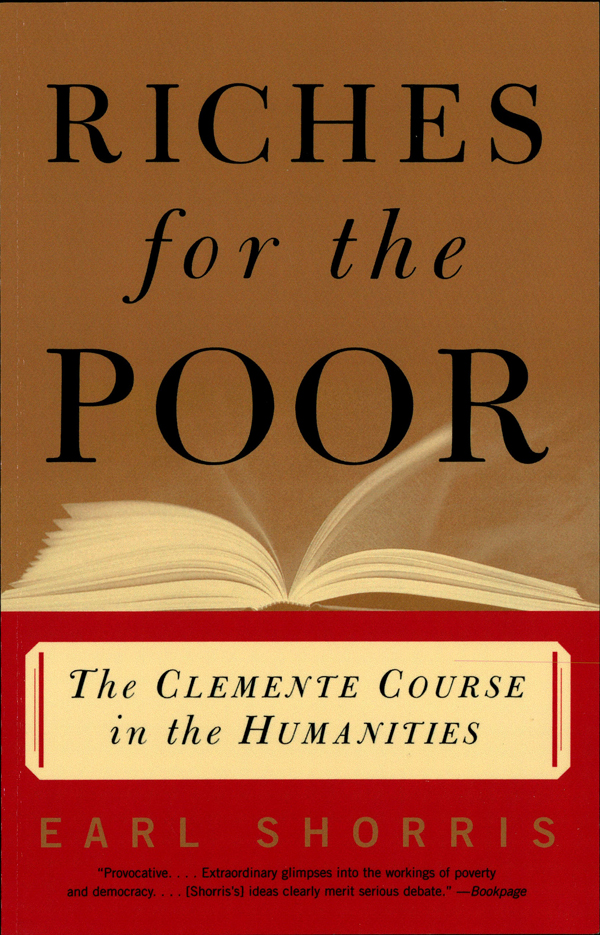

FICTION

Ofay

The Boots of the Virgin

Under the Fifth Sun: A novel of Pancho Villa

In the Yucatn

NON-FICTION

The Death of the Great Spirit: An Elegy for the American Indian

The Oppressed Middle: Scenes from Corporate Life

Jews Without Mercy: A Lament

Power Sits at Another Table: Aphorisms

While Someone Else Is Eating (editor)

Latinos: A Biography of the People

A Nation of Salesmen: The Tyranny of the Market and the Subversion of Culture

New American Blues: A Journey Through Poverty to Democracy

This book is dedicated to

my intrepid museum-going companion Tyler Sasson Shorris;

it is indebted to

our professors and social service providers

and most especially to Martin Kempner, Leon Botstein, and Robert Martin.

Sylvia Shorris was there at the birth of this project

and she has been there every day since;

it was she who suggested the course be offered

to American Indians and Alaska Natives.

Mr. Rich Man, Mr. Rich Man, open up

your heart and mind.

Mr. Rich Man, Mr. Rich Man, open up

your heart and mind.

Give the poor man a chance, help stop

these hard, hard times.

BESSIE SMITH

The Clemente Course in the Humanities has continued and grown thanks to the interest and support of

The National Endowment for the Humanities and the state

humanities commissions of Alaska, Florida, Illinois, Massachusetts,

New Jersey, Oklahoma, Oregon, Washington, and

Wisconsin

The Fund for the Improvement of Post-Secondary Education of the

U.S. Department of Education

The Open Society Institute

AKC Foundation

Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Division of

Juvenile Justice

Alaska Rural Community Action Program (RuralCAP)

Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative/Alaska Federation of Natives

Kenneth and Marleen Alhadeff Charitable Foundation

Brooklyn Union Gas (KeySpan)

CBS/Westinghouse

Centro de la Raza (Seattle)

Cherokee Nation

Cherokee National Historical Society

Chevak Traditional Council

Childrens Board of Hillsborough County, Florida

The Door

Fales Foundation Trust

Grace Jones Richardson Trust

Hearst Foundation

Hispanic Federation of New York

Instituto Technologico y de Estudios Superiores de

Monterrey-Campus Morelos

Darv Johnson

John S. and James L. Knight Foundation

Kongsgaard-Goldman Foundation

Starling Lawrence

Stephen and May Cavin Leeman Foundation

Library of America and Lawrence Hughes

Henry Luce Foundation

J. Roderick MacArthur Foundation

Middlesex County Economic Opportunities Corp.

