SANFORD FRIEDMAN (19282010) was born in New York City. After graduating from the Horace Mann School and the Carnegie Institute of Technology, he was stationed as a military police officer in Korea, earning a Bronze Star. He began his career as a playwright and theater producer, and was later a writing instructor at Juilliard and SAGE (Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders). Ocean, a chapter from Friedmans first novel, Totempole, was serialized in Partisan Review in 1964 and won second prize in the 1965 O. Henry Awards. Totempole (1965; available as an NYRB Classic) was followed by the novels A Haunted Woman (1968), Still Life (1975), and Rip Van Winkle (1980). At the time of his death, Friedman left behind the unpublished manuscript for Conversations with Beethoven.

RICHARD HOWARD is the author of seventeen volumes of poetry and has published more than one hundred fifty translations from the French, including, for NYRB, Marc Fumarolis When the World Spoke French, Balzacs Unknown Masterpiece, and Maupassants Alien Hearts. He has received a National Book Award for his translation of Les Fleurs du Mal and a Pulitzer Prize for Untitled Subjects, a collection of poetry. His most recent book of poems, inspired by his own schooling in Ohio, is A Progressive Education (2014).

CONVERSATIONS WITH BEETHOVEN

A Novel

SANFORD FRIEDMAN

Introduction by

RICHARD HOWARD

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 2014 by Sanford Friedman

Introduction copyright 2014 by Richard Howard

All rights reserved.

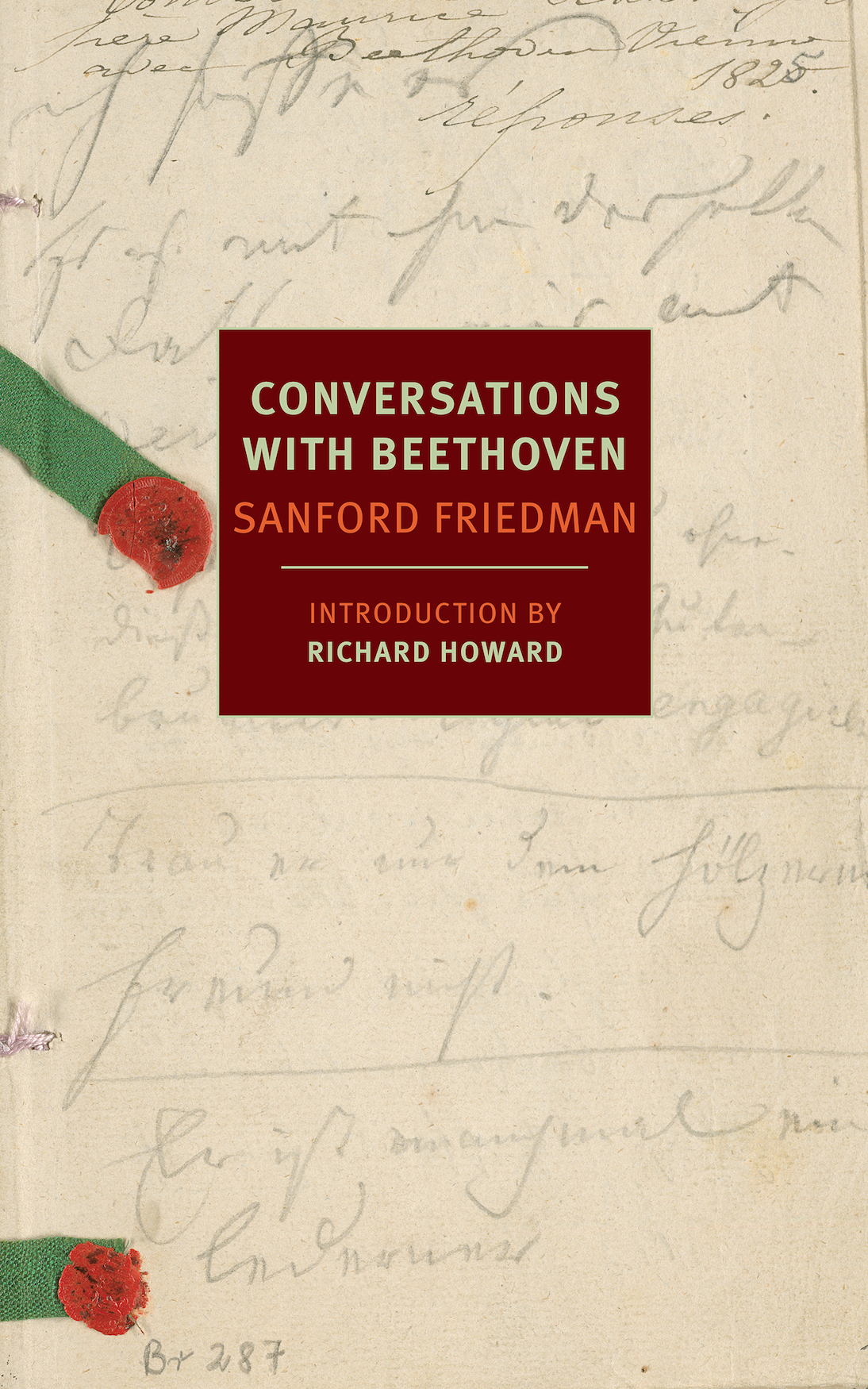

Cover image: Pages from a conversation book belonging to Ludwig van Beethoven, dated September 9, 1825; BeethovenHaus Bonn, collection of H. C. Bodmer

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Friedman, Sanford, 19282010.

