Table of Contents

For Brian Bedford

Foreword

By John Simon

Literary trends come and go, and yesterdays favorite may be forgotten tomorrow. But most nations have one supreme authorpoet, playwright or novelistwho is the fountainhead of their literature. For England, it is Shakespeare; for Germany, Goethe; for Italy, Dante.

For France, this role is shared by two superstars: the great tragedian Racine, and the great comedian Molire. Racine stands for purity, a classically restrained vocabulary of great musicality; Molire, whose motto was, I gather my property where I find it, offers profusion of motley mirth.

Most of Molires greatest dramatic achievements are in rhymed verse, in the traditional French alexandrine, a rhymed, regular, twelve-syllable line. English verse drama, unlike French, is in an accented language and traditionally espouses the five-beat pentameter line of slightly varied length. It avoids being as regimented as the unaccentual French, lest the monotonously placed drumbeats produce doggerel. The wonder of it is that Wilburs translations attain all the lightly tripping elegance of the originals.

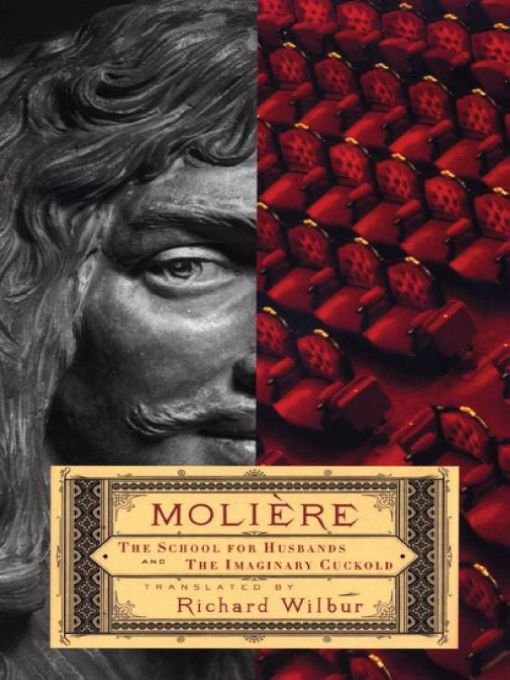

It should be noted that Wilbur is one of our finest poets, but also one of the bestperhaps the bestverse translators into English. As a poet, he has won all possible prizes, but he deserves as many as translator, not only of the verse plays of Molire and Racine, but also of lyrics from various languages. The translations contained in this volumeThe School for Husbands and The Imaginary Cuckold, or Sganarelleshould provide ample proof.

Consider, for example, Wilbur s masterly use of enjambmentrun-on lines taboo in the strictly end-stopped Frenchto excellent effect. Take this enjambed couplet, My names no longer Sganarelle, and folk /Will dub me Mister Staghorn, for a joke. The enjambment both slightly downplays the rhyme and creates a certain suspense: Just what will folk do? It has been argued, that there is some loss of darkness in the translations, to which Wilbur replies, in his collection of prose pieces The Catbirds Song, English rhyming is more emphatic than French rhyming, so that a translation into English couplets will more often have the whip-crack sound of joke or epigram than the original did.

That is a consequence of an accentual language, but, in my view, neither decreases nor increases whatever is meant by darkness. What is true and important about the couplets in both French and English is that they add musicality while also acting as a mnemonic aid by making consecutive lines click satisfyingly and memorably into place. They also challenge the actor to the bravura feat of neither emphasizing nor wholly losing the rhymeor, otherwise put, to reconcile naturalness and artifice.

There exists a centuries-old toy the French call bilboquet and we call cup and ball. A wooden ball is attached by a fairly extensive string to a long-handled wooden cup; when the ball is propelled into the air, it must be caught by the cup into which it snugly fits. So, too, Wilbur s couplets, in which there are no awkward inversions, omissions, flab or obscurities.You might say they snap to.

Some examples from Cuckold. Sganarelles wife, of her husband: He saves his hugs for other women, the swine, / And feeds their appetites while starving mine. And he, jealously, to her: Why, when your mates well favored, spry and dapper, / Were you attracted to this whippersnapper? The maid, to her mistress, Clie, as they look at the locket picture of her would-be lover, Llie: He has a faithful lover s face, thats true, / And youre quite right to love him as you do.

Note the monosyllabic, so-called masculine swine-mine rhyme, and the feminine dapper-whippersnapper rhyme handled with equal easefulness, with the utterance perfectly fitted to the characters and situationseveryday language suited to bourgeois speakers and their savvy servants. How aptly the rhymes fall where they dolike the ball into the bilboquetallowing you to subliminally sense the rhyming without dwelling on it consciously, and so impede the smooth flow of the dialogue.

Now let us take stock of Molires artful construction of the farce in Cuckold, while noting how that entire play, like much of Husbands, revolves around cuckoldry, whether real or imagined. Cuckoldry is a principal topic of the Italian commedia dellarte, the traditional clown shows that so much of contemporaneous French farce and early Molire imitated.

Why, we may ask, is this subject all over romance-language theater, whereas, of all Shakespeares plays, featured only in Othello and less prominently in Cymbeline and The Winters Tale? Because in Latin countries, at least in prefeminist times, though a husband was allowed a mistress, absolute faithfulness of the wife was a must. Consequently, the metaphoric horns of the husband, real or merely suspected, become a prime subject of both comedy and tragedy, whether as laughing matter or as cause of bloodshed.

A farce such as Cuckold depends entirely on plot and language: The characters are as stock as can be: The typical older, bamboozled husband; the typical young lover and married or unmarriedbut closely guarded or promised to anotherbeloved; the typical blustering and draconian father; the typical cunning or rascally servants; and, of course, misunderstandings galore on the way to a glibly contrived happy ending.

But look how especially intricate the imbroglio is in Cuckold, thanks to nothing much more than Clies locket found by the wife of the jealous Sganarelle, a little courtesy of his to the fainting Clie, and the wifes Samaritan kindness to the crushed Llie, who mistakenly assumes Clie to have married Sganarelle. There is a kind of geometry to this that a mathematician could diagram, and it takes a maids arbitrary common sense and a potential rivals clandestine previous marriage for the facile disentangling of knots.

What delights is the way one misapprehension dovetails into another, and also the vengeance-bent Sganarelles cowardly tergiversations couched in soliloquy worthy of some tragic hero. Further, the comical quarrels between Sganarelle and wife, and between Llie and Clie, whose very rhyming names contribute to the comic absurdity.

There is, clearly, no allowance for the characters to have a certain density beyond serving as instruments of the plot. In The School for Husbands some greater individualization appears, though still a long way short of that in the later masterpieces.

Between this 1660 farce and the 1661 comedy, the difference does not affect plot. The story is still arrantly contrived. A dying man bequeathed his little daughters to a pair of brothers, his friends, for rearing and, presumably, eventual marrying. Lonor was given to Ariste, now sixtyish; Isabelle to Sganarelle, now forty. Isabelle, kept on a leash by despotic Sganarelle, has fallen in love with young Valre, who has been trailing her and has elicited an exchange of amorous glances. Lonor, whom the wise Ariste brought up tolerantly, is devoted to him. There is thus a sense of how a liberal character begets affection, while a domineering one elicits rebellion.