Comics Art in China

Comics Art in China

John A. Lent and Xu Ying

University Press of Mississippi / Jackson

The color reproductions in this book are funded by a generous donation from the Huang Yao Foundation and Carolyn Wong.

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2017 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in Canada

First printing 2017

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lent, John A., author. | Xu, Ying, 1959 author.

Title: Comics art in China / John A. Lent and Xu Ying.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017003509 (print) | LCCN 2017007881 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496811745 (hardback) | ISBN 9781496811752 (epub single) | ISBN 9781496811769 (epub institutional) | ISBN 9781496811776 (pdf single) | ISBN 9781496811783 (pdf institutional)

Subjects: LCSH: Caricatures and cartoonsChinaHistory. | Animated filmsChinaHistory and criticism. | Arts and societyChinaHistory. | BISAC: LITERARY CRITICISM / Comics & Graphic Novels. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Popular Culture. | HISTORY / Asia / China.

Classification: LCC NC1690 .L46 2017 (print) | LCC NC1690 (ebook) | DDC 741.5/6951dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017003509

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

To my many cartoonist friends

worldwide and the research community

that studies them: you have made

it a magnificent adventure

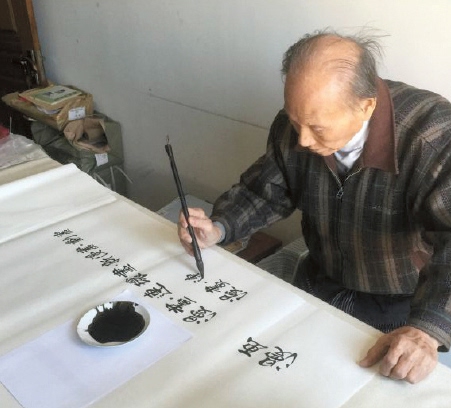

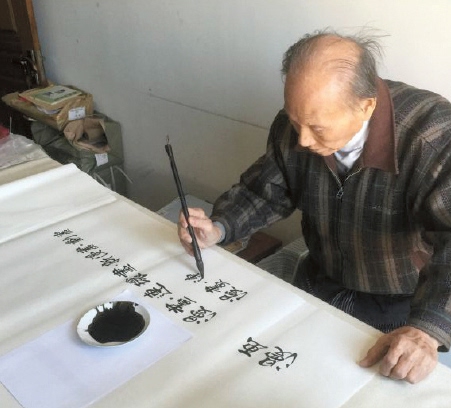

Fang Cheng at work

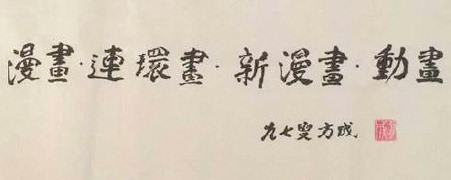

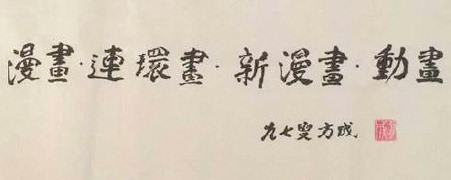

Manhua, lianhuanhua, xinmanhua, and donghua

Cartoons, picture books, comics, and animation

Calligraphy by Fang Cheng, 2016, age ninety-seven

Contents

Preface

Every book has a history of its own.

This one originated in the late 1980s when I met archaeologist and professor Alfonz Lengyel and his wife, HongYing Liu-Lengyel. Soon after, HongYing enrolled as a PhD student under my supervision at Temple University. For her dissertation, HongYing and I fashioned a survey of Chinas cartoonists, certainly a new topic in academia at that time. Before embarking on her fieldwork, I instructed her to interview as many cartoonists as possible, starting with the oldest. She took my advice seriously, even interviewing Zhang Leping in his hospital bed shortly before he died. HongYing and Alfonz talked to about 100 cartoonists, quite a feat at a time when networking was not as facile as later in the internet era.

