ANTHONY

STRADIVARI

THE C ELEBRATED V IOLIN M AKER

P RECEDED BY THE O RIGIN AND T RANSFORMATION OF B OW I NSTRUMENTS AND F OLLOWED BY A T HEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF THE B OW

F RANOIS -J OSEPH F TIS

N EW I NTRODUCTION BY S TEWART P OLLENS

D OVER P UBLICATIONS , I NC .

M INEOLA , N EW Y ORK

Copyright

Introduction copyright 2013 by Stewart Pollens.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2013, is an unabridged republication of Notice of Anthony Stradivari, the Celebrated Violin-Maker, originally published by Robert Cocks and Co., London, in 1864. Stewart Pollens has prepared a new Introduction for this Dover edition.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-49826-3

ISBN-10: 0-486-49826-3

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

49826301

www.doverpublications.com

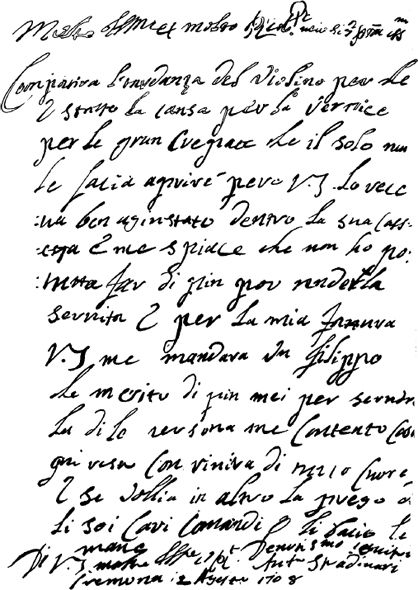

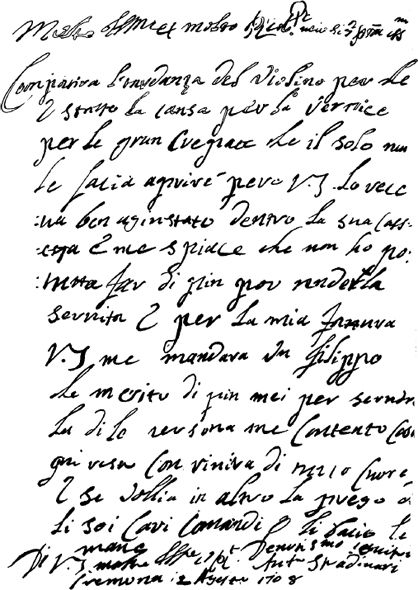

EAC SIMILE OF A LETTER WRITTEN BY ANTHONY STRADIVARI.

_____________________________________________

TO

CHARLES H. C. PLOWDEN, ESQ. F.S.A. F.R.G.S.

AN ARDENT ADMIRER AND COLLECTOR

OF

OLD CREMONESE INSTRUMENTS,

THIS TRANSLATION

IS DEDICATED

BY

THE EDITOR.

INTRODUCTION TO THE DOVER EDITION

F RANOIS -Joseph Ftis, the author of Anthony Stradivari, the Celebrated Violin Maker, was born in Lige, Belgium in 1784 and died in Brussels in 1871. He began his musical education with his father, Antoine, who was a church organist, violinist, and conductor, and from him Franois-Joseph learned to play the organ, piano, and violin. At the age of nine he wrote a violin concerto, and by the time he entered the Paris Conservatory in the year 1800 he had composed two piano concertos and three string quartets. At the Paris Conservatory he studied theory and music history, and won a second prize in composition in 1807. He married in 1806 and left Paris with his wife in 1811, settling first in Bouvignes and later Douai, where he taught and worked as a church organist. In 1818 he returned to Paris where he continued teaching and composing (his works include seven comic and dramatic operas, a sacred mass and secular cantata, chamber music, and solo works for piano and organ). In 1821 he received a teaching appointment at the Paris Conservatory and also worked as its librarian from 1826 through 1830. In 1827 Ftis founded the musicological journal Revue musicale.

In 1833 he returned to his native Belgium to become the director of the Brussels Conservatory. In addition to his administrative duties, he continued to contribute articles and reviews to newspapers and musical journals, and he wrote numerous methods, treatises, and manuals devoted to harmony, counterpoint, solfge, accompaniment, and composition. Perhaps his most ambitious undertaking was his Biographie universelle des musiciens et bibliographie gnrale de la musique, a multi-volume work published between 1835 and 1844. This comprehensive musical encyclopedia went through numerous editions; the last, published in 18781880, was reprinted as recently as 1963. Though Ftis Biographie universelle has come under criticism for factual errors, it remains an invaluable reference work, particularly with regard to events he witnessed and historical figures he knew personally.

