THE QUEENS OF

HASTINAPUR

SHARATH KOMARRAJU

For Sarayu

This book will probably be out of print by the time

youre old enough to read it. But what the hell.

Contents

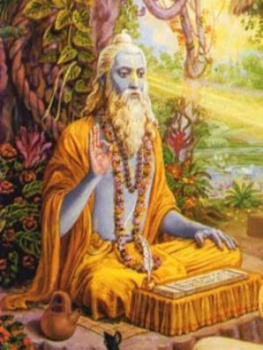

T he bare White Rock against which I sit, which rises up to touch the clouds, breathes a chilling current of air down my back. My hooded black cloak once all that I needed to protect me from the elements is now damp, its coarse cotton giving way at the seams under the arms. A gust of wind runs up the mountain, turns Yudhisthirs lifeless body a darker shade of blue, and nibbles at my shrivelled white hair.

I have been speaking for long, now, yet the tale of the great war is but at its very beginning. My body withers with each passing moment, and soon I shall lie down next to Hastinapurs High King and shut my eyes. But before that, I must make certain that the entire song passes my lips, for if the light once departs my body, the story of the Meru people and the battle of Kurukshetra shall forever remain untold.

Sometimes I wonder if anyone hears me here, for I see no bird or bee or flower or tree just the falling snow and the endless grey of the overhead skies. Perhaps all that I say here is in vain; perhaps my voice speaks just to the lifeless crags among which the Pandavas lie dead; perhaps even if I were to trick death long enough to narrate my tale, it shall never be uncovered.

If that is so, perhaps it is best that I lie down right now, and surrender to the weight of my eyelids

I lean forward on my seat to feel Yudhisthirs battle-hardened palm; even after all those years of peace, his hands bear the marks of war. With the sleeve of my cloak I clean the sleet off his hand, and to my utter surprise I sense his fingers tremble slightly, and then they wrap as one around mine. I watch the rest of his body for other signs of life, but there are none. His lips had already blackened, as though they had been dipped in the venom of hell. His eyelashes are freckled with ice.

But his trembling touch has given me my answer. Even if my listeners are lifeless rocks, I must go on. Even if my words are destined to lay forever buried under carpets of snow, I must go on. Even if they freeze in this air for a while, I must believe there will come a time in the far future, perhaps when summer arrives and melts them into life once again. Even when I see no hope, I must find some, deep within me.

So I hold on to Yudhisthirs hand and will myself to resume.

The hands of man yearn to grasp. His fingertips are born with the innate knowledge that they must curl around whatever they touch. To sate his hunger he kneads the nipples of his mother. As he begins to move about on all fours, he reaches for objects that catch his eye; he touches, he feels, and those that he likes, he clutches to his bosom. When he learns to walk, he holds the hand of his elder for support; when he is old enough to love, he sends out his fingers again, eager, groping, into the dark in desperate hope. He makes food for himself by guiding the path of the plough, and he makes the plough itself by felling trees with an axe, whose blade he forges from black iron extracted from the Earths breast all by means of his hands.

The mind of man yearns to grasp. Deep within it is a well of unslaked thirst that drives him forever on, asking questions of the Goddess, digging her for secrets, and when the Goddess answers each of his queries with a thousand of her own, he soldiers relentlessly on. He picks up each one of the puzzles at once, turning it over in his head, certain that he shall one day unravel them all.

The mind of man is also besotted with lust for power, for wealth, for status. Its tendrils are akin to those of a ravenous spider spinning an infinite web. There is never a moment when it is still. It is always teetering on the edge that separates instinct from thought, clawing, feeling

The soul of man yearns to grasp. From the time he gains consciousness, he is aware of two worlds that he at once inhabits: one outer world that seems to run of its own volition, oblivious to his whims and thoughts; and one inner world where he reigns supreme, where his word is decree, where there are no arguments to face, no wars to fight, where there is peace at every corner, where love and forgiveness bloom on every tree. But this inner world is locked in eternal combat with the outer, and his soul longs to shape the latter in the image of the former.

This yearning is the reason for all of mans most towering achievements. Without it, would we ever have rubbed together two stones on a cold winters night? Would we have written the book of mysteries? Would we have told each other tales of wars and triumphs and defeats, taught our children to be good, fed the old and weak, respected the dead? Would we have made love, passed on our memories, kindled this flame of hope in our hearts?

And yet it is this same yearning that brings out the worst in man. The same hand that guides the plough also grabs at the hilt of a sword. The same mind that lusts for knowledge and wisdom also yearns for revenge, for power over another. The same soul that acknowledges the free existence of the outside world seeks to bend it by waging wars, by placing curses, by enslaving kingdoms.

The journey of a priestess is not to escape this desire to grasp and to mould indeed, none of us can but to realize its futility. The march of creation is inexorable. The sweep of time extends thousands of years into the past and into the future. The life of one man and the life of one race is but a blink of the Goddesss eye. An age is but one heave of the Goddesss chest. All of the thoughts that have occurred in all human minds through the epochs are contained within the Goddesss one heartbeat.

This notion, then, that we control the course of history is but an illusion. I told the Wise Ones on the mountain this on the day Pritha and Gandhari were betrothed in Hastinapur that we must stay away from Earth from now, allow the Goddess to exert her will in her own patient, invisible manner and they nodded.

Yes, they said. The Lady of the River speaks well. We have meddled enough in Earths affairs. Let us now turn our gaze inward, and bow to the will of the Goddess.

But it is the great folly of men even the wisest of them that they think they know the Goddesss will. They can see into her mind, these men claim, forgetting that her mind holds the entire known universe within it. They have spoken to the Goddess, they insist, forgetting that she has no mouth with which to speak or scream. Perhaps this is why she has so many who speak on her behalf these men who are but mere mites of dust by her feet. They can claim to know her because she is unknowable. They see her form because she is formless. They speak her words because she never does.

And so it is with Merus Wise Ones. Not so much as a moon had passed after the weddings in Hastinapur when I went one morning to the Crystal Lake to pay my respects. It was a morning like every other until it was not.

T he high metal gates opened. Ganga walked out through them into the garden, acknowledging the bowing guards with a swift nod. Her black cloak was draped around her shoulders, her hair thrown open to the morning air. If there was one thing she loved about summers, it was the dawn breeze that came running up the slopes from the east, leaving in its wake a trail of white roses in full bloom.

Even in the controlled environs of Meru there was summer, winter, autumn and spring. The hot months did not make you sweat as they did on Earth, and the cold ones did not make you shiver quite as much, but one could still tell one season from another. The Elementals strove to keep everyone on the mountain in comfort through the year, but hardly a day went by without Ganga hearing someone or the other complaining that it was either too hot or too cold.

Next page