Zest Books, 2443 Fillmore Street, Suite 340, San Francisco, CA 94115 | www.zestbooks.net

Copyright 2015 Emily Lindin | All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. | Juvenile Nonfiction / Language Arts / General | ISBN: 978-1-942186-00-7 | Design: Adam Grano | Production: Jimmy Presler

Foreword

By Amanda Hess

A couple of years ago, I started noticing a curious refrain repeated again and again in stories about American teenagers. When two high school football players were convicted of sexually assaulting a girl in Steubenville, Ohio, the judge advised teenagers to be careful how you record things on the social media so prevalent today. When a group of Virginia high school boys gleefully spread naked pictures of their female classmates through an Instagram sexting ring, local cops warned the girls about the dangers of logging online. Social media is destroying our lives, one sixteen-year-old girl sighed to Vanity Fair in 2013. Girls as young as eleven were competing to look sexy online, then branding other girls sluts for doing the same. Were seeing depression, anxiety, feelings of isolation, a California youth counselor said of the young women she worked with. The culprits, she said, were Facebook, Instagram, and Ask.fm.

Something about this explanation didnt feel quite right to me. I had braved the middle school hallway at a time before texting. It was hellish then, too. Many of the teen terrors that were now being pinned on the Internetsexual assault, bullying, and the pursuit of the perfect bodyhad been fixtures of the analog girl world I had inhabited. Now that I was all grown up, it felt as if my fellow adults were suffering from a kind of collective cultural amnesia. Maybe we had all repressed our most disturbing middle school memories. Or maybe it was just comforting to blame new gadgets for problems that had been plaguing us for generations. Its easier to confiscate a girls iPhone than to cleanse society of sexism. And anyway, there had been no Twitter or Tumblr back when we were that age. Grown-ups had detailed records of what our teen lives had really been like.

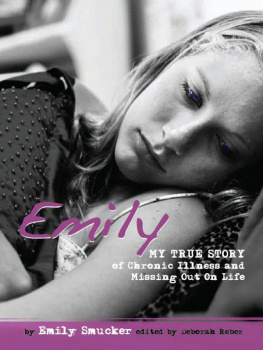

Then I found Emily Lindins blog. In 2013, twenty-seven-year-old Emily had dusted off her old middle school diary and started republishing the entries, verbatim and in chronological order, on a Tumblr called The UnSlut Project. Soon after, I discovered it and read it all in one sitting. In eleven-year-old Emilys world, Leonardo DiCaprio was the designated tween heartthrob. Limp Bizkit was the toast of Total Request Live. Tween boys gelled their hair into an inflexible shell that culminated in a ridge of spikes just above the forehead, and this was considered attractive. Hey: it was the late 90s. Except now, it was all online.

Clicking through Emilys Tumblr for the first time felt like exploiting a glitch in the space-time continuum. Here was a girl who chatted with friends on her Clueless-themed landline phone, slept in a bedroom plastered with Hanson posters, and could only access the Internet through a glacial dial-up modem that linked up to a free trial version of America Online. But her drama was thoroughly modern. Her sixth-grade boyfriend fed her whiskey and forced himself on her while his friend looked on. Her classmates decided that made her a bad girl. Unsourced rumors spread through notes and whispers. Boys told her to show them her boobs. Girls told her to kill herself. In her diary, Emily was nave, precocious, a little nerdy, and totally sexually inexperienced. At school, she was the class slut.

With each entry, Emily revealed another social antecedent for problems that we now like to think of as online issues. Before sexting, boys drew naked pictures of their female classmates on sheets of paper and passed them around. Before Facebook stalking, kids secretly eavesdropped on each other through three-way phone calls. Before texting, awkward middle schoolers enlisted friends to courier their love notes across the hall. Before cyberbullying, kids smiled in person then wheeled around and smeared each other with Machiavellian precision. Before Instagram, girls knew they were valued above all for the way they looked. Before Steubenville, boys figured out how to turn sexual assault into a team activity, goading one another into groping girls and directing one anothers unwanted advances.

Watching Emily and her peers fumble through adolescence at the dawn of the social web, its clear that our sexual bullying problem didnt originate online. The Internet just helped kick it to the next level. As soon as Emily logged onto AOL Instant Messenger for the first time, an anonymous user calling herself DieEmilyLindin casually messaged: Hi Emily. Why havent you killed yourself yet, you stupid slut? But before AIM, Emily had been advised to commit suicide via a handwritten note. And before we started calling this stuff the dark side of social media or the danger of the Internet, we called it drama, or dating, or just being a girl. In one entry, Emily watches The Basketball Diaries, a 1995 teen drama film starringwho else?Leonardo DiCaprio, and says of herself: I almost wish I had a screwed up life so I could be cool and record all of my thoughts. I feel so grateful to eleven-year-old Emily, who recorded all of her thoughts in her diary even though she couldnt recognize at the time just how screwed up her circumstances really were. And Im in awe of adult Emily, who now has the tenacity to revisit these most intimate and painful experiences, and the wisdom to show us a new way of using the Internetto fight back.

Introduction

By Emily Lindin

In April 2013, I read a news story about a seventeen-year-old girl named Rehtaeh Parsons from Halifax, Nova Scotia. She had been allegedly gang-raped by her classmates, who took photos of the attack and spread them around her school and community. She was targeted as a slut as a result, and suffered constant bullying in school and online. Over the next year and a half, she transferred schools multiple times to try to escape her reputation. Unable to cope with the emotional trauma, she began using drugs and alcohol. After a year and a half, she made the decision to end her own life.

As tragic and terrifying as it was, Rehtaehs wasnt the first story like this that Id heard. Girls throughout the United States and CanadaAmanda Todd, Audrie Pott, Phoebe Prince, Felicia Garcia, to name a few of the manyhave made the decision to commit suicide after relentless sexual bullying. Sometimes they are targeted after being the victim of sexual assault at the hands of their classmates. Sometimes the bullying follows their decision to engage in consensual sexual activity. Sometimes its because of the way they dress. Sometimes its because they developed breasts earlier than other girls. And sometimes, its for absolutely no discernible reason at allnot that theres ever a justifiable reason for sexual bullying.

Sexual bullying doesnt always result in suicide. But it is a particularly devastating type of bullying for a young girl to endure regardless of how she reacts to it. Thats because unlike victims of most other types of bullying, victims of sexual bullying usually cant turn to the adults in their life for support. A girl might fear that her parents, teachers, or community leaders will worsen the situation by accusing her of bringing the bullying upon herself by asking for it through her dress or behavior. And in many cases, her fears will be well-founded. The idea that girls are to blame for the abuse they receive is prevalent in the United States and Canadaand in many other countries we like to think of as relatively progressive when it comes to female sexuality and issues of womens equalityand it is cause for international concern. On an individual scale among teenagers and preteens, I refer to it as sexual bullying. On a larger, societal scale, the term slut shaming has become commonplace over the last few years. Ideas about what constitutes slut shaming vary: I define it as the implication that a girl or woman should feel inferior or guilty because of her sexual behaviorwhether real or perceived.