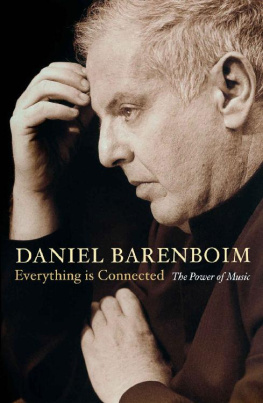

Daniel Barenboim was born in Buenos Aires in 1942, and in 1952 moved with his family to Israel. He made his piano dbut at the age of seven and has since played with and conducted every major orchestra in the world. He was Music Director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1991 to 2006 and General Music Director of the Berlin State Opera from 1992, he appears regularly with the Berlin Philharmonic and Vienna Philharmonic orchestras, and in 2006 he was named Maestro Scaligero at La Scala, Milan.

He has been honoured around the world for his work in promoting peace in the Middle East. In 1999, together with the Palestinian literary scholar Edward Said he founded the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, which brings together young musicians from Israel and the Arab countries, seeking to enable dialogue between the various cultures of the Middle East. In 2007 he was named UN messenger of peace and was also awarded the Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medal, one of the most prestigious honours in classical music. He became the first performer chosen to deliver the BBC Reith Lectures in 2006, and gave a six-part lecture series at Harvard University as Charles Eliot Norton Professor. He is the author of three books: his autobiography A Life in Music, Parallels and Paradoxes, written with Edward Said, and Dialoghi su Musica e Theatro. Tristano e Isotta, co-authored with Patrice Chreau and published in Italy in 2008.

He lives in Berlin and holds citizenship in Argentina, Israel, Spain and Palestine.

www.danielbarenboim.com

To the musicians of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra

CONTENTS

The beginning of a concert is more privileged than the beginning of a book. One could say that sound itself is more privileged than words. A book is full of the same words that are used every day, day after day, to explain, describe, demand, argue, beg, enthuse, tell the truth and lie. Our thoughts take shape in words; therefore, the words on the page must compete with the words in our minds. Music has a much larger world of associations at its disposal precisely because of its ambivalent nature; it is both inside and outside the world.

In todays world, music has a cacophonous omnipresence in restaurants, aeroplanes and the like, but it is precisely this omnipresence that represents the greatest hindrance to the integration of music into our society. No school would eliminate the study of language, mathematics, or history from its curriculum, yet the study of music, which encompasses so many aspects of these fields and can even contribute to a better understanding of them, is often entirely ignored.

This is not a book for musicians, nor is it one for nonmusicians, but rather for the curious mind that wishes to discover the parallels between music and life and the wisdom that becomes audible to the thinking ear. This is not a privilege reserved for highly talented musicians who receive musical training from a very early age, nor is it an ivory tower, an exclusive luxury for the wealthy; I would contend that it is a basic necessity to develop the intelligence of the ear. As I will explain in the chapter Listening and Hearing, we can learn a great deal for life from the structures, principles and laws inherent in music, whether these are experienced by the listener or the performer.

Many of the topics I discuss in this book are ones that have occupied my thoughts for decades, and are the result of nearly sixty years of performance, instruction and contemplation. In my first book, A Life in Music, which has an autobiographical thread without being an autobiography, I began to touch on these subjects. In the book I wrote with Edward Said, Parallels and Paradoxes, we explored the relationships between music and society. When I was invited to deliver the Norton lectures at Harvard University in the autumn of 2006, I naturally seized the opportunity to develop my ideas on the connections between music and life more extensively, and this book is a further development of these thoughts.

I firmly believe that it is impossible to speak about music. There have been many definitions of music which have, in fact, merely described a subjective reaction to it. The only really precise and objective definition for me is by Ferruccio Busoni, the great Italian pianist and composer, who said that music is sonorous air. It says everything and nothing at the same time. Schopenhauer, on the other hand, saw in music an idea of the world. In music, as in life, it is really only possible to speak about our own reactions and perceptions. If I attempt to speak about music, it is because the impossible has always attracted me more than the difficult. If there is some sense behind it, to attempt the impossible is, by definition, an adventure and gives me a feeling of activity, which I find highly attractive. It has the added advantage that failure is not only tolerated but expected. I will therefore attempt the impossible and try to draw some connections between the inexpressible content of music and the inexpressible content of life.

Isnt music, after all, just a collection of beautiful sounds? John Locke wrote in his in many ways very forward-looking treatise, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, published in 1692, that Musick is thought to

Let us first look at the physical phenomenon that allows us to experience a piece of music, which is sound. Here we encounter one of the great difficulties in defining music: music expresses itself through sound, but sound in itself is not yet music it is merely the means by which the message of music or its content is transmitted. When describing sound, very often we speak in terms of colour: a bright sound or a dark sound. This is very subjective; what is dark for one is light for the other and vice versa. There are other elements of sound, however, which are not subjective. Sound is a physical reality that can and should be observed objectively. When doing so, we notice that it disappears as it stops; it is ephemeral. It is not an object, such as a chair, which you can leave in an empty room and return later to find it still there, just as you left it. Sound does not remain in this world; it evaporates into silence.

Sound is not independent it does not exist by itself, but has a permanent, constant and unavoidable relationship to silence. In this context the first note is not the beginning it comes out of the silence that precedes it. If sound stands in relation to silence, what kind of relationship is it? Does sound dominate silence, or does silence dominate sound? After careful observation, we notice that the relationship between sound and silence is the equivalent of the relationship between a physical object and the force of gravity. An object that is lifted from the ground demands a certain amount of energy to keep it at the height to which it has been raised. Unless one provides additional energy, the object will fall to the ground, obeying the laws of gravity. In much the same way, unless sound is sustained, it is driven to silence. The musician who produces a sound literally brings it into the physical world. Furthermore, unless he provides added energy, the sound will die. This is the lifespan of a single note it is finite. The terminology is plain: the note dies. And here we might have the first clear indication of content in music: the disappearance of sound by its transformation into silence is the definition of its being limited in time.

Some instruments, particularly percussion instruments, including the piano, produce sounds that we refer to as having a real-life duration; in other words, after the sound is produced, it immediately begins to decay. With others, such as stringed instruments, there are ways to sustain the sound longer than that of a percussion instrument: for example, by changing the direction of the bow and making the change smooth enough so that it becomes inaudible. Sustaining the sound is in any case an act of defiance against the pull of silence, which attempts to limit the length of the sound.