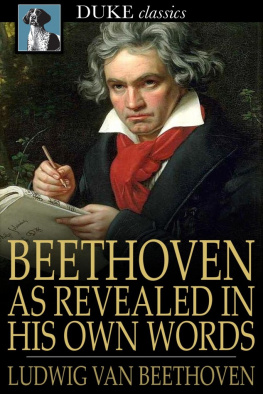

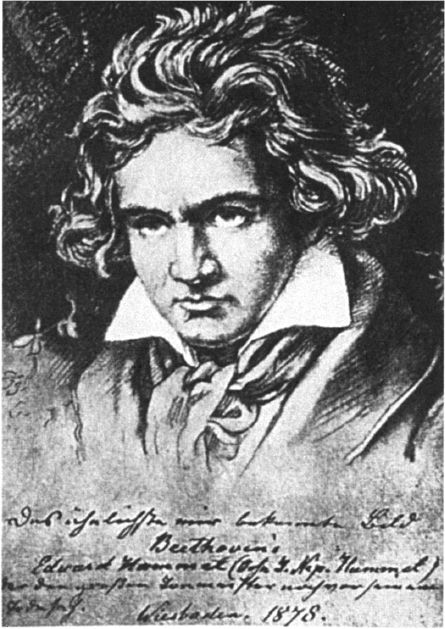

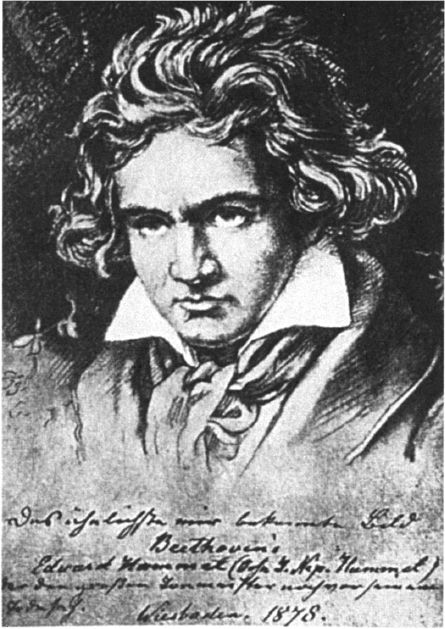

Beethoven at the age of forty-nine (1819)

From a portrait by Josef Stieler

BEETHOVENS

LETTERS

WITH EXPLANATORY NOTES

BY

DR. A. C. KALISCHER

TRANSLATED WITH PREFACE BY

J. S. SHEDLOCK, B.A.

SELECTED AND EDITED BY

A. EAGLEFIELD-HULL, Mus. Doc. (OXON.)

ILLUSTRATED

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

NEW YORK

This Dover edition, first published in 1972, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., London & Toronto (in New York by E. P. Dutton & Co.) , in 1926. The present edition is published by special arrangement with J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., London.

international Standard Book Number: 0-486-22769-3

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-159687

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc.

31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

MR. SHEDLOCKS English translation of Dr. Kalischers Complete Collection of Beethovens Letters has now unfortunately been out of print for many years. I therefore willingly accepted the publishers proposal for a handier and less expensive form of this work, to be brought about by a selection of those letters which, bearing more particularly on the music of Beethoven or more directly on his character, are of great interest to the general lover of music. Having first sought the approval of Mr. Shedlocks executrix, Mrs. Manning, I immediately availed myself of some corrections which Mr. Shedlock sent me some years ago for another work.

The present selection in one volume is a book for the general reader, rather than for the musical researcher and historian. I feel sure that every music-lover who has not Dr. Kalischers German collection (1220 letters) will be thankful for this condensation, which contains all that is most valuable as a search-light on the music and the character of Beethoven.

