Jan Marisse Huizing

Frdric Chopin

The Etudes

History. Performance Practice. Interpretation

Translated from the German by Matthias Mller

In remembrance of Jan Ekier (1913-2014)

SDP 124

ISBN 978-3-7957-8549-9

2015 Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG, Mainz

All rights reserved

www.schott-music.com

www.schott-buch.de

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Cover: Stefan Pegatzky

Preface

Alfred Cortot [on the Chopin etudes]:

Bold undertakings to which the musician without virtuosity is just as unable to find access as the virtuoso without musicality.

Von Lewinski, II, p. 1.

The first thing a book about Chopins Etudes brings to mind would be something in the way of a piano methodology; a personal, methodic approach to the (technical) challenges of these works. This is however not the primary focus of my book. Instead it deals with another, no less intriguing aspect: the Etudes in a historical perspective. While there are a number of publications that concern themselves with specific methods of technically coming to grips with the Etudes, these masterpieces have in the course of the history of piano playing rarely been examined from a historical perspective. However, the growing interest for historical performance practice need not limit itself to pre-Romantic music; it certainly makes sense to apply this approach also to the Chopin Etudes that have been of key importance for the development of piano playing.

Chopin began work on his Etudes Op. 10 while still in Poland when he was not yet twenty, followed these up in Paris with the twelve Etudes Op. 25, finally writing three smaller Etudes a few years later.

When his Op. 10 was published in 1833 it caused a veritable sensation among his contemporaries, and together with his Op. 25 which was published in 1837 it was regarded as the summit of the pianistic parnassus. This is still the case today. Essential for acquiring a virtuoso piano technique, Chopins Etudes stand alone in that here technique is wedded in an unparalleled way to a wealth of musical ideas.

This book sheds light on a variety of aspects that are connected to historical performance practice: keys, manners of playing, tempo / character and metronome indications, pedaling and variants are put into perspective with regard to Chopins piano writing and the instruments he used. Attention is also given to a number of Urtext and historical editions as well as to the way the musical image of a work has changed over time. The book concludes with an overview of the many recordings of these Etudes that have been made over the years and an appendix presenting the different systems of piano action in the instruments used in Chopins time and after.

This is also the place to thank those who have helped me in writing this book. First and foremost my heartfelt thanks go to the eminent Polish pianist and scholar Jan Ekier with whom I had the privilege of studying in Warsaw in the 1960s and who shared his great love for and knowledge of Chopins works with me, which meant a great deal to me. Moreover, Ekier encouraged me in many conversations to write this book. Sadly, in August 2014, a few weeks before his 101 birthday, he passed away.

Also important was the exchange of ideas with the Swiss Chopin expert Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger, who graciously gave me permission to quote comments of Chopins pupils that he collected in his book Chopin: pianist and teacher as seen by his pupils.

After my book was published in 1996 in Dutch by de Toorts in Haarlem, my friend and colleague the German pianist Detlef Kraus, who suddenly passed away in 2008, offered to translate it into German. This resulted in a revised edition published by Schott in 2009, and here I am very grateful to Paul Badura-Skoda, pianist and editor of the Wiener Urtext edition of the Chopin etudes, for letting me avail myself of his critical eye.

And now this English version has given me the opportunity to make some further amendments and include additional material, in particular in chapters 2, 4, 5, 7 and 8.

My special thanks go to translator and musician Matthias Mller for undertaking the task of creating the English text for this ebook which led to an intensive and inspiring collaboration.

In addition I would like to thank the Bibliothque National in Paris for the permission to reproduce a number of facsimiles, and to Hanna Wrblewska-Straus, the former curator of the Chopin Institute Towarzystwo im. Fryderyka Chopina (TiFC) in Warsaw, who made it possible for me to study Chopins original manuscripts and provided photographic material. I also owe thanks to the sterreichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna for furnishing me with an important facsimile, as well as to the publishers Henle, Wiener Urtext, Breitkopf & Hrtel and Schott for their kind permission to reproduce examples taken from their editions.

Finally, I hope this book will shed some light on the musical contents and background of Chopins Etudes and contribute to arriving at inspired interpretations of these masterpieces.

Jan Marisse Huizing, The Hague, Autumn 2015.

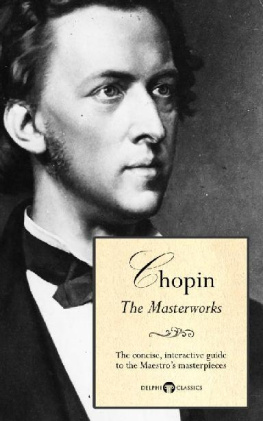

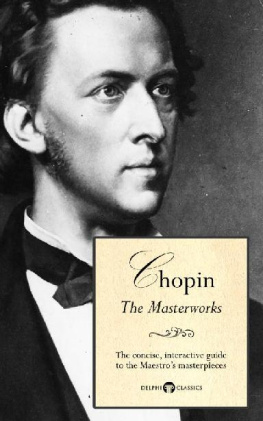

A portrait of Chopin in a rare lithograph. Drawing by Ccilie Brandt after a portrait by Vigneron (lithograph, by A. Kneisel, Leipzig; private collection). The portrait was made in 1833, the year the Etudes Op. 10 were published.

1 The piano etude in Chopins time

Robert Schumann [on Chopins Etudes Op. 25.]

But wherefore the descriptive words! They are all models of bold, indwelling, creative force, truly poetic creations. []

(Neue Zeitschift fr Musik, 22.12.1837). (Huneker, p. 99.)

When Chopin composed his Scarlattis sonatas he called them Essercizi as perhaps the most outstanding works of their kind.

During the Baroque period, but also for a great part of the style galant and the early classical period, the different strength of the fingers was particularly emphasized. In that time there was talk of good and bad fingers that should be used in the service of a specific articulation to be derived from the musical text. Good fingers for the good notes, as they were called, By contrast, on the new instrument, the fortepiano, which became very popular around the time of the Viennese classical period, it was not only possible to play in a nuanced way within extended passages but also within one chord. In addition, crescendo and diminuendo became important new means of expression.

These new developments were thus directly connected with a stylistic change. The transition from articulation to phrasing, differentiations within the dynamics and greater equalness in passage work were all means of expression in a new musical concept. Passage work, which in the Baroque period was frequently used in toccatas and preludes for instance, now served primarily to create connections between individual themes, as they appeared in the new forms of the time, for instance in the sonata and rondo form. In passage work, the necessary modulations could take place or a particular key could be reinforced for a longer period without the need for a new theme to appear.

In the light of this development technical problems naturally came to be related to the weakness of particular fingers. It was considered necessary to work on the strengths of the fingers in order to implement the new possibilities of expression in the piano music of the time.

Next page