various aspects of selling, I have had to rely in large part on what I have seen and been, like an anthropologist looking into a mirror. In addition to many direct observations, the book uses some personal experiences, not all of them flattering to the author.

The experiences began in 1958 and continued into the 1990s. Although the companies I knew best were AT&T, N. W. Ayer, General Motors, and the Matson Navigation Company, I had the opportunity to study selling with many organizations, both large and small, either as an employee, an agent, or a consultant:

Air New Zealand, American Broadcasting Co., Ball Corp., Bank of Tokyo, Best Fertilizers, Campbell-Ewald, Carrier, Chemical Bank, Citicorp, Dailey & Assoc., Dana, Del Monte, Democratic National Committee, Du-Pont, Edison Electric Institute, Feders Jewelers, Federal National Mortgage Assn., First Boston Corp., Fletcher Richards Calkins & Holden, Folgers Coffee Co., Fuller Paint, KROD, KTSM, Kennedy Hannaford Co., Morris Plan of California, Northern California Chevrolet Dealers, Pacific Area Travel Assn., Procter & Gamble, Pureta Sausage Co., Ramsey Clark U.S. Senate Campaign, Sanders Co., Spare Tire, Sutro & Co., Tar-Gard, Toshiba, Triangle Publications (TV Guide), and, early on, many small retailers.

Thesis

The thesis of this book, that selling has become the determinant activity in the United States, is not complicated. The questions raised by the thesis are plain to see: If America is a nation of salesmen, who are we, each and all of us together, and are we the people and the nation we hoped to be?

The exploration of any idea about a society, even an uncomplicated idea, requires that the idea be defined analytically and historically, and then considered in relation to the politics, economics, culture, and character of the country. That is the business of the book, causing it to be divided into three parts: The first part takes up definitions and history, the second is about selling and how the United States became oversold, and the third examines the way in which the imperative character of selling in the last half of the twentieth century has caused people, especially in America, to have a new view of themselves, their freedom, and their dignity.

Of God and Gender

Gender figures among the more discomforting inconsistencies of the English language, but it neednt have been that way. The language would have been a little bit less specific and a lot less problematical if it had been, like the languages of the Maya of Mesoamerica, almost entirely androgynous. Or it could have been like a Romance language, in which everything that can be named has gender, based on both primary and secondary sexual characteristics, the secondary sexual characteristic of a word being its initial letter. Agua, the Spanish word for water, ends in a, which makes water feminine, but it would be so awkward to say la agua that the rules of the language have given it, and many words like it, special dispensation. Agua is masculine, el agua. Using the same rule of graceful relations, mano, which has a masculine ending, is feminine, la mano.

Can the word salesman be neutered or made androgynous without violating the rule against awkwardness?

There are many possible alternatives: salesperson, seller, vendor, purveyor. Or salesthem, as in the improper use of a plural pronoun to avoid the issue of gender. A complete gender change operation produces saleswoman, saleslady, salesgirl, salesmiss, salesmissus, salesmiz.

None of these will really do, however, for the salesman is now often an advertisement, printed, broadcast, or written in the sky and placed before the potential customer. Any name given to the person who sells will have to apply as well to the thing that sells. Personification is a problem. If one turns to comedy, following the example of

Next page