A. EAGLEFIELD-HULL.

PREFACE

THIS appears to be the special task of biography: to present the man in relation to his times, and to show how far as a whole they are opposed to him, in how far they are favourable to him, and how, if he be an artist, poet, or writer, he reflects them outwardly. Thus wrote Goethe in his Wahrheit und Dichtung, and, as regards Beethoven, his letters offer a unique biography, for studying the man in relation to his times, while such works as the Eroica and Choral symphonies certainly reflect them outwardly. We also see clearly from his letters how deeply he was affected by the times. He did not suddenly decide to write a work and dedicate it to Napoleon, for that was his original intention with respect to the Eroica, nor did he suddenly think the Schiller Ode to Joy would be a fine poem to set to music; but the one work was the outcome of strong sympathy with the man whom he thought was about to establish a republican millennium, the other of ardent desire for peace and goodwill to reign upon earth. Reichardt tells us of the ideals after which men were aiming at the end of the eighteenth century. The victories of the republican armies specially impressed Beethoven soon after his arrival in Vienna, for his native country suffered thereby, while the Ode to Joy of Schiller, though the setting was a late one, occupied his thoughts from a very early period. Of the horrors of war he had personal experience. In 1801 we find him taking part in a concert for the benefit of the wounded Austrian soldiers at the battle of Hainau; in 1805 Vienna was occupied by French troops, and again in 1809 the city of Vienna was bombarded and then occupied by Napoleon. The events of 1805 were unfavourable to the success of his opera Fidelio, while those of 1809 greatly worried him. What a disturbing wild life all around me, nothing but drums, cannons, men, misery of all sorts. So he writes in a graphic letter to his publishers, Breitkopf and Hrtel (26 July, 1809). How far these and other events may have interfered with his art-creations is difficult to determine; but the great works which he produced were surely in part owing to the excitement of those times. Had Beethoven lived a quiet, peaceful life, such as that of Haydn at Esterhz, it is very doubtful whether we should now possess the Eroica, C minor, and the later Symphonies.

Much could be said about Beethoven and the times in which he lived, and many quotations could be given from the Letters, but for the moment we wish to say something about them as showing what kind of a man he was. In these Letters we get at the very heart of the composer, and his thoughts and feelings are expressed in strong characteristic terms, yet quite naturally. From their general character one is convinced that Beethoven had absolutely no thought of their ever being published. For the most part, they are anything but models of style, yet, and not unfrequently, there are sentences which seem, as it were, inspired. A few have been often quoted. Here is one less familiar. In he writes to his friend and helper, Nanette Streicher, who is at Baden: If you go to the old ruins, think that Beethoven lingered there; if you wander through the mysterious fir-forests, think it was there Beethoven often poetised, or, as it is called, composed.

By reading Berliozs Mmoires one gets a very good idea both of the man and the musician; of his likes and dislikes, of his excitability, and at times of his despondency, of his high ideals, of his outspokenness, and of his art career generally. Berlioz had a powerful pen, and drew a strong picture of himself. Yet there is a literary polish about the whole thing: while writing, Berlioz had the public in mind. Therein lies the difference between his Mmoires and the Letters of Beethoven. Setting aside the dedication letter to the Prince Elector of Cologne, in which his father no doubt had the larger share, the rest of the correspondence gives a natural picture of the man. Many, nay, probably most, were written in a great hurry; in der Eile was the composers usual ending to his letters, and of haste the letters bear many traces: the same words are constantly repeated; the structure of the sentences is frequently very loose, and at times it is, indeed, hard to find out what he meant. For punctuation he cared little. With him, the comma did duty for comma, semicolon, also full stop. At times, indeed, he hurries on to a fresh sentence without any kind of stop, and does not even trouble to begin a new one with a capital letter. Nouns, which in German always begin with a capital, seldom have it, and on the other hand, words not needing one have one. Again, there is constant confusion with the pronouns sie, ihr and ihnen, which seldom have a capital initial letter when such is required. Another proof of haste will be found in the spelling of proper names; very few of them are correct. They have been left in the Letters as he wrote them. It is a characteristic feature which I felt ought to be represented. It is curious to note that in a letter to Schindler, he says: But you are a bad speller And, finally, hurry is shown in his handwriting, which often puzzled even Jahn, Schindler, Nohl and others who had seen and studied very many of the composers autograph letters. In informing Neate of the conditions on which he would accept a proposal of the Philharmonic Society, he states that he got someone to write the letter, so that it might be easier to read. And in a letter to Streicher he describes how one day at the post office he handed in a letter, and was asked by the official whither it was to be sent. And he adds that he himself, like his writing, is often misunderstood.

Next page