Conversations with Beethoven / by Sanford Friedman ; introduction by Richard Howard.

1 online resource. (New York Review Books classics)

Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.

ISBN 978-1-59017-788-4 ISBN 978-1-59017-762-4 (alk. paper)

1. Beethoven, Ludwig van, 17701827Fiction. 2. ComposersGermanyFiction. I. Title.

PS3556.R564

813'.54dc23 2014018738

2014013610

ISBN 978-1-59017-788-4

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

From the Sidelines

B ETWEEN graduating from Horace Mann and earning a BFA from Carnegie Tech, Sanford Friedman wrote seven full-length plays, the first of which was produced when he was nineteen at the University Playhouse on Cape Cod. The subsequent six were never produced nor even published, though I recall reading an arresting melodrama about John Brown which Friedman had written in his early twenties and set great store by to the end of his life.

After his discharge in 1953 from the armyhe served as a military policeman in Korea and was awarded a Bronze StarFriedman and two rather spooky associates leased and renovated Carnegie Hall Playhouse and for two seasons produced plays by, among others, Samuel Beckett, Eugne Ionesco, and Brendan Behan. Revealed as a possibly profitable enterprise, the Playhouse was whisked away from these young, helplessly highbrow producers and, after a questionable stint as Carnegie Hall Cinema, eventually assumed its present, much glamorized guise of Zankel Hall, one of whose occasional highbrow vestiges was to be the Susan Sontag memorial concert.

It was not, however, until 1965 that Friedman published his first novel, Totempole, which was a considerable success, even thoughor perhaps becauseit was the first American fiction whose central character was a sensitive M.P., both Jewish and homosexual. Totempole was followed in 1968 by A Haunted Woman, the romance of a withering but resourceful actress remarkably like Mrs. Jackson Pollock. Then, in 1975, Friedman produced a curiously disparate pair of what his (new) publisher rather cautiously called short novels: the cover says Still Life, but inside we must contend with Life Blood as well as Still Lifehow short can that be? And then, in 1980, yet another publisher presented another (singular) Friedman novel, Rip Van Winkle, which turns out to be the recuperation of an American legend which makes that aspiring designation mean what it actually prescribes: this legend had better be read.

Thereupon follows an extended silence of thirty years until Sanford Friedman voicelessly dies (of a heart attack inside his own front door) in the spring of 2010but no, I am surely referring to the deliberately stridulent mutism that followed the completion, late in the 80s, of this writers last (and breathlessly original) novel, remote from any earlier mannerisms and in fact suggestive of the alien designs of Thomas Mann or even W.G. Sebald. The frustrated efforts, over the next twenty years, of this now middle-aged New Yorker to find a publisher for his most ambitious and perhaps finest work were accompanied by a growing rage against the disappointing silencetimidity? repugnance? indifference?to which it appeared to be condemned.

But this too is a deception: if The Author proposes his withdrawal, Literature (eventually) presents his triumph. I believe, deep down, that Sanford Friedman would have been pleased, or at least satisfied, that what he thought of not as his last but rather latest book would, finally, be out in the world with its predecessors. I lived with Sanford Friedman for most of the time (nineteen years) during which his books were written; I lived against him in the years after. I had many opportunities to observe this remarkable writer and few enough to comfort him, but at least I can point out the wonderful inventiveness of the text of Conversations with Beethoven, starting with the title. As most of us know, Beethoven, in the last part of his life, had gone deaf, and the only way anyone could converse with the elderly genius was by scribbling a message, however intimate or formal, in a notebook. Many of such notebooks still survive, and of course the remarkable thing about the conversations thus preserved is that the talk of everyone except the frequently volatile composer is recorded. Beethoven would read the texts and respond aloud (except when he wished to keep his own responses private; at these times the composer himself would write them in another notebook to be shared with only the intended receiver). For the most part, however, the deaf man seems to have been so urgently committed to what he wanted to say, what he wanted done (or not done), that having nothing to go by but the texts of others, we must imagine, sometimes rather sketchily, what the great mans responses may have been. Though of course Beethoven himself could and did write formal (or informal) letters to be mailed or manually delivered by his own servants...

The wonder of Conversations with Beethoven, then, is that each of us must determine its import according to our reading of the words, as Friedman has imagined them, of those who within its pages dare to address the aging, irritable, and eventually hospitalized Maestroespecially his five querulous doctors, his surviving brothers, and his beloved nephew Karl (who has, to his uncles horror and outrage, ventured to become an officer in the Austrian Royal Army), as well as the boys hated mother (she closes the conversations with an eight-page letter to her son describing Uncle Ludwigs funeral), and a troop of terrorized admirers and musicians (including Franz Schubert) who are more often than not misrecognized by the dying composer, not to mention any number of greedy noblemen eager to be distinguished by the Maestros dedication of whatever scrap of his immortal music remains unspoken for.