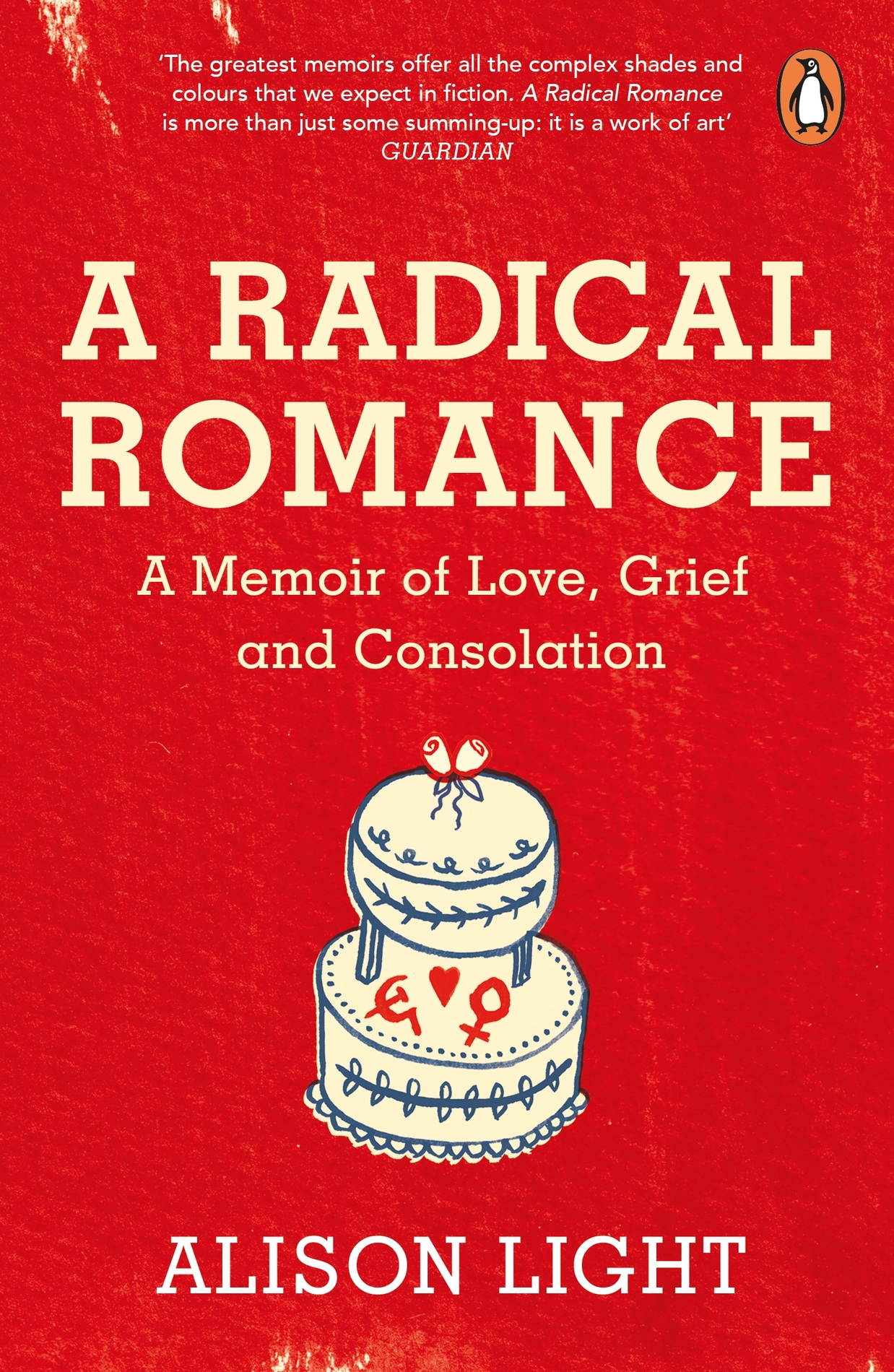

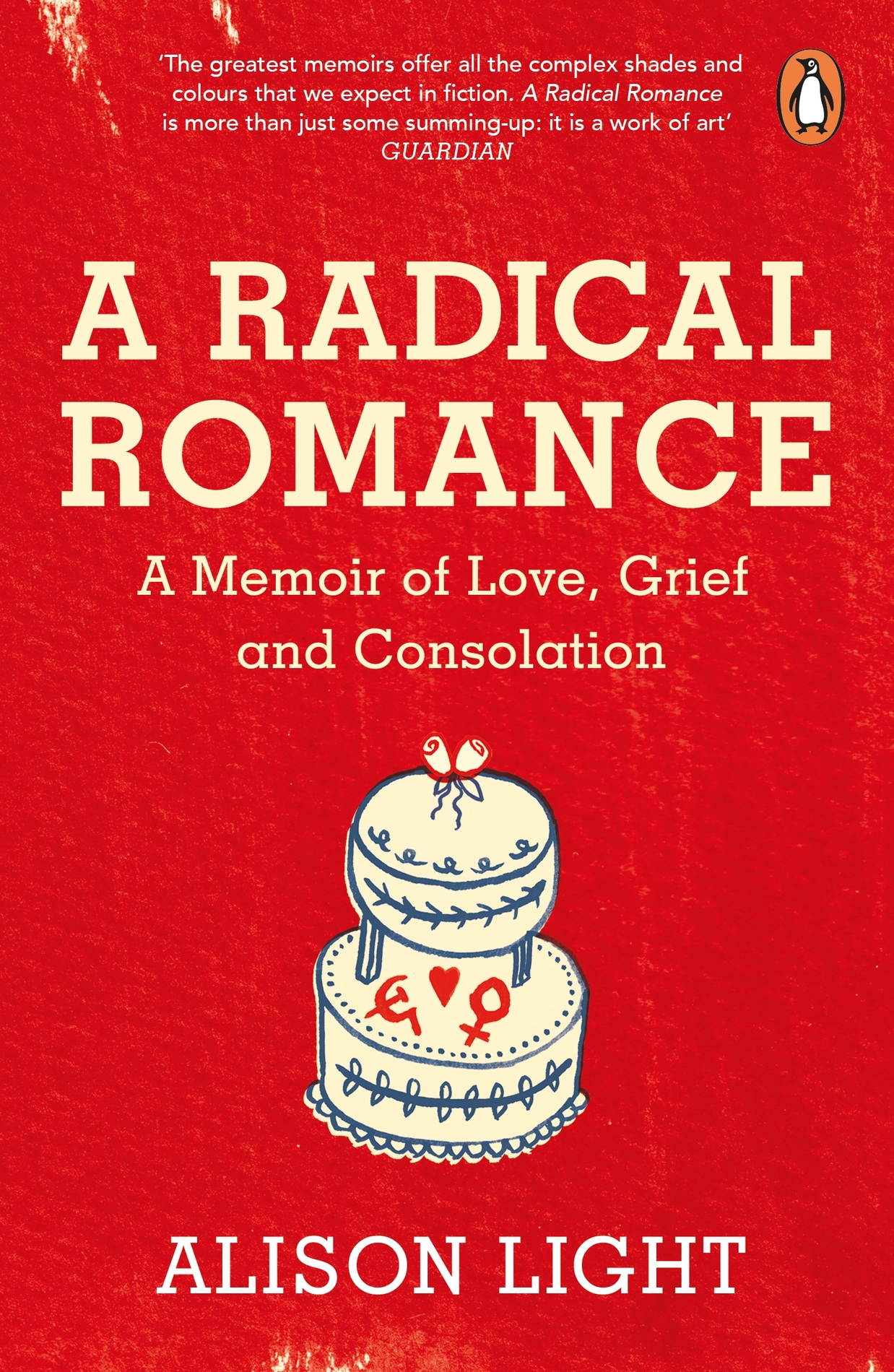

Alison Light

A Radical Romance

A Memoir of Love, Grief and Consolation

Contents

About the Author

Alison Light is a writer and critic. She is an honorary professor in the Department of English at University College, London, Honorary Professorial Fellow at Edinburgh University and a Senior Research Fellow at Pembroke College, Oxford. A regular contributor to the London Review of Books, she is the author of the much-acclaimed Mrs Woolf and the Servants and Common People, which was shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize. She lives in Oxford.

By the same author

Forever England: Femininity, Literature and Conservatism between the Wars

Mrs Woolf and the Servants

Common People: The History of an English Family

For John OHalloran

Preface: Love and History

In the summer of 1955, when I was born, Raphael fell in love. Or rather Ralph did. He had changed his name when recruiting for the St Pancras branch of the British Communist Party, because the London comrades said they couldnt pronounce it. He was twenty and Jean, his inamorata, was eighteen. Both came from Party families (the Communist Party was always the Party with a capital P), though Jean had joined only that spring. They met at the headquarters of the British Communist Party in King Street, Covent Garden, in the underground room where student gatherings were held. Ralph was about to begin his final year reading history at Oxford and Jean to start a history degree at St Andrews in Scotland. As the universities were five hundred miles apart, they relied on letters; telephoning, in those days of public call boxes, was more difficult. A few months later they got engaged.

