BY THE SAME AUTHOR

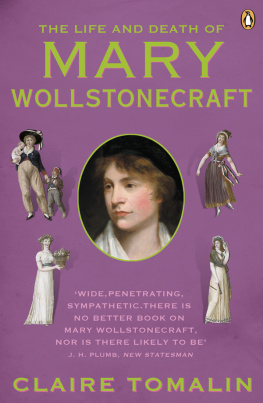

The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft

Shelley and His World

Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life

The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens

The Winter Wife (play)

Mrs Jordans Profession

Jane Austen: A Life

Several Strangers: Writing from Three Decades

Samuel Pepys: The Unequalled Self

Thomas Hardy: The Time-Torn Man

Charles Dickens: A Life

Poems of Thomas Hardy (selected and introduced)

Poems of John Keats (selected and introduced)

Poems of John Milton (selected and introduced)

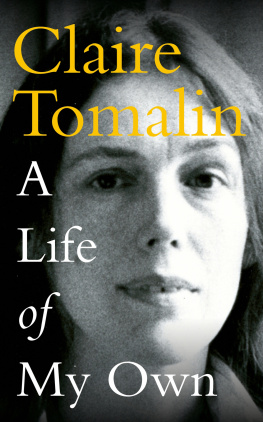

Claire Tomalin

A LIFE OF MY OWN

VIKING

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Viking is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Viking 2017

Copyright Claire Tomalin, 2017

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Front cover photograph Frank Herrmann

Photograph copyright Frank Herrmann. All other photographs courtesy of the author.

ISBN: 978-0-241-97482-7

List of Illustrations

Introductory Note

Writing about myself has not been easy. I have tried to be as truthful as possible, which has meant moving between the trivial and the tragic in a way that could seem callous. But that is how life is. Even when you are at the worst moments and would like to give all your attention to grief, you still have to clean the house and pay the bills; you may even enjoy your lunch. One of my aims in writing was to insist on the seamlessness of life something I saw presented by Pepys in his diaries, in which he gives the texture of the days as he lived them, work and play mixed together, never pretending that he felt as he should, or behaved better than he did.

I set out to describe as best I could my experience of the world, how it was for a European girl growing up in mid-twentieth-century England, how I got my education, how I made friends and related to different families who were good to me, how I was carried along by conflicting desires to have children and a worthwhile working life; and how long it took me to get going with the work I most enjoy and value: researching and writing historical biographies.

In taking on this self-imposed task, I was driven partly by curiosity: what would I learn about myself? Through the process of examining my life, I thought I might understand myself better. One thing I have learnt is that, while I used to think I was making individual choices, now, looking back, I see clearly that I was following trends and general patterns of behaviour which I was about as powerless to resist as a migrating bird or a salmon swimming upstream. And I was driven to make progress in my career by my first husbands not infrequent decisions to abandon the family. For me the Sixties did not always swing cheerfully.

How reliable is memory? Mine brings many scenes from my childhood, scenes I can visualize clearly and in some cases hear, and I believe these to be true memories. They are hard to check, though, because neither of my parents was inclined to talk about those early years, and my sister and I were not close to one another as adults. My mother talked to me a great deal about aspects of her life before I was born but had little to say of the years of my childhood. My fathers long memoir has helped me write this book, as will be obvious, since it starts with an account of my parents ill-starred marriage. All three of them are now dead.

To my surprise I found after my fathers death that he had kept almost every letter I wrote to him from the age of eleven. So here was an aide-mmoire that gave me both the facts and the feelings that had gone with them, insofar as I had been prepared to tell him about them. I did not tell all, but I have been surprised to find how much I did reveal to him maybe because my letters were written as much to my stepmother, whom I liked, and whose opinion I valued. Almost none of my letters to my mother have survived. There was no doubt of my love for her or hers for me, but by my teens I had learnt to censor what I told her of my feelings, behaviour and ambitions.

My copious early diaries disappeared during the years I was moving between Paris and Cambridge. From 1960, when I was twenty-seven, I kept basic diaries, mostly giving little more than appointments although expanding into commentary, cheerful, sad or angry, from time to time. I was surprised to find how much they brought back to me. At various points in my life I also wrote private accounts of episodes I wanted to record for myself.

My children are of course at the heart of my life, but I decided to say the minimum about them, not wanting to intrude on them or attribute feelings or remarks to them. I have asked them for their memories and been helped by them, especially in writing about their father and our life in Gloucester Crescent. My son Tom figures more largely for this reason: I believe it is important for people to know what it is like to be a disabled child growing up, and what is involved in being the parent of such a child. These are common experiences but still little understood. Tom has now lived longer than his fathers lifespan and his courage always amazes me.

My story should be cheering to anyone who is finding it hard to establish a career they find congenial. I spent my girlhood convinced that poetry was my vocation I wrote hundreds of poems and was encouraged even at Cambridge to believe that I was a poet. But my poems always related more to literature than to life. I saw this as I left Cambridge and, although producing poems had given me the greatest pleasure I knew, I resolved to write no more. It left me rather stranded: what was I to do? With an English degree I found literary work, in publishing, mostly reading manuscripts, then in reviewing, occasional broadcasting and literary editing. Only in the early 1970s, as I approached forty, did I start working on my first historical biography, but I still had to earn my living by working as a literary editor. It was 1986 and I was in my mid-fifties before I could concentrate on full-time research and writing. I found great happiness in this work, and for the next twenty-five years I researched and wrote steadily. So at last I found my true vocation.

I am a Londoner, born here and settled here, and my first chapter is about how this came about. Both my parents had gifts which brought them to study in London, my father from the Alps of the Haute-Savoie, my mother from Liverpool in north-west England. London was the city of their dreams, and also where they met and married. The book begins with my father, still a schoolboy, arriving in London in 1921.

1

A London Romance