Paul Kildea

CHOPINS PIANO

A Journey Through Romanticism

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Copyright Paul Kildea, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover: Bridgeman Images/Mary Evans Picture Library

ISBN: 978-0-241-18795-1

List of Illustrations

Excerpt from T. S. Eliot, Prufock and Other Observations, reproduced by kind permission of Faber & Faber Ltd

Excerpts from George Sand, trans. Dan Hofstadter, The Story of my Life, reproduced by kind permission of The Folio Society

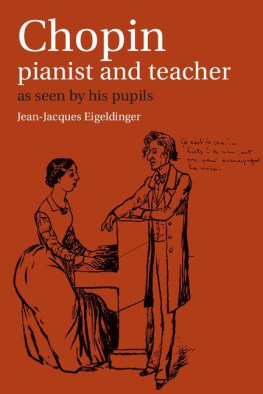

Excerpts from Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger, Chopin: Pianist and Teacher, As Seen by his Pupils, trans. Naomi Shohet, Krysia Osotowicz, Roy Howat, reproduced by kind permission of Cambridge University Press

Preface

I began thinking about the history of pianism as a doctoral student, working under the supervision of the brilliant social and economic historian Cyril Ehrlich. In the mid-1970s Cyril had written a terrific book, The Piano: A History, an exploration of the impact of the pianoforte on society, industry and entertainment, from Mozarts time onwards, which he had revised and republished two years before I came to work with him. His focus was not so much on how these instruments were played, or how knowledge of nineteenth-century pianos would add ballast to historically informed performance, a movement then in full swing. As a fine amateur pianist, who had educated himself musically on the family piano and his fathers 78s, Cyril was instead intrigued by the social phenomenon the instrument represented.

Chopins Piano: A Journey Through Romanticism is the opposite of Cyrils book; its thread is a single instrument, not an entire industry, one made in Palma in the 1830s and which had a most eventful life. When initially I began tracing the history of the piano who owned it, what was composed and played on it, what it came to mean to different people over time I realized that to do the subject justice I also had to write about how pianism changed following Chopins encounter with the instrument, how audiences, society, taste and programming changed alongside it, and how musical Romanticism forged such interesting and unexpected paths during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as different performing styles and political and cultural ideologies staked their claim. Many other ideas and historical events were subsequently caught up in the narrative. In twenty-four chapters divided into two parts (a nod to the twenty-four pieces, originally published in two books, that constitute the astonishing collection Chopin finished on this instrument), I use the history of the piano to write about the arc of musical Romanticism, including our complex relationship with it today.

Cyril and I talked about many things in marathon supervisions involving beer and frankfurters, though I cannot recall ever discussing the musical Salad Days, which opened in London in 1954 just as he was writing his PhD thesis (on cotton marketing in Uganda), and which enjoyed a record-breaking run of over 2,200 performances. It tells the story of an old piano that has an almost intoxicating effect on anyone who hears it played. At one point the instrument vanishes, which causes great consternation among those who have come to rely on its hypnotic properties, and which prompts the full company to sing Were Looking for a Piano. This is more or less what I get up to in this book.

Apart from the conversations I had with Cyril all those years ago, for which I remain ever grateful, many people were generous with their expertise, friendship and hospitality as I researched and wrote this book. Those involved in the construction, restoration or collecting of pianos and who were of immense help include Jean-Claude Battault (Muse de la Musique, Paris); Alec Cobbe and Alison Hoskyns (The Cobbe Collection); Olivier Fadini; Uli Gerhartz (Steinway & Sons); Solomon Haileselassie (Coolidge Auditorium, the Library of Congress); Chris Maene and his team, including Tine Mannaerts and Wolf Leye; Donald Manildi (International Piano Archives at Maryland); and Christophe Nebout (Pianos Nebout).

Museums and archives were a rich resource and I would like to thank Christopher Hartten and his colleagues in particular Cait Miller and Walter Zvonchenko at the Performing Arts Reading Room of the Library of Congress, Washington D.C., who steered me through the Landowska/Restout collection; Maciej Janicki and Grayna Michniewicz (Muzeum Fryderyka Chopina); Jayson Dobney and Ken Moore (Metropolitan Museum, New York City), along with a very helpful security guard with a masters degree in guitar, whose name I stupidly failed to ask; Martin Elste (Musikinstrumenten-Museum, Berlin); Lilia Franqui (Probate Court, Coral Gables); Jochende Schwarz (Felicia Blumenthal Music Center in Tel Aviv); and Grard Tardif (LAssociation pour la Sauvegarde de lAuditorium de Wanda Landowska).

A number of musicians had fascinating and diverse thoughts about Chopin and pianism, including two old friends, Dejan Lazic and Cedric Tiberghien. Jeremy Filsell (Artist in Residence at Washington National Cathedral and Music Director of Washingtons Church of the Epiphany) was generous with his time and his ideas on improvisation. Michael Black and Simon Kenway, two outstanding musicians, were, as ever, stimulating friends and generous hosts, as was Simons mother Carmel. Genevieve Lacey had inspiring thoughts on just about everything. Christopher D. Lewis had some great tales to tell about Landowska and Pleyel, and kindly sent my way a number of photographs I had not seen before. Linda Kouvaras not only plays the piano beautifully but talks about it and music with equal skill. Helen Moody gave me late-night help with homework. Skip Semp is a passionate and erudite Wanda Landowska advocate and I greatly benefited from my time with him. Peter Roennfeldt shared his knowledge of early pianos and generously allowed me to sit in on a trio rehearsal with his fellow musicians Margaret Connolly and Daniel Curro. Jill Stoll, apart from being a really fine pianist, told me about a viola in Vienna. Finn Downie Dear and Laurence Matheson play beautifully and had interesting things to say about Chopin, as did Chiyan Wong about Busoni. Keith Radford introduced the adolescent me to Szymanowski, though never managed to convince me then of Chopins brilliance (my fault entirely). Anita Lasker-Wallfisch was kind enough to revisit in my company the harrowing events of 193945.

Scholars who generously shared their expertise include Malcolm Gillies, who also read the book in manuscript and had his usual array of whip-smart comments and criticisms; the superb critic and sideways-thinking John Allison; the continually inspiring Jennifer Doctor; Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger (whose treasure-trove book, edited by the creative and original pianist and musicologist Roy Howat whom I also thank was an invaluable resource); and Alain Koehler, Jennifer Bailey, Mackenzie Pierce and Caroline Gill, all of whom had valuable comments to make. I am grateful for the support of Professor Barry Conyngham and Professor Gary McPherson at the University of Melbourne, where I am an Honorary Principal Fellow at the Conservatorium of Music. Carla Shapreau, who is currently working on what will become the standard text on the looting of musical instruments and collections during the Second World War, was extremely generous with her thoughts and time, as was Willem de Vries, whose research into Nazi looting was both pioneering and invaluable. Teri Noel Towe shared his knowledge of Landowska and memories of Denise Restout.