When I met Raphael in the mid 1980s, he told me about his first fiance; she came to our wedding party and we are still in touch. Raphael was a familiar figure by then on the British Left, with a reputation as a radical historian and as the founder of the History Workshop movement, but I knew little about his past. He was in the middle of writing a series of articles for New Left Review reflecting on his youth and on the lost world of the British Communist Party. He gave me copies. All lovers share their histories but this was too much information too soon. I merely skimmed the pieces, concentrating on the personal bits. Im glad you didnt know me then, he would say. His early incarnation as Ralph, for whom politics was everything, made him squirm. Raphael had wanted to write a further article based on his letters to Jean, which she had kept. In due course, like a good comrade, she sent them, but he never got any further than a few sketchy notes.

I found Raphaels letters to Jean and his notes when I was sorting through the mounds of files, papers, books and materials in our Spitalfields home after his death. I was hoping to establish an archive of his work but I also wanted to clear his study, turn it into a sitting room, and not have to confront his absence every time I walked into the house. I put the letters to one side. I could not bring myself to read them. Not, Im afraid, because of any qualms I had about intruding on other peoples privacy. I expected these letters to be largely concerned with Party matters. But Raphael and I had also conducted our courtship by correspondence from different cities. In the throes of grief I was not in the mood for parallels or comparisons, no matter how dry and distant.

Fast-forward another twenty years, and, with this memoir in mind, I encounter the letters again as I go through the boxes I still have. These boxes have travelled with me in my widowhood from London to Newcastle and on to Oxford. Jean is living down the road and we meet up for a walk in the University Parks. She comes down hard on her earlier political commitments: We were children then, children, she insists. And I wonder to myself how Raphael would have talked or written of his past had he too lived to be a spry octogenarian.

In his notes for his articles in the 1980s, Raphael was looking for evidence of what he called, in Marxs terms, the species-being of a young Communist in the Britain of the 1950s, self-consciously recognizing what he shared with other members of the Party. Ralph was to be an example of a psyche shaped by some thirteen years of CP formation (Raphael deemed himself a Communist at the age of eight). There was little to recommend them as letters, he thought that is, as literary artefacts fashioned for a reader. They are emotionally monotonous and censorious. They made him wince. The humour, he wrote, strikes me as leaden; the letters have no eloquence, no guile, no surprise. Although he conceded that the person who wrote them seems to have a low view of his abilities and to be without personal conceit, this he felt was a trick of self-presentation (so some guile after all?).

It is true that the letters are mostly digests or reports of the sort that might appeal only to the historian of political movements or to the cognoscenti; much is doctrinaire. Here was the young ideologue analysing the news from the Partys British mouthpiece, the Daily Worker, scrawling sixteen or seventeen pages every couple of days twenty-three on the resignation of Clement Attlee, the British prime minister, a letter which nonetheless ends in haste. Here are the minutiae of branch meetings, the sagas of days and nights spent recruiting I hammered away at him, Ralph writes of one hapless soul he was working on the detail of campaigns, study groups, rallies and demonstrations, canvassing for signatures and organizing rallies or demonstrations. Much is couched in sectarian Party terms, and the pedagogic strain is indeed, as Raphael laments in his notes, absolutely consistent. Young Ralph had spent two of his three years at Oxford on work for the Party. Now he was determined to get a first-class degree, since it behoved Party members to prove their intellectual worth. He becomes Jeans long-distance tutor, sending her reading lists to counter the insularity of the history degrees they both have to endure. He offers all manner of political advice. The tone of his letters seems immeasurably fuddy-duddy in these days before the idea of a youth culture hit Britain. Ralph is a twenty-year-old going on forty.

So why do I find Ralph so appealing? He seems to me no more lacking in self-knowledge than most self-absorbed young men. I find him funny too. My letters to you all seem to be the accurate reflection of the Complete Bore, Ralph confesses. This has been worrying me quite a lot recently. Despite their conscious intentions, the letters are shot through with longing they are love letters, from someone all too obviously in the grip of intense passions which cannot be controlled. Though headed only Thursday or Sunday, their sequence can be as easily dated by the escalating endearments as by the unfolding events in the Communist world. A first letter in autumn 1955 begins Dear Jean and is signed, somewhat ambiguously, many friendly and other fraternal greetings, Ralph Samuel. Gradually the address warms to darling or sweetheart, with cheerio and even love by way of farewell. The last few culminate in dearest sweetheart and all my love.

Ralph is in love and his world is gloriously transfigured. He wants to talk to everyone about Jean, to learn everything Scottish, and he drags Scotland into every conversation at the drop of a hat (or a tam-o-shanter). He even affects a sentimental Scottish accent, using wee in the letters. She is perfect, radiant, the ideal object of his affections. He is beset by fears before their next meeting. What if she goes under a bus? He bombards her with letters and she tries to slow him down. When Jean is overwhelmed, he vows, I promise to write less, and to stay extrovert. Much in the letters evokes a familiar courtship dance: advance, retreat, advance, retreat. Surely dont write to me of love has been the womans defensive cry throughout the ages as she feels herself besieged?

Next page