HongYing was the first of a number of doctoral candidates, who under my direction, researched cartoons, comics, and animation in South Korea (two), Taiwan (two), Japan, India, Turkey, Cuba, and Kenya. Others who studied comic art with me for purposes other than the completion of PhD dissertations wrote about Nepal, Bangladesh, Thailand, Peru, South Korea, Taiwan, and China.

In 1993, during the second of at least thirty trips to China, I began interviewing cartoonists and animators in Shanghai. With much help from HongYing, Alfonz, and cartoonist/animator Zhan Tong, I got a feel for the Shanghai cartooning scene, which was intensified and expanded to all of China after I met Xu Ying in 1996. During the past fifteen years, Ying and I, either together or solely, interviewed at least 121 comic art-related personnel in many cities of China. Some were interviewed multiple times (see Appendix).

Thus, interviewing was a major research technique used for this book. In most cases, loosely structured interview schedules were used, allowing the artists and managers leeway in how they responded to questions and at what length. Interviews were done wherever the interviewees chose: their homes, restaurants, my hotel room, their offices or studios. Some were conducted at festivals, conferences, universities, and museums where either one of us or both were invited to speak.

Because almost all interviews were with mainland cartoonists and animators, the overall tenor of the discourse leans to that of the Peoples Republic of China and the Communist Party. The senior author interviewed cartoonists and animators in Taiwan and Hong Kong on several occasions, but dwelt primarily on contemporary, not historical, issues during those discussions. Whenever possible, the Guomindang perspective is given, accessed from the many interviews conducted with senior Taiwanese political cartoonists by Hsiao Hsiang-wen, whose doctoral dissertation I supervised, and from secondary sources. Although we do not apologize for our heavy reliance on the interviews (to the contrary, we consider the interviews with the giants of mainland cartooning to be a major strength of this book), we do recognize that interviews have pitfalls and do not tell the whole story. We attempt to account for that issue by critically appraising what we were told by interviewees, and, in some instances, offering alternative perspectives.

Observation was also a useful research technique, allowing us to see where artists worked (studios, offices, and homes) and to view their works (in private collections, exhibitions, and museums). We were invited guests to museums dedicated to individual cartoonists Bi Keguan, Ding Cong, Feng Zikai, and Liao Bingxiong, as well as to the Frog Cartoon Groups galleries housing works by Hua Junwu and Ying Tao. We gathered information at Shanghai University, Communication University of China, Nanjing University of Finance and Economics, and Jilin College of the Arts Animation School, where I hold visiting professorships.

As already stated, both of us were involved in most interviews, which Xu Ying interpreted; she was also responsible for finding and translating Chinese-language resources, and for verifying facts and names in the final manuscript. I was responsible for researching/reading English-language books, articles, and internet postings, for locating non-English-language sources, for analysis of the gathered information, and for all of the writing, editing, and preparation of the manuscript.

In these pages, comic art is an all-encompassing term. More specifically, cartoons normally refer to political and social commentary drawings; comic strips are sole or multiple panels used in newspapers to tell a humorous episode or continue a serialized story; comic books and xinmanhua are periodicals with a number of stories that can be serialized or completed in one issue; lianhuanhua are palm-size books that usually tell one story with one image per page; animation consists of filmed cartoons using movement and sound; and caricature means a likeness of an individual that is highly exaggerated.

As already implied, the study is primarily confined to mainland China and does not, in any measurable sense, include Hong Kong, Taiwan, or diasporic Chinese communities scattered around the world. Occasional references to Hong Kong and Taiwan are unavoidably included, because both have served as havens during times of crises, such as in World War II, the China Civil War, and the 1949 overthrow of the Guomindang Party; some of the early Chinese cartoons started in Hong Kong and moved to the mainland, and vice versa, and Hong Kong often served as mainland Chinas bridge to the West.

Names are given in Pinyin (Mao Zedong, Guomindang, etc.). Birth and death dates are provided for most individuals discussed, but there were instances where we could not determine these dates.

Next page