Marilyn and Philip Napoli

Anne Navasky

New Jersey Community Services Block Grant

New York City Board of Education

New York State/OASAS

New York Times Foundation

Northside Mental Health Center (Tampa)

Martin and Anne Peretz

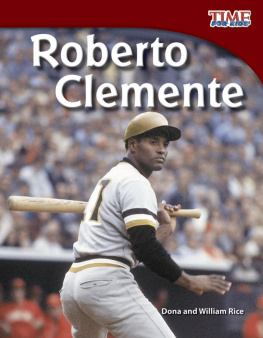

Roberto Clemente Family Guidance Center

Daniel J. and Mary Ann Rothman

Tucker Anthony Incorporated

United Nations Development Program (Yucatn, Mexico)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Head Start Quality

Improvement Grant

Universidad Iberoamericana University Community Resource CenterTampa

University of Alaska at Anchorage

University of British Columbia

University of South Florida

W. W. Norton & Company

Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities at the

University of Washington

Tom and Margo Wycoff

Yupiit School District, Alaska

A CCORDING TO ISAIAH BERLIN, Alexander Herzen had a natural gift for criticisma capacity for exposing and denouncing the dark sides of life. And only a few paragraphs later, Berlin added, As if to restore the equilibrium of his moral organism, nature took care to place in his soul one unshakable belief, one unconquerable inclination. Herzen believed in the noble instincts of the human heart.

This work seeks to offer an explanation of long-term poverty by placing the unfairness of force, the dark side of human life, in contrast to the inclusiveness of legitimate power, which is one of the noble instincts of the human heart. It examines and denounces the dark side and suggests a triumph of the noble instincts.

I.

Richer Than Rockefeller

I N AUTUMN OF 1999, more than four hundred students attended the Clemente Course, a rigorous, university-level course in the humanities. It was not what the world had expected of them, nor what they had expected for themselves. They were all poor, most worked at low-paying jobs, some collected welfare, some were homeless, some had been to prison, more than a few were single parents. Many had not completed high school.

The majority of the students lived in cities: New York, Seattle, Anchorage, Philadelphia, Tampa, Vancouver, Los Angeles, Poughkeepsie, New Brunswick, and Holyoke. Others lived in remote villages in the Yucatn and the Yukon/Kuskokwim Delta. The students were mainly young adults, most of them in their twenties, and even though they were poor, untrained and uneducated, they now entertained the possibility that their lives were not over.

The faculty could have taught at any first-rate college or university, and in fact, many of them did. They ranged in age and experience from university deans to young scholars. In addition to college professors, there were poets, city historians, artists, a well-known critic, and the former chairman of the fifty-six Yupik Eskimo villages. No one worked as a volunteer, for a university faculty is not best made of volunteers; the faculty were paid at the rate of adjunct professors at the best universities, for that was the level of effort and knowledge expected of them.

It was the fifth year of the course in the United States, the third year in Canada, the second year in the Yucatn, and work was underway at the Universidad Iberoamericana, the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and the Instituto Technologico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey to begin courses in central Mexico. The course was taught in English, Spanish, Yucatecan Maya, Cupik Eskimo, and would soon be taught in Kiowa and Cherokee in association with the University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma.

Twenty-three students in New York City who had already completed the course were enrolled in a second-year Bridge Course (between the end of the Clemente Course and the start of college), taught by Stuart Levine, dean of Bard College. In San Antonio Sih6, Yucatn, they were reading Maya classical literature in Maya with Miguel Angel May May, whose stories and criticism were beginning to win a national reputation. In Seattle, Lyall Bush, who had come to the course from the Washington Humanities Council, had replaced the Logic section of the course with a broader view he preferred to call Critical Thinking. Martin Kempner, national director of the Bard College Clemente Course in the Humanities, kept in constant touch with his directors at a dozen sites, pushing the academic level up and the attrition rate down.

Although the course had expanded to seventeen sites from the original experiment on the Lower East Side of New York, its aims had remained the same: through the humanities to enable poor people to make the journey into the public world, the political life as Pericles had defined it, beginning with family, and going on to neighborhood, community, and state. To do this successfully required an entirely different view of poverty and poor people. The old ideas about the poor had been proved wrong, or if not wrong, at least not very useful in assisting people out of multigenerational poverty. In truth, the poor had often lifted themselves out of poverty, but other than immigration and such obvious factors as equal justice before the law, how they did it was not well known.