Table of Contents

Benita Eisler

Chopins Funeral

Benita Eisler is the author of OKeeffe and Stieglitz: An American Romance and Byron: Child of Passion, Fool of Fame. She lives in New York City.

ALSO BY BENITA EISLER

OKeeffe and Stieglitz: An American Romance

Byron: Child of Passion, Fool of Fame

PART I

Departures

ONE

Lacrymosa dies illa: What weeping on that day

On a sparkling Paris morning, Tuesday, October 30, 1849, crowds poured into the square in front of the Church of the Madeleine. The occasion was the funeral of Frdric Chopin, and for it, the entire facade of the great neoclassical temple had been draped in swags of black velvet centered with a cartouche bearing the silver-embroidered initials FC.

Admission was by invitation only: Between three thousand and four thousand had received the black-bordered cards. Observing the square with its crush of carriages, the liveried grooms and sleek horses, the throngs converging on the porch, Hector Berlioz reported that the whole of artistic and aristocratic Paris was there. But another who surveyed the crowd, the music critic for the Times of London, suspected that of the four thousand who filled the pews, a large number had been admitted just before noon, strangers to the dead man, mere bystanders even, many of whom, perhaps, had never heard of him.

If death is a mirror of life, Chopins funeral reflected all the disjunctions of his brief existence. The most private of artists, his genius was mourned in a public event worthy of a head of state. Canonized as angelic, a Shelleyan poet of the keyboard, Chopin seemed to personify romanticism, and before he was buried, its myths had already embalmed him: a short and tragic life; an heroic role as Polish patriot and exile; doomed lover of the centurys most notorious woman; and finally, his death from consumption, that killer of youth, beauty, genius, and of courtesans foolish enough to fall in love.

In reality, he was the least romantic of artists. While the generation that had come of age just before his own in France, including the Olympian Victor Hugo, had defined romanticism as a holy war of the moderns (themselves) against the ancients (their literary elders), setting off riots in theaters to make their point, Chopin clung to the past. His musical touchstones were Haydn, Mozart but especially Bach. He harbored doubts about Beethovens lapses of taste, was incurious about the music of Schubert, and generally contemptuous of his other contemporaries: Schumann, Berlioz, and Liszt, towards whom his feelings were further tangled by rivalrous friendship. In art, he preferred the marmoreal neoclassicism of Ingres and his followers to the radical inventions in color and form of his friend Delacroix. Socially and politically, he was still more conservative.

The same aristocratic circles that had embraced Chopin the child prodigy in Warsaw were waiting to welcome the twenty-one-year-old sensation of Paris. Chopin arrived in France in 1831. One year before, revolution had replaced the Bourbon Restoration with the Orleanists swept in by Louis Philippe and his July monarchy. It was still a world of fixed hierarchies: of titles, birth, and breeding, buoyed by a flood tide of fresh money coined by the financiers and industrialists whose entertainments outshone the Sun King in splendor, if not in style. Chopin made some friends among the professional middle classa less grand banker or diplomat, a few fellow musicians. He had a horror of the People as a force of upheaval or even change (which he dreaded in any form), and he was suspicious of those who championed their cause. He was appalled by that quintessentially romantic belief, whose most ardent proponent was George Sand, that art must serve the cause of social justiceor, indeed, any other cause except itself.

Like many who have thrived as exceptions, propelled by talent from modest origins to a place among the privileged, Chopin was repelled by marginality: by poor Poles, by Jews, by the ill-dressed and ill-mannered, by coarseness or slovenliness, in art or life.