Several of Ftis articles in his Biographie universelle were later adapted for republication as monographs. This monograph on Stradivari was first published in Paris in 1856 by the noted violin maker and dealer Jean Baptiste Vuillaume under the title Antoine Stradivari luthier clbre connu sous le nom de Stradivarius, prcd de recherches historiques et critiques sur lorigine et les transformations des instruments a archet et suivi danalyses thoriques sur larchet et sur Franois Tourte auteur de ses derniers perfectionnements. This Dover edition is a reprint of the English edition published in London by Robert Cocks and Co. in 1864. In addition to the monograph devoted to Stradivari, it includes essays on the origin of bowed instruments, the schools of violin making, the Guarneri family, Franois-Xavier Tourte, and a technical study of his bows.

Ftis monograph on Stradivari was translated and edited by John Bishop with the permission of the author. Both Ftis and Bishop acknowledge the technical assistance provided by the violin maker Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume (17981875), who began his career in Mirecourt (a French town in the Vosges region largely devoted to violin making) under the tutelage of his father, Claude Franois. In 1818 Jean-Baptiste moved to Paris to work for the violin maker Franois Chanot and later for Nicolas-Antoine Lt. In 1825 he set up his own establishment at 46 rue Croix-des-Petits-Champs behind the Louvre and came to dominate the violin trade in the mid-nineteenth century, both as a craftsman and dealer. Vuillaume became one of Frances finest violin makers and focused his attention on copying the work of Antonio Stradivari and Giuseppe Guarneri del Ges. He was said to have had an excellent eye for old instruments, and with his professional interest in the construction of violins and bows, he was clearly the ideal consultant for Ftis.

Ftis begins this work with an essay Historical Researches on the Origin and Transformations of Bow-Instruments. In this essay, he reconsiders an earlier theory (presented in his Sketch on the History of the Violin that appeared in an earlier monograph on Paganini) that the use of a bow with a stringed instrument was an invention of the West, suggesting instead that the Sri Lankan ravanastron was the earliest form of bowed instrument, and that it had been invented some five-thousand years before the Christian Era. Most modern historians, however, dispute this and trace bowing back to tenth-century central Asia. Ftis goes on to describe various European precursors of the violin dating from the sixth through the eleventh centuries, such as the crouth, rotta, rebec, and vielle, citing textual and iconographic sources and including copious bibliographic references.

Regarding the development of the violin, Ftis drew upon Martin Agricolas Musica instrumentalis deudsch (1529), Giovanni Maria Lanfrancos Scintille di Musica (1533), Sylvestro Ganassis Regola Rubertina (1542), Scipione Cerretos Della prattica musica (1601), Michael Praetoriuss Syntagma musica (1619), and Marin Mersennes Harmonie universelle (1636), which remain the principal sources for reconstructing the early history of the violin. (Readers are advised to consult the originals or facsimiles to verify technical detailsfor example Ftis inaccurately transcribes the tunings of a quartet of viols described in Agricolas Musica instrumentalis deudsch. )

Regarding the earliest known violin, Ftis cites Jean-Benjamin de La Bordes Essay sur la Musique (Paris, 1780), which describes a four-string violin labeled Joann. Kerlino, ann. 1449. Ftis remarks that this instrument found its way to Paris and in 1804 came into the hands of the violin maker Jean Gabriel Koliker (active in Paris, 17831820). Today, Kerlino is believed to have been a fictional character and the instrument in question either a fabrication by Koliker or perhaps a conversion from an earlier form, such as a viol or lira. The next maker Ftis mentions is Pietro Dardelli of Mantua, and though no violins of his are known today, this Franciscan friar is believed to have made lutes. Ftis then touches upon the work of the Gaspard Duiffoprugcar (also spelled Tieffenbrucker), Ventura Linarolo, Peregrino Zanetto, and one Morglato Morella of Mantua, who supposedly worked in Venice after 1550. Though there is evidence that the first three makers existed, Morglato Morella is apparently another fictional figure whose name has been copied from one biographical dictionary to the next.

Next page