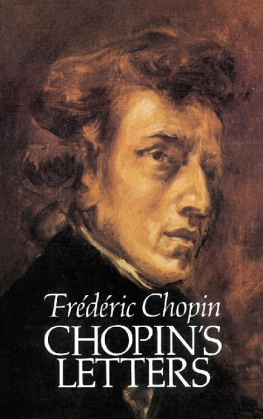

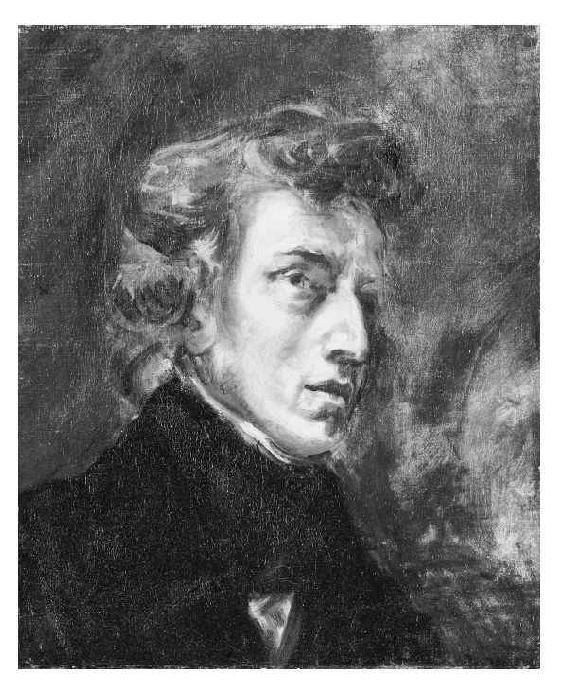

Most likenesses of the composer suggest that he was far from handsome. He had pale, colorless hair, a thin, hooked nose, a pursey mouth, and rabbity, lashless eyes. In these images, Chopin bears only a glancing resemblance to his famous portrait by Delacroixthe portrait of romantic genius itself, with his tousled chestnut mane and burning inward gaze. Chopins famous dandyism, then, must be understood as another labor of creation, like his music an imperious quest for perfection. The dandy enlists distinctionin dress, speech, mannersalong with distance, to create a masterpiece: himself.

What appeared to manythen and nowas the snobbery of a provincial, self-invented aristocrat and aesthete, had deeper sources. Chopin needed the reassurance that a fixed social order provides. Dependent and childlike in many ways, he clung to the security of protective institutionsthe monarchy, the Church, and the familywhich defined themselves proudly as patriarchal, stern but loving fathers keeping watch over children, dedicated to exalting an ideal past and to keeping present chaos at bay.

Two years and only two public concerts after his arrival in Paris, Chopin ranked among those few artists who moved in every circle that counted. Ignoring protocol, older, established musicians called upon him. He was a fixture at the grandest houses, where, arriving in his own carriage, he was welcomed as a lionized guest who never failed to charm and amuse; if he could be prevailed upon to perform, he hypnotized every listener. The musically knowledgeable drew close to the piano to study the wizardry of his technique and his famous inventions in fingering, third finger crossing the fourth, that made his impossibly difficult compositions appear effortless. Fellow exiles heard laments for a homeland in the languorous rubato of the mazurkas, with their heart-catching drop from major to minor keys, but the mood of elegy was as often shattered by discordant salvos of unleashed rage. Even those guests whose attendance was simply an occasion to wear the new diamonds, to remark casually at the bourse that the reception last evening at Baron Jamess had been more than usually delightful, stayed well past midnight, straining to hear the final note, when the pianist, pale and exhausted, rose wearily to take his bow. It was uncanny how Chopins music spoke so intimately to their most private, long-buried thoughts and memories, evoking childhood happiness and lost love; innocent, nobler selves trampled by the harsh rules of life.

Seventeen years later, he died, destitute, in an apartment paid for by friends at the most fashionable address in the most expensive quarter of Paris.

Now, at the funeral, emissaries from the world of music were outnumbered by mourners from the ranks of the rich and titled. The Polish migr aristocracy and its French counterpart among the old noblesse were in turn outshone by new money: bankers and speculators whose wives and daughters had also been among Chopins pupils. Certain of the fashionable, one reporter noted, appeared indecorously attired in brilliant colors, glittering with jewels.